Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Aleks Szczerbiak

The uncertain geopolitical situation means that international issues could play a significant role in Poland’s crucial presidential election, although the extent depends on a news cycle out of the candidates’ control.

It could help the liberal-centrist ruling party’s candidate by overshadowing the government’s unpopularity and producing a pro-incumbent “rally effect”, although his support for a stronger EU defence identity is risky given most Poles still see the USA as Poland’s only credible military security guarantor.

A crucial election

This spring, Poland will hold a crucial presidential election, with the first round of voting scheduled for 18 May and a second round run-off a fortnight later between the top two candidates if none secures more than 50%.

Poland’s electoral commission has confirmed the final list of candidates who will compete in next month's presidential election.

The total of 13 contenders is the joint-highest number to have ever stood for the presidency https://t.co/awO6lnTbTZ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 14, 2025

In December 2023, a coalition government led by Donald Tusk, leader of the liberal-centrist Civic Platform (PO) which once again became the country’s main governing party, took office following eight years of rule by the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party.

However, the Tusk government has had to “cohabit” with PiS-aligned President Andrzej Duda, and lacks the three-fifths parliamentary majority required to overturn his legislative veto. This means that the presidential election will have huge implications for whether the ruling coalition can govern effectively during the remainder of its term of office, which is set to run until autumn 2027.

The two presidential frontrunners are: PO deputy leader and Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski, who lost narrowly to Duda in 2020; and PiS-backed head of the state Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) Karol Nawrocki.

