By Zula Rabikowska

Zula Rabikowska is a Polish photographer based in London. Her project Ba Lan (meaning “Poland” in Vietnamese) offers an insight into the complexities and challenges of the lives of the Vietnamese community, Poland’s largest non-European migrant group.

Poland is a relatively mono-ethnic country, with one of the EU’s smallest populations of non-European residents. But an estimated 50,000-80,000 people of Vietnamese origin live there, and the community has been part of Polish society for several generations, something that even migration specialists are often surprised to learn.

I met more than 30 people of Vietnamese origin while working on the Ba Lan project. All the photos I took were influenced by conversations and stories that the participants of the project shared.

Inside a Vietnamese hairdressing salon in Wólka Kosowska.

Do Vu Dang Quang: “I was 12 when I arrived in Poland and I am turning 18 later this year. I feel Vietnamese, but adapting hasn’t always been straightforward. When we came to Poland, many things were new.

“My mum is a hairdresser and I love getting my hair dyed. There are many foreign children in my school and around 20% of them are from Vietnam. I don’t know where I see my future. I speak Polish in school and Vietnamese at home, because my parents find Polish harder. My half brother in the Czech Republic comes to visit us a lot in Poland, but we only speak English, because he doesn’t speak any Vietnamese.”

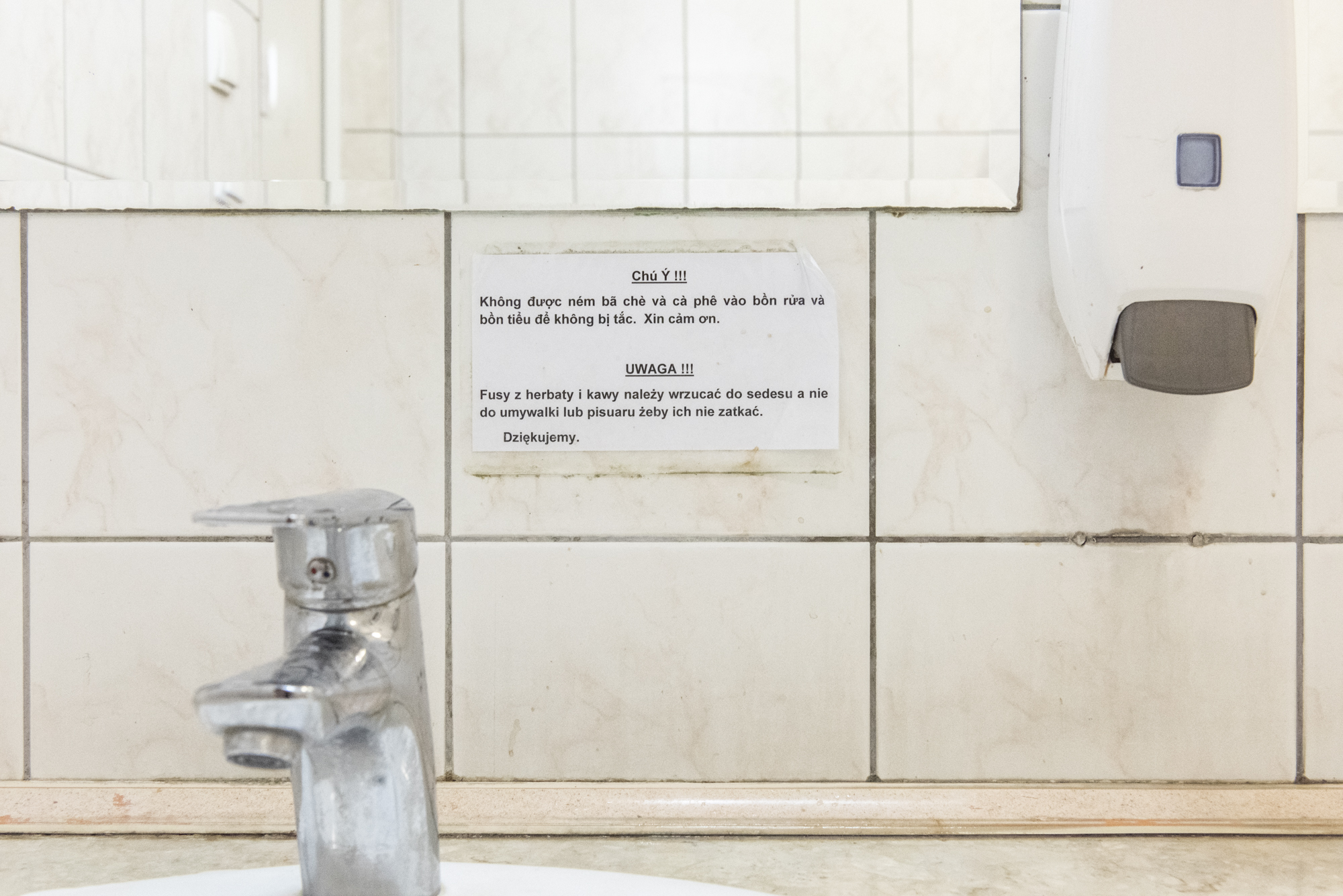

This photo is from Wólka Kosowska, one of the biggest wholesale trading areas in Eastern Europe and a workplace for many Vietnamese people living in Poland. The media in Poland are often reductive in their depiction of the Vietnamese community and use stereotypical photographs when presenting the situation. I wanted to highlight how Polish and Vietnamese cultures co-exist without replicating stereotypical images of market traders.

These two photos are from Bakalarska Market, a Warsaw district with some of the best Vietnamese restaurants and shops. Many of these places serve traditional Vietnamese food, incredible Vietnamese coffee, and more often than not Polish beer to go with it.

Ola Nguyen came to Poland with her family as a child, and attended school in Warsaw. She was brought up in a traditional Vietnamese household and learnt to cook at a young age whilst helping her mother out in the kitchen. In 2018 she won the Polish edition of MasterChef. She feels both Polish and Vietnamese. In Poland she uses the Polish name “Ola”, as it helps her establish a link with Polish society.

In the Ba Lan project I aim to show the opposite of the stereotypical image of the inaccessible Vietnamese community. Many Vietnamese community members volunteer every Sunday with a charity, Smile Warsaw, which distributes food and other donations to homeless people. The Vietnamese community also cook and distribute traditional Vietnamese food on a regular basis.

