By Daniel Tilles

Poland has become a vegan hot spot, with Warsaw named the third most vegan-friendly city in the world. But, in a deeply conservative country, this challenge to traditional cuisine has provoked a backlash, with veganism seen as part of a broader threat to Polish culture, values and even religion.

Tucked away in a nondescript street on the outskirts of Kraków’s city centre is a milk bar that, in most respects, looks like any other of these traditional Polish canteen-style eateries.

It is small, slightly shabby, and has a clientele drawn from a cross-section of society – students, families, pensioners, local office workers – attracted by quick service, hearty portions and low prices.

Yet the name of the establishment reveals that it is far from typical: the Polish for “milk bar”, bar mleczny, has been replaced by Bezmleczny, meaning “Milkless”, symbolising the fact that its menu is completely free from dairy (as well as meat, eggs, and any other animal products).

Among the dishes on offer, many of which mimic those of a traditional milk bar, the most popular, says owner Wojciech Pankowski, is a vegan version of kotlet schabowy. This Polish staple is normally a slab of pork, breaded and fried. But in this case, the meat is replaced with a soy substitute.

Pankowski initially served the dish only on Fridays, which is when Catholic Poles traditionally eschew meat. But it proved such a hit that it is now sold all week round.

Bezmleczny’s kotlet schabowy

Bezmleczny’s adaptation – some might say subversion – of an iconic Polish institution, the milk bar, and of classic dishes such as kotlet schabowy is emblematic of the way in which veganism is challenging norms in Poland.

It is also one of the reasons why veganism has become yet another battleground in Poland’s bitter culture wars between liberals – who are willing, even keen, to question cultural and social traditions – and conservatives, who are determined to protect them.

This conflict is particularly intense among the young, who are contesting Poland’s identity on several fronts, including LGBT rights, religion, the environment, gender roles, and now even dietary habits.

The third most vegan-friendly city in the world

For anyone who visited Poland up to the early 2000s, when a vegan would struggle to find much beyond the tasty but rather basic surówka side salads, it can come as a surprise to learn that the country has become a major destination on Europe’s vegan map.

In 2017, Warsaw was picked as the third most vegan-friendly city in the world by Happy Cow, the leading vegan restaurant guide. Recent data from a Polish food-delivery firm indicate that Kraków, Wrocław, and Poznań have even more vegan establishments in proportion to their population than the capital.

Surveys suggest that Poland’s vegan community now numbers in the hundreds of thousands. Add in vegetarians, and the figure rises to a million or so – over 3% of the adult population.

This, however, only tells part of the story. The most recent of those studies found that almost half the population (43%) are not giving up meat completely but “severely limiting their consumption”. It is these consumers who are above all driving demand for plant-based products, according to Patrycja Homa, director of ProVeg Polska.

This is a view borne out by the experience of Cezary Bartkowski, owner of Vegano, a cafe in Kraków serving sandwiches, salads, and smoothies. Around 70-80% of its customers are meat-eaters, he says.

Many are attracted by the fact that Vegano was ranked as the number one restaurant in Kraków on TripAdvisor. (At the time of writing, it has slipped to second spot – overtaken, ironically, by a steakhouse.)

Some initially laugh when they learn that the “ham” in their sandwich is made from coconut oil, while the “egg” is actually flavoured tofu. “But the best thing for me is when people on a traditional diet come to our place, try it, and say ‘that was delicious’,” says Bartkowski, who admits that running the business is for him as much about popularising veganism as about making money.

A number of specialist food firms have also emerged to meet this demand, many making their products as meat-like as possible. One company, Bezmięsny (Meatless), describes itself as a “vegan butcher”, offering a range of sausages, bacon and the like. Since being founded with just two employees three years ago, it has grown rapidly, and now supplies products to supermarket chain Auchan.

Products from “vegan butcher” Bezmięsny

“We want to give people an opportunity to limit meat in their diet without a sense of self-sacrifice,” says Klara Siemanowska, the head of marketing at Meatless. People often cut down on or give up meat for ethical and environmental reasons, but “they still like the meat flavours they grew up with,” she adds.

Big Polish food firms have also cottoned on to this trend and are trying to join the fast-growing market for vegan products. Even leading meat and dairy producers, such as Sokołów and Łowicz, now offer a range of plant-based hams, cheeses and other replacement products. Petrol stations serve vegan hot dogs alongside traditional ones.

