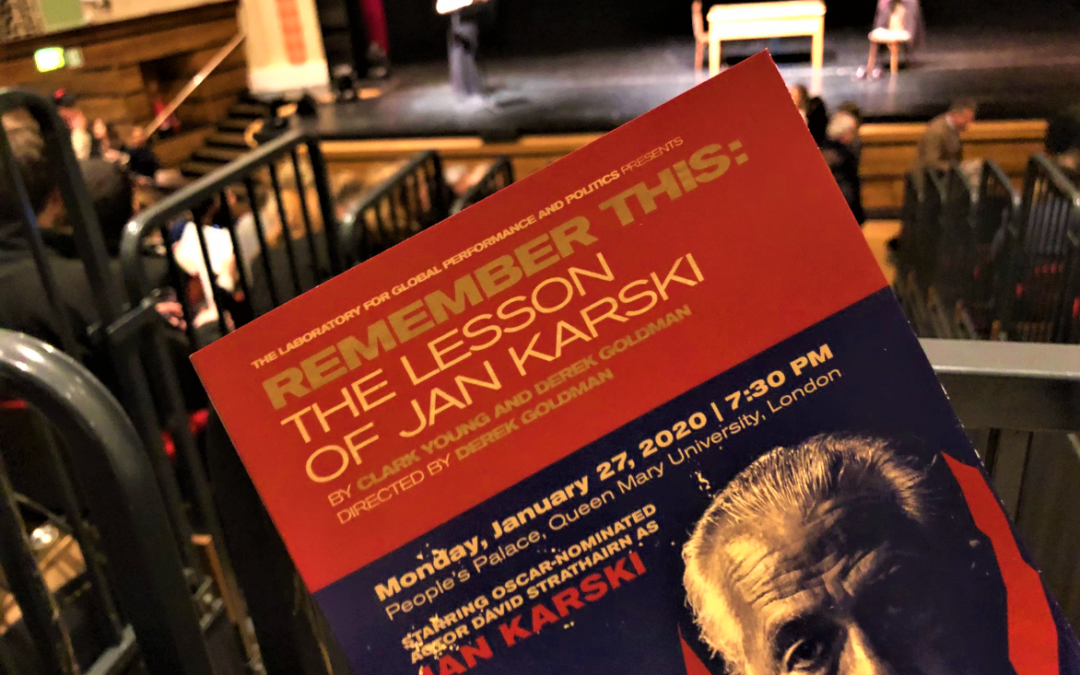

By Stanisław Skarżyński

There was a moment during the performance of Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski when one member of the audience could not keep his emotions in check.

“Idiot!” he snapped in the darkness of the People’s Theatre at London’s Queen Mary University.

The outburst came when Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, told Jan Karski, the Polish underground courier who had witnessed firsthand the Warsaw Ghetto and a transit camp for Jews on their way to the Bełżec , that he would not allow him to meet Winston Churchill to tell him about the situation in German-occupied Poland.

It may well have been a revelation to some of the audience watching David Strathairn’s performance in this one-man play, which marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, that, despite Karski’s meeting with Eden, Churchill informed parliament in 1946 that during the war he had had no knowledge of the scale of the death industry created by the Nazis to eliminate European Jews.

***

The production might seem crude, but that is not a bad thing. It is still a work in progress, and from a performative standpoint it is founded on the mastery of Strathairn (previously an Oscar nominee for his role as Edward R. Murrow in Good Night, and Good Luck), who acts as if his aim were to not let his audience forget that this is only theatre. Theodor Adorno’s famous line – “writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric” – seems to be present throughout.

Jan Karski is often described as a hero. But here, the simplicity and detachment reduce his wartime story from a heroic one to that of an everyman, bounced around like a rag doll during a historical tempest. The play addresses the question of the role of the witness, the one who lives on to give testimony which people are more likely to ignore than listen to; the one who is incapable of altering the course of events but is also not a victim. “I’m a machine,” Karski tells himself in Strathairn’s voice.

But the witness perspective only goes so far. Remember This… is a well-researched work that shows how the Holocaust had deep roots in the fabric of the West well before the war, and that when it happened no one had any idea how to react. There is a clear line in the play, linking Polish antisemites of the interwar era, Western leaders’ reluctance to act in response to the Holocaust, and the displeasure of Polish audiences and authorities both in London and Warsaw when Karski appeared in Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 documentary Shoah.

This impotence is all-consuming. A rare moment of genuine honesty comes with the sentence from Jewish US Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, who rejected Karski’s report. “I did not say that he was lying, I said I could not believe him. There is a difference,” he explained later.