Nam: “I came to Poland about two years ago with my family, and I have been learning Polish ever since. I worked as a photographer and journalist, and I decided to leave Vietnam because of the restrictions on freedom of speech. As an artist, it was difficult for me to write and live there, so we came to Poland. I paint and translate poetry, and I can do this more freely in Poland.

“Every Sunday I volunteer for Smile Warsaw. I was the first Vietnamese person to volunteer in this group, and since then I have encouraged more Vietnamese members to join. I think it’s important to engage the Vietnamese community in Warsaw, as it can be difficult for them to integrate. I have many Polish and Vietnamese friends and I want to be a bridge between the Polish and Vietnamese communities.”

Traditional Vietnamese meal at Nam’s house with his family and friends.

Jade: “I am 13 years old and have been in Poland for two years. In Poland my chosen name is Hanna, but I like it when people call me Jade. I prefer speaking English to Polish or Vietnamese.

“Polish is a difficult language and there are no Vietnamese children in my class at school. When I started school, people were curious, but also friendly. At home I speak Polish, and I have Polish friends, but some of the kids are nasty and make horrible jokes about me and my family. I like to write poetry in English, and I love riding my skateboard to school. It gives me a sense of freedom.”

Bakalarska Market

“I am the only Vietnamese drag queen in Poland. I am half Korean and half Vietnamese, but my life is Poland. I have an IT business, and work as an actor, as well as a model. Most of my Vietnamese family are unaware of my drag queen performances. My wife is Polish and our son studies medicine. I keep my family life and my life as a drag queen separate. There are only around 30 drag queens in the country, and we already have a hard time being demonised by the government.

“There are two main stereotypical representations of a Vietnamese person in Poland. You are either depicted as the mafia, or a market trader at the old football stadium. There is no representation of artists or performers.“

There are two main pagodas outside Warsaw, which are a divisive factor within the Vietnamese community. Some people have rejected them for their alignment with the Vietnamese government and propaganda, whereas others choose to attend for worship and cultural reasons.

Thuy’s mother came to Poland on a student exchange in the 1970s, and used to teach Polish back in Vietnam. She now has a PhD in Polish literature. At home, Thuy’s family speaks Vietnamese and Polish. Her parents maintain many traditional Vietnamese customs. They still have an altar for her grandparents who passed away, and her mother prepares monthly offerings in their memory.