Beware Marxist vegetarian cyclists

These developments have not been without controversy. Indeed, veganism has become something of a symbol in Poland’s bitter culture wars, which pit conservatives and liberals against one another on a wide range of social issues.

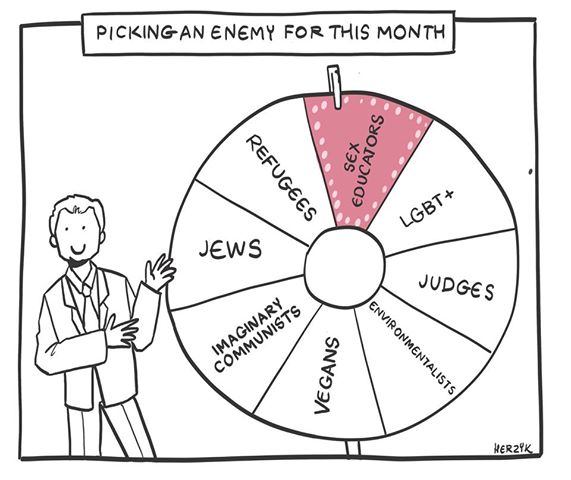

Soon after the current conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government came to power, its foreign minister warned of the need to combat the “leftist programme of the previous government,” which followed a “Marxist pattern” of creating “a new mix of cultures and races, a world of cyclists and vegetarians, who use only renewable sources of energy and fight against all forms of religion”.

This “has little in common with traditional Polish values,” he warned.

His words illustrated that, for some on the Polish right, vegetarianism has become bound up in a range of modern, progressive ideas that together threaten the traditional way of life, including Poland’s dominant Catholic faith.

“In some circles, what doesn’t fit the narrow, often national-Catholic approach to the world is referred to as undefined ‘leftism’,” says Siemanowska. “Vegetarianism is perceived as a threat” by those who consider themselves “real Poles, real patriots”.

A new documentary film project, titled “Carnivore: Enemy Number One”, promises to expose the fact that, while veganism “may seem innocent”, it is in fact an “unethical and immoral ideology” seeking to bring about an “anti-Christian and anti-human revolution” by “taking apart social, cultural, economic and religious structures”.

The group behind the film is part of a network of ultraconservative Catholic organisations that has led campaigns in Poland against a wide range of perceived threats. The issues it promotes are often soon adopted by mainstream conservatives.

One of its branches, the NGO Ordo Iuris, was responsible for a proposed law banning abortion, which reached parliament in 2016 but was abandoned by PiS after it prompted mass protests by Polish women.

Ordo Iuris was also behind a campaign against “gender ideology” that was picked up by PiS while in opposition. This year, the same themes have been revived as PiS, now in government, raises concern over the “LBGT ideology” that it claims threatens Polish tradition, faith, and culture.

It appears that veganism is now the next target.

A recent cover of right-wing news magazine Do Rzeczy asked (and answered): “Who wants to ban us from eating meat? The new madness of the left”. Inside, a columnist warned that the “eco-left”, after coming after Poles’ right to eat meat, will then attack “many of our other freedoms”.

Image by Aleksandra Herzyk / Instagram: @aleksandraherzyk

Neo-Nazi attack

The most serious incident came earlier this year in Gdańsk, where three vegan restaurants were vandalised with neo-Nazi imagery and slogans. Police quickly arrested three individuals on suspicion of carrying out the attacks, revealing that their apartment had been filled with “fascist symbols and images”.

The content of some of the slogans that appeared on the restaurants – such as “We will f**k up you leftist whores” and “Homo is deviancy” – again demonstrate how veganism is seen by some as part of a broader progressive threat.

Dziś naszą ekipę w drodze do pracy powitał taki widok. „Nigdy dość rasizmu i faszyzmu w Trójmieście”. DOŚĆ! I nigdy…

Opublikowany przez Avocado vegan bistro Sobota, 16 marca 2019

“It was a very hard time for us,” says Daniel Jaroć, owner of Faloviec, one of the restaurants that was targeted. “Identifying veganism with ‘leftism’ is stupid, because anyone can become vegan regardless of [their] ideology.”

“In 50 years’ time we will be ashamed that we ate meat”

Yet it is clear that Poland’s vegan community – at least the most active and visible elements of it – is often supportive of liberal social issues.

Visit the toilets at Lokal Vegan Bistro, a trendy Warsaw eatery, and you find yourself surrounded by stickers supporting causes such as LGBT rights. Posters advertise AKS Zły, a local football club that recently won UEFA’s best grassroots club award for its work promoting gender equality, combating homophobia and racism, and seeking to integrate refugees and players with disabilities.

