By Alicja Ptak

Since Russia’s invasion, thousands of IT workers have been relocated from Ukraine to Poland, allowing their businesses to continue functioning – and indeed thriving – while also contributing to the war effort.

The first three days after the war broke out were a blur for Olga Kuraksa, a 42-year-old senior executive at Ciklum, one of the biggest IT companies in Ukraine.

She had arrived in the northern Polish city of Gdańsk just a few days earlier. And even though she had agreed when her company suggested a temporary relocation, she never believed Russia would actually invade her home country. In fact, she had a return ticket booked for mid-March.

“I think that I spent the first 72 hours at work,” says Kuraksa, country manager at Ciklum (pictured above at the firm’s Gdańsk office). Together with a colleague, she established a hotline for employees who wanted to relocate and the phone started ringing non-stop.

Whiteboard in Ciklum’s Gdańsk office

Ciklum, just like many other Ukrainian IT companies, offered relocation schemes both within the country and abroad, mostly to Poland. Some 2,000 of its 3,200 employees accepted the offer in the early days of the war, including 250 who moved to Poland.

“We put [them] on buses; we funded the petrol if they drove their own vehicle; we paid for train tickets and plane tickets. However, they needed to go to a safe place,” says Patricia Taylor, Ciklum’s chief human resources officer. The company also covered the costs of hotel rooms and a per diem to help with any additional costs of relocation.

“It was the right thing to do from a humanitarian perspective” but also “a smart thing to do from a business perspective”, adds Taylor.

And such efforts by Ciklum and several dozen other Ukrainian IT companies paid off. According to the IT Ukraine Association, industry capacity was maintained at 96%. Three of the biggest Ukrainian IT companies told Notes from Poland that their teams remained nearly as effective as before the war, partly thanks to the relocation efforts.

This means that the booming IT sector, a backbone of the Ukraine’s economy, could maintain growth, albeit slower, even after Russia’s invasion in late February. In the first quarter of 2022, including over a month of the war, the sector’s export income reached a record $2 billion.

Before the war, the sector employed 285,000 IT professionals and contributed 23.5 billion hryvnia (€750 million) to the state budget in 2021 alone.

How do you work when the bombs are falling?

Another major Ukrainian IT company, Infopulse, moved 400 of its employees and 600 of their family members to Poland. But not everybody managed to leave.

Initially, Infopulse planned to move 500-700 employees, up to 35% of its staff and d when the war broke out on 24 February, Infopulse employees with families headed for the border. But barely a dozen male workers crossed over before Ukraine banned all Ukrainian men between the ages of 18 and 60 from leaving the country.

However, seeking to protect its employees, the company still managed to relocate 1,600 workers and their families to western Ukraine, which has been least affected by the war and is considered relatively safe.

To be able to work seamlessly, Infopulse and other companies implemented measures to allow their teams to remain safe and productive even in case of falling bombs, as well as power and internet outages. They booked apartments for relocated employees, refurbished bomb shelters, installed additional power generators and secured Starlink, a satellite internet service operated by Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Bomb shelter in Infopulse’s Lviv office

“If you want to help us, work with us”

Ivan Korzhov, the head of Infopulse in Western Ukraine, says that for the first three weeks of the war he worked nearly non-stop, helping with internal relocations. A sense of mission sustained his efforts, however. He was doing this not only to help his colleagues. He also feels his work contributes to the victory of his country through the money it provides.

“There is a common phrase in Ukraine right now, that we in Ukraine don’t want peace, we want victory,” said Korzhov. “We want to work, we want to win. And we understand that all that we are doing, our taxes, our initiatives, and our volunteering is all for one cause basically, for us to get our land back. For us to free our people in occupied territory.”

Infopulse employees in the bomb shelter. Ivan Korzhov, Lviv regional manager, sits in the centre

According to IT Ukraine Association, the sector contributes to the state’s coffers on average 222 million hryvnia (€7.15 million) in taxes every month.

Some employees who have relocated abroad also try to pay taxes in Ukraine for as long as it is legally possible – which in Poland’s case is up to six months. Others donate a big chunk of their salaries to causes that are important to them.

While they are grateful for the international help provided by other governments, organisations, individuals and even their own clients, the message they give is: “If you want to help us, work with us”.

Screenshot from a report by Ukraine IT Association

“From the point of view of Ukrainian industry, it is not a problem that these people left,” says Łukasz Olechnowicz, the head of Infopulse in Poland. “The bigger problem…is that some customers do not want to sign contracts if the services are delivered from Ukraine or if the company is located in Ukraine.”

As the war broke out, some customers became anxious about business continuity; others asked the companies they were working with to relocate some of their operations out of the war zone due to security reasons.

“For some of our clients, security issues are very important and they cannot afford to give access to their systems when there is a risk that Russian soldiers would take over a laptop on which an employee is working,” says Olechnowicz.

While big companies such as Ciklum and Infopulse maintained nearly all of their customers, as they were able to transfer some of the operations abroad, smaller businesses, collectively paying the most in taxes, lost some of their clientele. In the case of the smallest companies, those hiring up to 200 people, contract retention was 88%, compared to 99% for the biggest firms.

What does this mean for Poland?