Amazing role of @DStrathairn playing Jan Karski, who infiltrated the ghetto in German occupied Poland and informed the world about the Holocaust. Followed by a panel discussion moderated by @raziaiqbal which provoked many questions from the audience pic.twitter.com/BDmxGfsfgH

— British Poles (@britishpoles) January 27, 2020

***

This performance is not aimed at recreating the past or judging the various characters played by Strathairn, as the only conclusion here is acknowledging how privileged are we, that we cannot even try to imagine being a part of that time.

One cannot put oneself in the shoes of Roosevelt and Churchill, who bore the world on their shoulders, who despite endless failures and dirty compromises led their unwilling societies into the war, and finally won it.

Or of the representative of the community of Polish Jews in London, Szmul Zygielbojm, who killed himself in 1943 to protest against Western societies’ “looking on passively upon this murder of defenceless millions of tortured children, women and men.”

Or of the boys who threw rats at Jews in Łódź for fun, yet probably did not understand the link when they soon became witnesses to the annihilation of the victims of their pranks.

During the public discussion that followed the performance, Strathairn mentioned Karski’s decades of silence after the war. In his opinion, this was the result of a severe post-traumatic stress resulting from his experiences.

But for this explanation to be sufficient it needs to be expanded to the entire society, because no one asked Karski for his testimony. For a long time after the war, any enquiry into the Holocaust was pushed away from the public sphere, reduced into a historians’ subject. And it wasn’t only a cover-up for the guilty consciences of those who failed their Jewish neighbours – the silence was needed also on the survivors’ side, as so many refused to give their testimony and never spoke about the war or the Holocaust.

One need not look far: for over two decades of their marriage, Karski and his wife, Holocaust survivor Pola Nirenska, never spoke of the war or the Shoah. She never read his book, and he had to buy himself a ticket to her dance performance – In Memory of Those I Loved…Who Are No More – because she did not want him to see it. In 1992, days before her 82nd birthday, she leapt from the balcony of their 11th-floor apartment.

In an interview with Hannah Rosen in 1995, Karski said: “It was easy for the Nazis to kill Jews, because they did it. The Allies considered it impossible and too costly to rescue the Jews, because they didn’t do it. The Jews were abandoned by all governments, church hierarchies and societies, but thousands of Jews survived because thousands of individuals in Poland, France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland helped to save Jews. Now, every government and church says, ‘We tried to help the Jews’, because they are ashamed, they want to keep their reputations. They didn’t help, because six million Jews perished, but those in the government, in the churches they survived. No one did enough.”

***

Leaving the theatre into the safety of the streets of London, one could only appreciate not to have been living at a time when evil reached its peak. But this is a convenient lie, as in fact millions have perished since and continue to do so: in Cambodia, Rwanda, the Balkans, Sudan and most recently in Myanmar and Syria.

The key to this play about Jan Karski is the word “lesson” in its title. The lesson is that there is a point of no return, that once things spiral out of control there is no redemption and that evil, including the ability to commit atrocities, is a persistent part of the human condition that crawls beneath the surface, inconspicuously reaching out as a temptation to divide “us” from “them”, then stigmatise and dehumanise “them”, then…

Perhaps a present-day example is needed, as paragraphs like the one above are being printed one after another and yet the memory of the Holocaust fades with every passing day.

A few days ago, a Polish far-right magazine launched an attack on Tomasz Grodzki, the opposition speaker of the upper house of the Polish parliament, seeking to establish whether he has Jewish heritage. The author concluded that “the face of the new speaker and his lively gesticulation may indicate that he is of Jewish or semi-Jewish origin”.

The explanation offered by the author for undertaking his rather lazy investigation, reads: “It would not make sense if he were content with the position of doctor, baker, waiter or athlete, but given that he has political ambitions to such an extent that he is the speaker of the Senate, his origins are very important. Origins are of huge importance in politics!”

It is hard to imagine the Polish state in its current form taking any serious action in response. Just to mention few examples: Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki’s remarks about “Jewish perpetrators” of the Holocaust. President Andrzej Duda, during the presidential debate of 2015, criticising former president Bronislaw Komorowski over his apology for the Jedwabne massacre. The far-right demonstrators’ chanting at Duda “take off the kippah, sign the bill” outside the presidential palace. The same bunch marching in Warsaw with a huge banner reading “Poland for the Poles”. All of these went by without any meaningful reaction.

Or the man who yelled about “standing up to Jewish invaders” at the gates of Auschwitz during last year’s commemoration of the liberation of the camp. He was sentenced to one year of community service. “Jews will be soon running the f*** away from this country”, he commented on the court’s ruling.

To realise in 2020, that this individual considers himself to be a representative of the same nation that Karski represented in London and Washington, is to realise how badly we need new attempts at reviving that lesson, and Remember This… is a wise and powerful attempt to meet that challenge.

Main image credit: QMUL/Twitter

“Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski” was produced by Georgetown University, where Karski served as a longtime professor after the war, to mark the centenary of its School of Foreign Service.