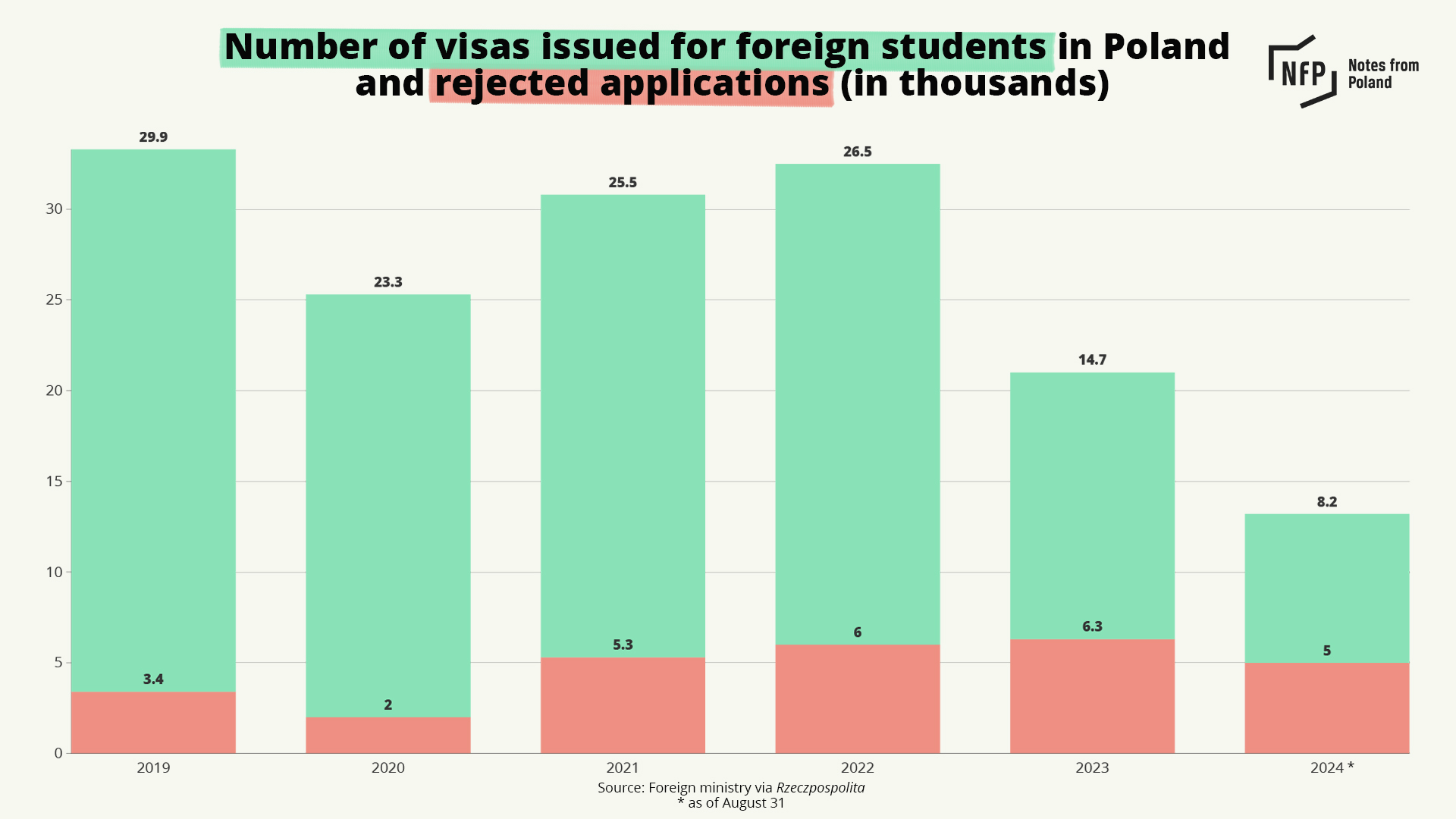

The number of visas issued to foreign students in Poland has declined significantly this year while the proportion of applications being rejected has increased. The largest number of refusals were issued to applicants from Iraq, Nigeria and Turkey.