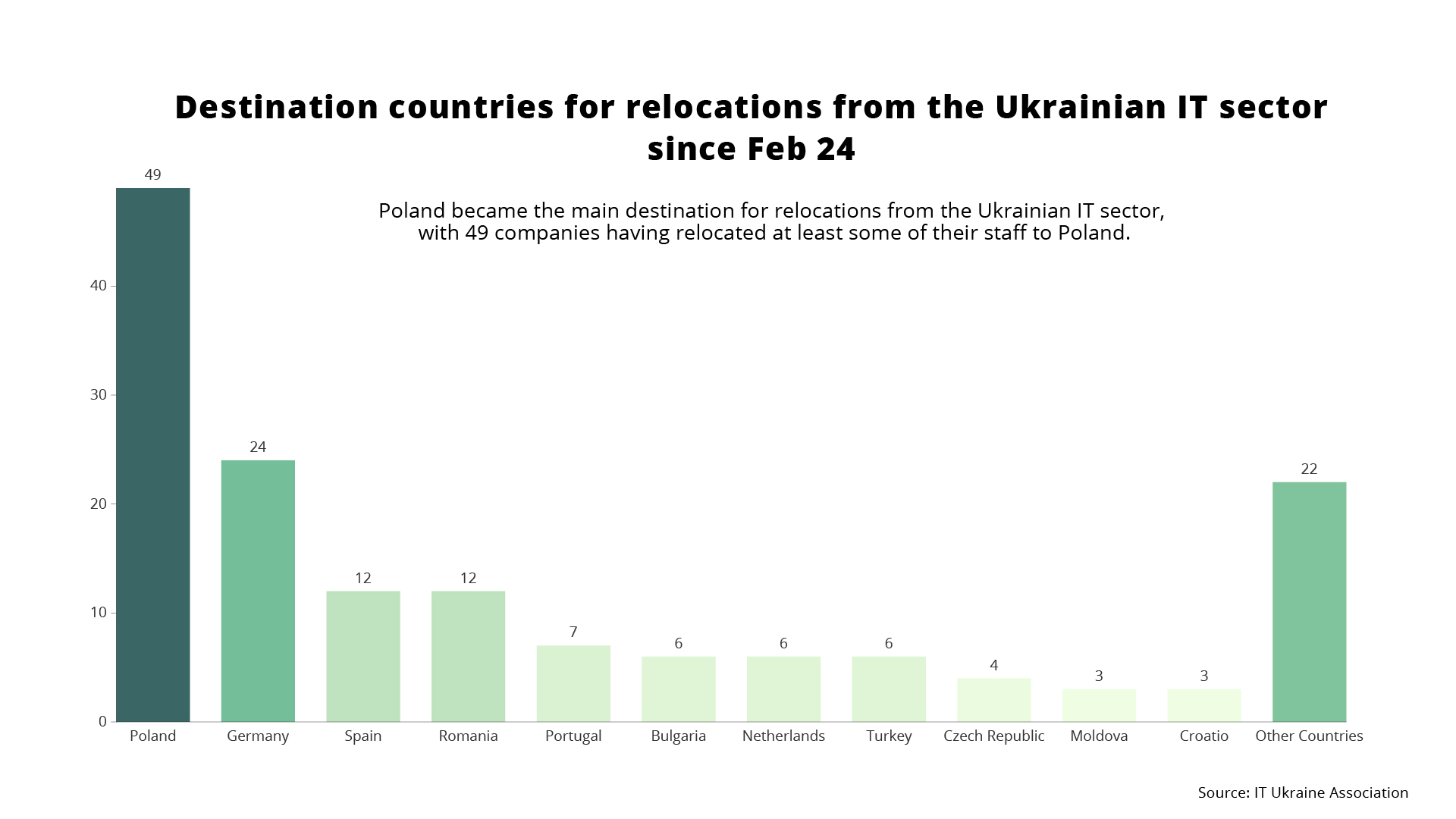

In total, 49 companies have relocated at least some of their staff to Poland and 21 companies plan to open an office there, making Poland the main destination for relocations from the Ukrainian IT sector.

Before the war, N-iX, another major player in the IT sector in Ukraine, had only five specialists in Poland. But by 1 June there were 120 of them. And they are keen on hiring, both in Ukraine and in Poland.

“We planned to develop our Polish office long before the war, but it has definitely accelerated this initiative,” says Oleksandr Shatnyy, the head of HR at N-iX. “You want to go to the place that resembles home as much as possible, and Poland is the closest to that. We don’t feel like emigrants in Poland… we feel like neighbours and friends.”

After nearly four months in Poland, Ciklum’s Olga Kuraksa can share that sentiment. She says she feels supported and welcome in Gdańsk, a city where Ukrainian flags are visible on many corners.

Polish and Ukrainian flags at Gdańsk Shipyard, near Ciklum’s Gdańsk office

On her left wrist, she wears a bracelet made from blue-yellow and white-red strings, symbolising Ukrainian-Polish friendship. Having taken care of her colleagues, she can now start settling into her new life in Gdańsk.

She says that while she thinks that there are a lot of opportunities to grow in Ukraine, as a mother of two, she would only feel safe to return if Russia capitulated and Ukraine was part of the EU.

Olga Kuraksa typing on a keyboard. The bracelet made from blue-yellow and white-red strings symbolises Ukrainian-Polish friendship

“Mutually beneficial”

Both the Ukrainian and the Polish IT sectors voice a willingness to work together. According to Wiesław Paluszyński, the president of the Polish Information Processing Society (PTI), the reconstruction of Ukraine after the war will be a great opportunity for Polish companies. “Ukraine is a huge market,” he says.

Konstantin Vasyuk, executive director at IT Ukraine Association, proposes strengthening collaboration right away. He thinks that Ukraine and Poland should work together on creating a Central European IT hub, which could serve companies from all over the world.

“We know that we are now closer than ever before and we can develop this closeness to be mutually beneficial for both nations, for both countries,” he said. “We shouldn’t wait until the war is over. We can do it right now.”

Main photo credit: Alicja Ptak

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.