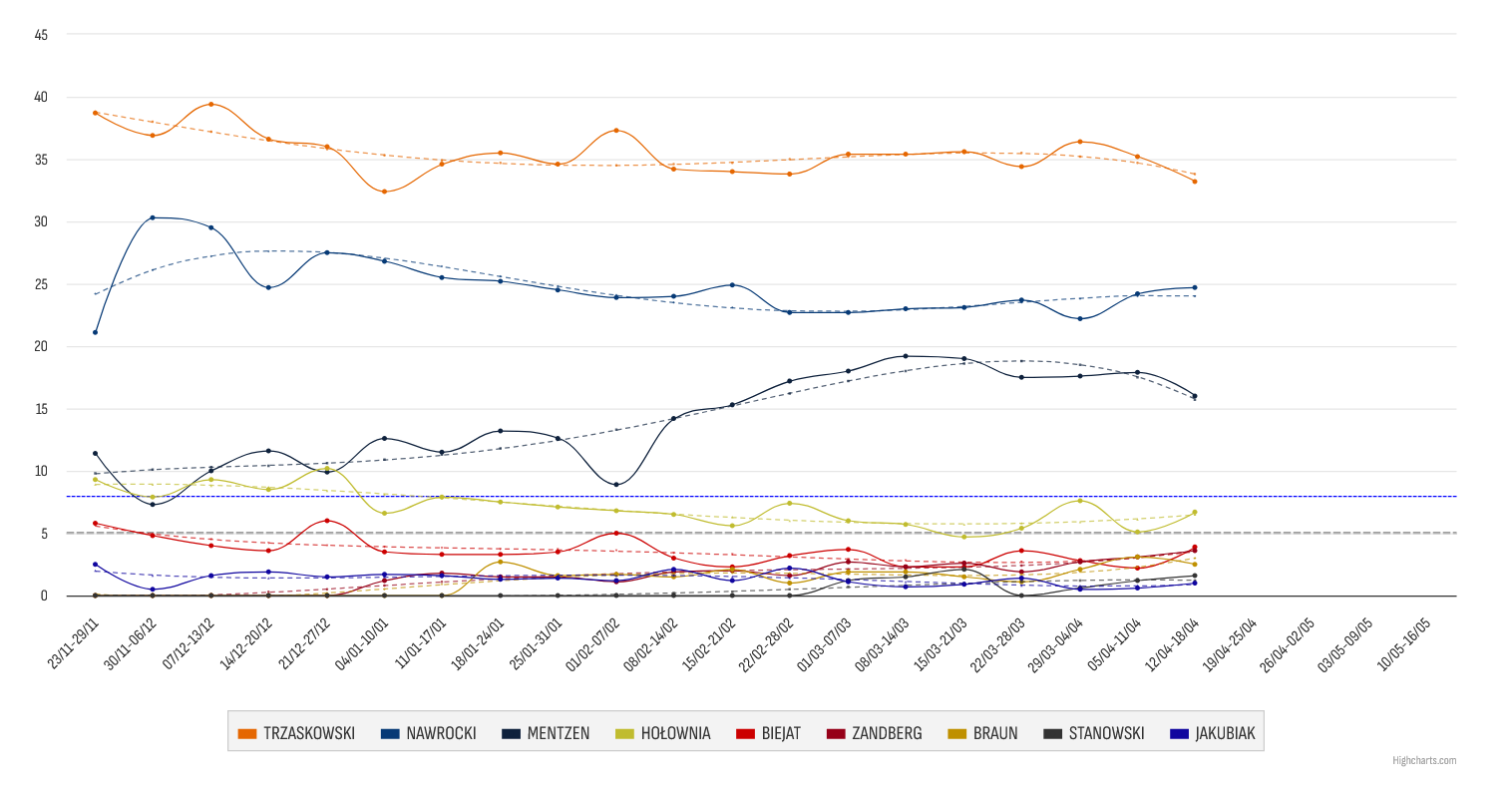

According to the Politico Europe‘s opinion poll aggregator, Trzaskowski is currently averaging 33% support compared with 22% for Nawrocki; while every poll published to date (except for one outlier) shows the PO candidate winning a second round run-off.

Weekly average of polling for the main candidates in Poland’s presidential election, compiled by ewybory.eu

Guaranteeing relations with Washington

It was widely assumed that the election campaign would be dominated by domestic political and socioeconomic issues. However, the changing and increasingly uncertain geopolitical situation means that these have, at times, been overshadowed by the different candidates’ approaches to international security.

Originally, PiS hoped that its close relationship with re-elected US President Donald Trump would work strongly to Nawrocki’s advantage. During Trump’s first term, which overlapped with PiS’s rule in Warsaw, the two saw themselves as strong ideological allies and forged a very close working relationship.

PiS politicians backed Trump in his re-election bid and enthusiastically celebrated his return to the White House in the hope that ties with the new administration would be strengthened even further.

Poland's conservative opposition enthusiastically welcomed Trump's return to the White House, but it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to maintain a tough anti-Russian line while also showing allegiance to the US president, writes @danieltilles1 https://t.co/4PW6H9nMEF

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 7, 2025

On the other hand, not only do the current governing parties lack ideological kinship with Trump, in the past PO leaders have been extremely critical of the US president. For example, Tusk once accused Trump of having ties with the Russian security services, while foreign minister Radosław Sikorski described the president as a “proto-fascist”.

Given that the USA is Poland’s most important military security ally, PiS hoped that, in addition to boosting the party’s morale more generally, Trump’s victory would allow it to argue that Nawrocki was a much better guarantor of good relations with Washington rather than a presidential candidate such as Trzaskowski, who is closely aligned with the current government.

Uncertainty about Trump

However, PiS and Nawrocki’s arguments became less appealing when Trump started to give the impression that he could help bring about a regional peace settlement on terms that could be perceived as unfavourable to Ukraine and emboldening Russia. Trump also appeared to question the continued US commitment to maintaining European military security as part of its NATO obligations.

Many Poles were particularly disorientated by Trump’s very public Oval Office clash with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and (temporary, as it turned out) halting of US military aid to, and intelligence sharing with, Ukraine.

Polish Nobel Peace Prize winner Lech Wałęsa and 38 other former political prisoners of Poland's communist regime have condemned Donald Trump's treatment of Volodymyr Zelensky on Friday, which they said reminded them of communist interrogation techniques https://t.co/HUgCqVzlLz

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 3, 2025

For sure, many PiS voters and senior party figures have themselves become increasingly critical of Ukraine.