The development follows a clampdown by the new government after evidence of abuses in the system under the previous administration. It is believed that student visas were often used as a backdoor to come to work in Poland or to gain access to the European Schengen Area.

But there are now concerns that the new restrictions will cause problems for Polish universities that rely on the tuition fees of foreign students as a source of income.

By the end of August this year – around one month before the start of the new academic year – Poland had issued around 8,200 student visas, according to data from the foreign ministry obtained by the Rzeczpospolita daily. That was down from 14,700 in the whole of 2023 and 26,500 in 2022.

Meanwhile, this year almost 38% of decisions issued on student visa applications have been negative, compared to 30% in 2023 and 18% in 2022. In 2020, the figure was as low as 8%.

The countries that recorded the highest numbers of refusals were Iraq (704), Nigeria (497), Turkey (479), Ethiopia (270), Bangladesh (247) and Pakistan (246). In the case of Bangladesh, around 70% of applications were rejected. The majority of successful applications, as in previous years, come from Ukraine and Belarus.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. The article continues below.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

The declining visa numbers and rising rejection rates have come after reports began to emerge last year of widespread irregularities in Poland’s visa system, including claims that corruption had allowed some individuals to pay to expedite their application.

A report by the state audit office that was leaked to a newspaper this week found that the former Law and Justice (PiS) government, which ruled Poland from 2015 until the end of 2023, had overseen an “unlawful, corruption-prone” visa system.

Among the auditors’ findings was that, due to IT failings, it is impossible to verify whether 17,000 student visas were issued correctly because the necessary information was not entered into the system and relevant documents were only stored by the foreign ministry for a year.

A report by Poland’s state auditor has found large-scale irregularities in the issuing of visas under the former PiS government.

Over 366,000 were granted to people from Asia and Africa while others were given to Russians after the invasion of Ukraine https://t.co/13bcJkfA2C

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 24, 2024

In May this year, a white paper prepared by the foreign and interior ministries under the new government that replaced PiS in office likewise pointed to irregularities in the student visa system.

“Foreigners have abused the overly easy recruitment [process] to study in Poland, and their real purpose of entry was to work or emigrate to other Schengen countries,” reads the document

Rzeczpospolita notes that around half of foreign students in Poland did not make it to the second year of their studies.

🔴TYLKO U NAS. Zagraniczni #studenci mają coraz więcej problemów ze zdobyciem wizy

Kliknij w zdjęcie, by przeczytać więcej🔽https://t.co/M1Rms3dcKN

— Rzeczpospolita (@rzeczpospolita) September 26, 2024

Subsequently, at the end of July, foreign minister Radosław Sikorski introduced stricter guidelines for consulates when assessing student visa applications. They can now require the applicant to have a decision issued by a Polish education board recognising their foreign diplomas.

The development has led to concern that Polish universities will suffer amid a decline in lucrative tuition fees from foreign students.

A spokesman for the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, one of Poland’s two best colleges, told Rzeczpospolita that its recruitment of foreign students was down only very slightly compared to last year. But it remains to be seen “how many of them will actually show up for classes on 1 October”, he added.

Kraków’s student population has shrunk by almost 40% in just over a decade.

To stem the decline, the city – famous for its universities, in particular the 660-year-old Jagiellonian – is hoping to attract more students from abroad https://t.co/1Vlq2vgNTl

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 4, 2024

However, it is private universities – rather than public ones like the Jagiellonian – that are seen as most at risk. At the Academy of Applied Sciences in Lublin, 72% of all students are from abroad. At the Vistula University of Finance and Business in Warsaw, 57% are.

Krzysztof Szymański, who works for an agency, Marhaba Poland, that helps recruit foreign students to Polish universities, told Rzeczpospolita that the new rules “were introduced at the wrong time, during the recruitment process at universities, without consulting them”.

“This has a terrible impact on the reputation of our country,” he added, predicting that, as a result of the changes, the number of foreign students coming to Poland – which has boomed in recent years – could fall by 40-50%.

The number of foreign students in Poland has exceeded 100,000 for the first time.

The figure, now 105,400, has tripled in the last decade and almost 9% of all students in Poland are now from abroad https://t.co/XPYL0ExCh7

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 20, 2023

Main image credit: NAWA/MNISW (under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 PL)

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.