By Stuart Dowell

In the well-populated pantheon of Poland’s Second World War heroes, few figures shine as bright as Elżbieta Zawacka. She operated as an undercover courier in occupied Europe, was the sole woman in an elite Polish paratrooper group, and was only the second woman in the Polish army to achieve the rank of brigadier general.

A new biography, Agent Zo – whose title refers to Zawacka’s nom de guerre – explores her life and achievements. According to its author, Clare Mulley, one of the aims of her book is to change perceptions that have become calcified over decades.

“In the UK when people think of the resistance in occupied Europe they think of the French. I hope this book will highlight the huge role of the Polish underground during the war, and also the work of women in the underground.”

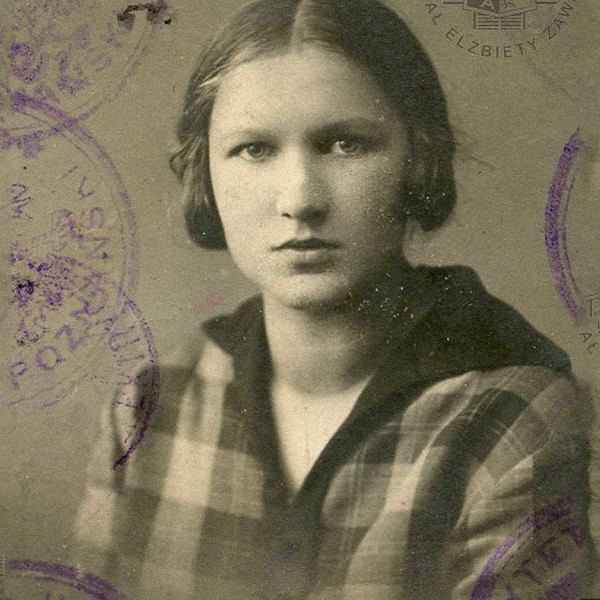

Elżbieta Zawacka. Photo credit: Institute of National Remembrance

Mulley’s book reveals that Zawacka lived a double life even as a young child. The seventh of eight children, she was born on 19 March 1909 in Toruń.

At the time, Toruń was in the Prussian Partition of Poland, where signs and symbols of Polishness were outlawed. Her father, a court clerk, would have lost his job if he had been overheard speaking Polish.

As a result of this campaign of cultural erasure, Zawacka was forced to suppress her Polish identity. At school, she was taught German and was thus unable to speak Polish until she was 11.

She recalled a situation from 1920 – after Poland had regained independence – when General Józef Haller entered Toruń at the head of the Polish Army.

“My dad held my hand. We were marching with his friends. When he heard the national anthem, tears flowed. It was the first time I saw men crying. They were moved by hearing Polish speech.”

“Without an independent Ukraine, there cannot be an independent Poland,” said Józef Piłsudski in 1919. “We cannot believe anything Russia promises.”

A new biography of Poland’s founding father shows how relevant he remains, writes @derJamesJackson https://t.co/r7bXGDqLi8

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 26, 2022

After finishing school, Zawacka studied mathematics at the University of Poznań. While there, she attended an information meeting of the Women’s Military Training (PWK). This decision initiated her into a lifetime of service to her country.

The organisation was formed during the battles for Poland’s borders after the First World War. In newly independent Poland, it ran horseback riding camps, taught map reading and organised lectures and excursions.

Zawacka was swept away by its spirit of camaraderie and service. She joined the organisation and became an PWK instructor in 1931. By 1937, she was appointed commander of the Silesia district.

“She was regarded as sharp and demanding of others, but most of all of herself,” wrote fellow wartime courier Jan Nowak Jeziorański. “Her devotion to duty bordered on fanaticism…She was stern, serious, a little rough and very matter-of-fact.”

Elżbieta Zawacka (centre) as a platoon commander in 1939. Photo credit: Pomeranian Archives and Museum of the Home Army

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Zawacka was 30 years old. She received urgent orders to travel to Lwów, where she joined a women’s battalion to defend the city from a German assault.

Upon hearing that the Germans were displacing Poles from Pomerania, she returned to Toruń to make sure her family was safe.

She was soon sworn in to the resistance and returned to Silesia, where she took on the mission of creating an underground network.

The area was now part of the Third Reich and thus populated with German speakers. Yet in less than two months she recruited 300 people to the underground

“Her perfect German, Aryan appearance and self-confidence made her ideal for clandestine work,” says Mulley.

Poland today marks the 80th anniversary of the formation of the Home Army, a resistance movement that emerged during the Nazi-German occupation and which is believed to have been the largest such underground force in Europe https://t.co/9sKsfVskrg

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 14, 2022

She worked as a courier travelling between the General Government that the German occupiers had established after invading Poland and the Third Reich, carrying weekly reports on troop movements, the work of administration offices, and on mines.