Nawrocki has, for example, raised doubts about Ukraine joining the EU or NATO until it takes Poland’s concerns about the two countries’ different approaches to historical issues, particularly the role of Ukrainian nationalists in the 1943 Wołyń massacre of Poles, more seriously.

PiS also called for patience, arguing that results were more important than rhetoric and that Trump’s aggressive declarations could simply be a negotiating tactic and the price of bringing Russia to the negotiating table.

However, Poland’s geographical location means that it feels particularly vulnerable to Russia’s imperial ambitions. There is growing anxiety in Poland, as in other eastern European frontline countries, that Russia could swiftly regroup after peace negotiations brokered by Trump and pose an even greater security threat.

This is a final appeal for our emergency campaign to save Notes from Poland.

Next week, we may lose the major grant that sustains our work.

If you value the service we provide, please click below and make a donation to help it continue https://t.co/0gVkMlaA0W

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 22, 2025

Poles are also concerned about any suggestion that Trump might scale down the US military commitment to NATO’s eastern flank.

For example, a March survey conducted by the IBRiS polling agency for the Rzeczpospolita daily found that only 33% of Poles viewed the USA as a dependable ally under Trump’s leadership while 46% expressed a lack of trust; although respondents were very divided on party lines. This may have been one of the factors stalling Nawrocki’s earlier steady increase in opinion poll support in January.

Strengthening EU defence capability

For their part, as well as trying to present a more conciliatory tone towards, and develop a working relationship with, the new US administration, Trzaskowski and the Tusk government have also argued that Trump’s election confirms that Europe needs to take more responsibility for its own security.

They have tried to portray themselves as being at the forefront of developing an EU defence capability not dependent on the USA. As part of this, Trzaskowski has attempted to boost his campaign by stressing his foreign policy credentials (he was minister for EU affairs in a previous PO-led government), speaking at the Munich security conference where all the main European and US leaders were gathered, and meeting with the French and Finnish presidents.

Europe must start “believing we are a global power” and strive for “defence independence”, said @donaldtusk ahead of today's London summit.

He pledged Poland's support for Ukraine but called for maintaining "the closest possible alliance" with the US https://t.co/3K37kr2GgR

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 2, 2025

Nawrocki and PiS, on the other hand, lacked the state instruments and contacts within the EU political and international foreign policy establishments to respond effectively to Trzaskowski’s diplomatic offensive.

PO was also attempting to go on the offensive by reviving a trope that it developed successfully in last year’s European Parliament (EP) election, when it argued that in practice PiS operated in accordance with Moscow’s interests because it undermined EU integration and unity, and therefore Polish national security.

This could be seen clearly during a row over a March European Parliament resolution supporting recent EU moves to become more involved in coordinating and supporting defence policy, which PiS MEPs voted against.

This led PO to accuse the right-wing party of undermining efforts to bolster European defence and unity in the face of Russian aggression. They argued that the resolution was particularly important because it included an amendment tabled by PO MEPs declaring support for Poland’s plans to strengthen security on its Belarusian and Russian borders, known as the “East Shield”, as one of the EU’s defence objectives.

Amid heated debate in parliament, Poland’s ruling coalition and conservative opposition have split in a vote on whether the country should support the EU's recent moves to become more closely involved in coordinating and supporting defence policy https://t.co/55wKgu1yoZ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 21, 2025

Washington still the only credible security partner

PiS responded by pointing out that, while they voted in favour of the “East Shield” amendment, the EP resolution’s overall effect was to transfer powers over defence away from all EU member states to Brussels and the major European powers, leaving Poland with less control over its own security.

PiS said that it was absurd to suggest that the party and its presidential candidate were pro-Moscow, pointing out that Nawrocki had long been vociferously anti-Russian and proudly boasts that he is on a list of those wanted for arrest by the Russian authorities.

Although it supports increased defence spending by all NATO members, PiS and Nawrocki said that the idea that the EU can ensure the continent’s security without the USA was a pipe dream that would take years to come to fruition.