Thuy’s passion is making cakes, something which she now does for a living. Most of her friends are Polish, and as a child she used to go to Britain and the United States to learn English. She married a Polish man, and they have a son, Milan, with whom she speak Polish and Vietnamese. She feels split between Polish and Vietnamese cultures, and sometimes feels that her Vietnamese is not good enough, so she is thinking about taking private lessons.

Traditional Vietnamese altar in Thuy’s parents’ house.

Traditional Vietnamese altar in Thuy’s parents’ house.

This photo was taken in the tunnel outside the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw. The name of the shop translates as “Oriental World”. Most of the participants I spoke to noted their frustration at being exoticised, or seen as “Asian”, or even worse, as “Oriental”. Such adjectives have become normalised in society, and this shop is an example of this tendency.

“I came to Poland four years ago on my own. I was 18 years old at the time. I decided to leave my family in Vietnam and come to Poland to study. It was difficult, and there was a time when I was in Poland illegally without realising it. I was waiting for the final decision from the foreigners’ office, and ended up being deported back to Vietnam.

“The whole experience was traumatic. I stayed back in Vietnam for four months before getting my papers in order and being able to return to Poland, where I want to live. My family back home was unsupportive of my decision, and made unpleasant comments about my return.

“I am still learning Polish, and I am part of an English-speaking Vietnamese community and of a larger international expat group in Warsaw. I came to Poland because it’s much easier to get a visa here than other EU countries, and many companies in Vietnam recommend Poland as a work destination. I see myself as a Vietnamese person living in Poland, but I really want to be part of Polish society.”

Vietnamese graves in the Warsaw Municipal Cemetery. The Polish media tend to circulate false headlines which imply that when a Vietnamese person passes away, their ID documents are reused by someone else. I spent a few days taking images of Vietnamese graves in Warsaw in order to challenge this myth.

Mai Tran: “I came to Poland seven years ago and I work in finance, although I am currently on maternity leave. My partner is Italian, and we’ve recently had a baby, Sofia. She is learning Vietnamese, Polish, Italian and English. I cook her different foods and she already loves durian!

“Most of my friends are international, and I like to spend time with the expat community in Warsaw. I find it difficult to connect with Polish people. My contact with the Vietnamese community is also limited, and I am really interested in finding out how other Vietnamese people live. Everyone expects you to speak Polish fluently, but the language is really hard.

“I came to Poland because I was working too much in Vietnam, and I have a better life-work balance here. Poland was the first foreign country I visited, and it was a big culture shock. It was cold and everything was different. I’ve had some nasty stuff said to me like ‘Go to London and ask Polish people to come back to Poland’ or ‘Vietnamese people occupy Poland’. It wasn’t easy to hear, especially as my life is here, and I don’t want to go back to Vietnam.”

Duc and her daughter: “I came to Poland around two years ago with my two children and my mother. Unfortunately, my mother passed away, so it’s been quite difficult. I now have a Polish boyfriend and I am five months pregnant. With him I speak English, but my children go to a Polish school and picked up the language very easily, so they speak Polish with him.”

Filip Tran: “I don’t feel either Polish or Vietnamese are my languages. I am 12 years old. I came to Poland a few years ago, and I prefer to speak English.

“I can’t read Polish easily or have a full conversation in Polish. I don’t feel myself in Vietnamese, but I speak it at home. I feel out of place at big family gatherings, where everyone is speaking at the same time. Being Vietnamese doesn’t automatically mean that you understand each other, and there are things about Polish culture that I don’t understand either.”

“I am a Polish priest, but I spent four years living in Vietnam. I organise Polish lessons for the Vietnamese community in Warsaw with a Vietnamese nun. We hire a classroom in Wólka Kosowska. The lessons are free and run off donations. We also hold two Catholic masses a week in Vietnamese, and about 50-60 people tend to come.

“Many of those people find it difficult to adapt to Polish culture, but for some Vietnamese people Christianity is the motivation to come to Poland. It’s difficult to be a Christian in Vietnam, as that’s something that the Vietnamese government would ideally like to suppress.”

Jacky/Minh: “I’ve been in Poland for a year, but before that I used to live in Australia. I came to Poland on my own to learn about European culture. Most of my family is in Vietnam and the US, and my friends are in Singapore.”

“I was shocked by the similarities between Poland and Vietnam, mainly by the fact that Poland has its own cultural rules that you need to obey, if you want to function in society. What makes a Vietnamese person? First, you need to know the cultural rules and traditions. Second, you have to respect older generations. I feel half Vietnamese and half international, and I speak better English than I do Vietnamese.”