Leading figures in Poland’s liberal cultural elite are vegans, such as author and recent Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk, who says that “in 50 years’ time we will be ashamed that we ate meat”.

Another recent cover of Do Rzeczy warned that Tokarczuk – who is seen as insufficiently patriotic by many Polish conservatives – is trying to “serve us an indigestible diet” in which “non-Poles are more important than Poles, non-Catholics than Catholics, and animals than people”.

Robert Biedroń, a former LGBT activist who is now the leader of the progressive Spring (Wiosna) party, is a vegetarian. At Spring’s launch event earlier this year, the catering was reportedly exclusively vegan.

One of Spring’s newly elected MEPs, Sylwia Spurek, complained about the lack of vegan food in the European Parliament canteen, posting a picture of the meagre options on offer. In a later tweet, she suggested “creating new laws to ensure that the production of animal products is more difficult and expensive”.

Both posts elicited amusement and anger in equal measure from conservative commentators.

A to jedzenie wegańskie, jedyne, na jakie mogę liczyć w stołówce Parlamentu Europejskego ? Była dzisiaj jeszcze opcja…

Opublikowany przez Sylwię Spurek Środa, 17 lipca 2019

Poland’s divided youth

Another feature of the division between vegans and their critics is the role that age and gender plays.

Vegans in Poland are disproportionately female, as indicated in surveys as well as from the experience of those involved in the industry.

Most clients of Bezmiesny, the “vegan butcher”, are women. “Perhaps the multigenerational experience of women as an excluded and discriminated group makes it easier for them to feel empathy [with animals],” suggests Siemanowska.

Vegans also tend to be young. This can create tensions within families, which in Poland tend to be more close-knit than in many Western European countries and for whom shared meals, especially during religious holidays, revolve around meat, fish, eggs, and dairy.

Paulina, a 24-year-old student, decided to go vegetarian at the age of 11, but initially hid it from her family, secretly feeding meat from her plate to the dog. At 19 she went vegan.

After having “the talk” with her family, the reaction was difficult. “My mum cried sometimes,” says Paulina. “My grandma was very persistent, always offering me meat even though she knew I’d refuse.”

Yet in the public sphere, the most vocal opponents of veganism are almost invariably men. And, like the vegans themselves, they tend to be on the younger side.

This situation is certainly not unique to Poland, but there is also a specifically Polish aspect to it. Young Poles are increasingly divided along gender lines, with women on average much more liberal and young men holding more conservative, often nationalist, views.

Only 36% of men under 30 support introducing the right to same-sex marriage, for example, compared to 59% of their female peers.

Asked in a recent poll what the greatest threat facing Poland is, the most common answer among young men was “gender ideology and the LGBT movement”, while for women it was the climate crisis. (Concerns at the environmental costs of animal farming are a motivation for many vegans.)

Young men also express stronger attachment to traditional gender roles and family structures.

These differences are also clear in voting patterns, with young women most likely to support Spring or other parties with a leftist or liberal hue, while young men favour the nationalists of Confederation or the ruling national-conservative PiS.

A survey of young Poles (18-30) by @Kantar shows how drastically different young men and women are from one another.

Men are much more nationalist and traditionalist while women are more liberal and progressive. More detail on the data in thread below 1/5 https://t.co/79ezTTCckU

— Notes from Poland ?? (@notesfrompoland) May 2, 2019

It is therefore not surprising that, as young women embrace a secular, liberal, progressive identity, one that questions many traditional norms, some turn to veganism. For precisely the same reason, it is regarded by many young men as yet another challenge to the traditional Polish values and practices that they see as increasingly under threat.

What it means to be Polish

This suggests that veganism will continue to serve as a front in Poland’s growing culture wars. Skirmishes tend to cycle through different theatres: immigration and multiculturalism; abortion and reproductive rights; climate and the environment; gender and sexuality.

Very often it is youths on the front lines: such as the predominantly male nationalists protesting against LGBT parades or Muslim refugees, or the women who led the “black protests” against proposed abortion bans and the recent youth climate strikes.

Poland’s young generation, the first to have the luxury of growing up entirely in the post-1989 period of freedom and democracy, are contesting what it means to be Polish. And diet is increasingly at the heart of this conversation.

Additional reporting by Iga Szczodrowska

Main image credit: Vegano

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.