They also argued that, by pivoting towards a separate EU defence identity, PO and Trzaskowski would drive a wedge between Poland and the USA, and accused them of fermenting an “anti-American rebellion” and thereby undermining NATO.

Poland’s President @AndrzejDuda met with @realDonaldTrump today on the sidelines of @CPAC.

The @WhiteHouse said afterwards that the meeting had “reaffirmed our close alliance” and that Trump praised Poland’s high level of defence spending https://t.co/8P2uztujJm

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 22, 2025

However critical many Poles may be of Trump, most of them still view the USA as Poland’s only credible security guarantor. For example, a March IBRiS survey for the Polityka weekly found that more than 60% of the respondents felt there was no alternative to the transatlantic alliance, while 85% recognised the US’s strength as a military power compared with less than half who said this about the major European states.

Aware of this, PO and Trzaskowski have been very cautious about publicly criticising Trump since his re-election, and careful to present themselves as both favouring greater European unity and input into defence expenditure while emphasising the fundamental need to maintain the closest possible ties with the USA and NATO regardless of the changing international situation.

Overshadowing government unpopularity?

Trzaskowski has also benefited from the fact that the uncertain international situation distracted voters’ attention away from the Tusk government’s unpopularity and problematic record on domestic issues.

If the presidential election were to become a referendum on the Tusk administration’s domestic record, which Nawrocki and PiS have been attempting to turn it into, and voters use it to channel this growing discontent, then this could be extremely problematic for the PO candidate.

May's presidential election "will be a referendum on rejecting Tusk’s government", said opposition candidate @NawrockiKn in a speech today

He pledged to lower taxes, end Ukraine's "indecent" treatment of Poland, and reject the EU's "sick" climate policies https://t.co/pBCnlmH60Q

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 2, 2025

However, the unstable international outlook may also have produced, at least partly, something of what political scientists call a “rally effect”: the inevitable psychological tendency for worried citizens to unite around their political leaders and institutions as the embodiment of national unity when they feel that they face a dramatic external threat.

For example, according to the monthly tracking poll conducted by the CBOS agency, the government saw its approval rating increase from 31% in January (43% disapproval) to 36% in February (39% disapproval, and only 38% in March), its most positive ratings since June 2024.

Geopolitical uncertainty has also meant that voters seemed somewhat less concerned about the possible concentration of power and lack of checks and balances within the political system if the president and government were to come from the same political party. Rather, it may have made them more inclined to prioritise cooperation between the two branches of the executive as a way of strengthening Poland internationally.

Out of the candidates’ control

Whether and to what extent international politics influences the presidential election, therefore, depends upon whether foreign affairs overshadow domestic issues, particularly evaluations of the Tusk government’s overall performance. This, in turn, depends on the very unpredictable ebb and flow of the global news cycle and so, ultimately, is out of the candidates’ control.

Although the international context in the election run-up is likely to be dominated by the Ukrainian peace negotiations, their outcome and whether Trump’s “reset” with Russia will be considered a triumph or blunder will probably not be known until after the May-June presidential poll.

If there is a peace settlement on terms that are clearly unfavourable to Ukraine, and Trump’s actions make the USA appear a destabilising international actor, this could be very problematic for Nawrocki. On the other hand, although it might increase the attractiveness of a potential EU security vector, Trzaskowski’s position is not necessarily a winning one if this is felt to undermine the transatlantic alliance.

Moreover, given the risks of an ongoing war in Ukraine spilling over into Poland, many Poles would probably be prepared to accept a peace settlement as long as it guaranteed the functioning of Ukraine as an independent state and ensured that a pacified frontline was as far away as possible from the Polish border.

For the first time, a majority of Poles believe the war in Ukraine should end even if it means Kyiv ceding part of its territory or independence.

Support for that view now stands at 55%, more than double the 24% found two years ago.

Read our full report: https://t.co/3XDTjQlSZA pic.twitter.com/qLHZxoBkQi

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 20, 2024

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Rafał Trzaskowski/Facebook