Discovery by the Gestapo was an ever-present threat. In the event of a slip-up, the Germans would try to break Zawacka under brutal interrogation. She carried poison with her to prevent this.

On one mission travelling by train from Kraków to Warsaw, she realised that she was being followed. When the train slowed down, she slipped out of her compartment to the toilet and jumped out the window onto gravel.

“I was covered in blood, but I crawled to the nearby forest,” she recalled.

She made it to Warsaw, but her cover was blown. The Gestapo arrested her sister Klara and her parents, as well as around 100 underground operatives.

Today marks the 77th anniversary of the beginning of the Warsaw Uprising.

Memory of the struggle has been strongly influenced by the work of Sylwester Braun, a member of Poland’s underground resistance who photographed the dramatic and tragic eventshttps://t.co/OprNr0Y0vX

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 1, 2021

Her sister survived the war as a prisoner in German concentration camps, while her parents were released after several days of detention. Her brother Egon was also a victim of German repression and died in Auschwitz.

“We women soldiers of the Home Army were not afraid of death. We were afraid of arrests and torture, and that we would not endure it. If I hadn’t been lucky a hundred times, I would have been dead a hundred times.”

By this time, Zawacka had caught the attention of the Home Army command, which asked her to join the Foreign Liaison Department responsible for communication between the Home Army and the Polish government-in-exile in Paris (later, in London).

Posing as Elizabeth Kubitza, an employee of a German oil company, she attempted to reach Britain in December 1942 to deliver a secret report held on microfilm in a cigarette case, but only managed to reach Paris.

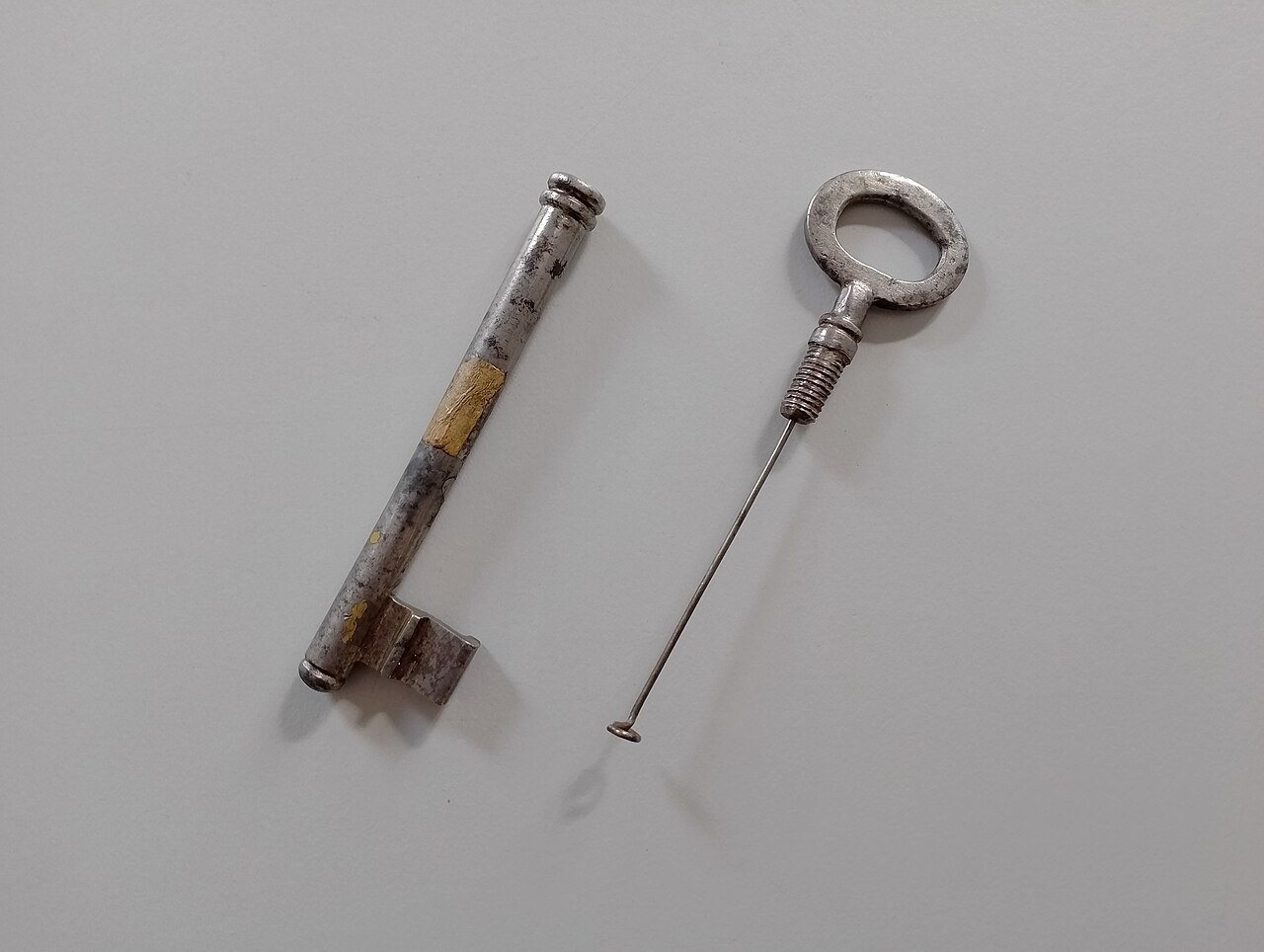

She made another attempt in February 1943, this time with the microfilm hidden in the shaft of a key. Despite many dangers, she reached London via France, Andorra, Spain and Gibraltar.

Key used by Elżbieta Zawacka to carry the microfilmed reports from the Home Army Headquarters. Photo credit: General Elżbieta Zawacka Foundation in Toruń

In London, she met with the prime minister of the government-in-exile, General Władysław Sikorski. However, he showed little interest in the information she had brought from Warsaw.

Zawacka was frustrated that the Poles in London did not understand the realities of occupied Poland and the conditions under which she and other couriers worked.

“Delays in communication when couriers were en route forced them to stay in one place for longer, exposing them to great risk,” Mulley explains. “These were traditional pre-war Polish men in uniform and when they met Zawacka in a skirt and blouse they didn’t know how to treat her.”

A room at the European Parliament has been named after Witold Pilecki, the Polish underground officer who deliberately had himself imprisoned at Auschwitz during WWII to gather intelligence and organise resistance at the camp https://t.co/bQHkJRDbp3

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 16, 2023

While in London, she had another important mission to persuade the government-in-exile to recognise women serving in the Polish army as fully-fledged soldiers with rights to pay and rank.

After much discussion, on 27 October 1943, President Władysław Raczkiewicz signed the Decree on Women’s Voluntary Service.

Having achieved this, she reported her readiness to return to Poland and was sent on a course for the Silent Unseen, an elite group of commandos who were trained to parachute into occupied Poland and carry out special operations.

She was the only one among a dozen female volunteers to complete this challenging course, which lasted several months. On the night of 9 September, she jumped into Poland from a Halifax bomber along with 16 other commandos.

“I will never forget the date. I was the only woman,” she later recalled.

While in 🇬🇧, Zawacka joined “The Silent Unseen”—the elite Polish Special Ops paratroopers trained in the UK to carry out covert ops, sabotage and intelligence-gathering in occupied Poland. She was the only woman in the unit. She parachuted into #Poland in Sept. 1943.

5/9 pic.twitter.com/bZbUxqI61d

— Marta Karpińska (@MarKarpinska) March 19, 2023

Underground operatives waiting at the makeshift landing site near Warsaw were dumbfounded when they encountered not only a woman but one wearing a dress.

During the Warsaw Uprising, she served as a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Service and helped with nursing work. After the fall of the Uprising, she went into hiding and later tried to reestablish underground communication routes.

After the war, she continued her studies and returned to teaching maths in Łódź, Toruń and Olsztyn.

However, in a wave of repression against former members of the Home Army, she was arrested by the communist authorities in September 1951. She received a sentence of five years in prison, which was later extended to seven, then ten. She was released in 1955 after four years under the Amnesty Law.

After regaining her freedom, she continued her work and academic career with characteristic vigour, earning a doctorate in 1965.

The son of Witold Pilecki – a Polish officer who deliberately had himself imprisoned at Auschwitz to organise resistance there – is seeking 26 million zloty (€5.5m) compensation for his father’s postwar death at the hands of the communist authorities https://t.co/ftCKeanLrt

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 9, 2022

Over the years, she kept in touch with her underground colleagues. She created archives to preserve the memory of members of the Home Army. All this in the face of the threat of repression by the communists, who never allowed her academic career to fully develop.

In the 1980s, she was active in Solidarity, the movement that led opposition to Poland’s communist government. It was only after the fall of communism that the country she had served with so much fortitude was able to appreciate her commitment.

In the 1990s she was promoted to the rank of colonel, and in 2006 to brigadier general, making her only the second woman in the history of the Polish army to achieve the rank.

Elżbieta Zawcka. Photo credit: Institute of National Remembrance

Until the end of her life, she remained extremely active, contributing to veterans’ organisations and working for the Home Army Foundation, which she co-founded. While in her nineties, she learned how to use the internet to maintain an archive of her former Home Army brothers and sisters in arms.

She died two months before her 100th birthday, on 10 January 2009. Her body was buried in her home city of Toruń at a funeral that was attended by thousands.

Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Fearless WW2 Resistance Fighter Elżbieta Zawacka is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson and was released in the UK on 16 May.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Pomeranian Archives and Museum of the Home Army