By Daniel Tilles

Critics accuse Poland’s government of seeking to introduce measures that would limit free speech. But it is often overlooked that they already have a powerful set of tools at their disposal to stifle debate, restrict artistic freedom and intimidate opponents.

This month, a 67-year-old man was charged with the crime of insulting a monument for placing a t-shirt reading “constitution” on a statue of former president Lech Kaczyński (pictured above). Last month, prosecutors launched an investigation into whether two men at an LGBT pride parade who added a rainbow flag to the national coat of arms (pictured below) had publicly insulted a state emblem, an offence that carries a prison sentence of up to one year. Earlier this year, a poet, Jaś Kapela, was found guilty of contempt for the nation after changing some words of the national anthem (adding a reference to refugees). Although he successfully challenged the verdict, the appeals court instead found him guilty of contempt for the anthem of the Republic.

The flag displayed at an LGBT march that prompted an investigation. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

These are just a few recent cases, and only a sample of some of the things it is illegal to insult in Poland. Other crimes include offending religious feeling (punishable with up to two years in prison); insulting the Polish nation or state (a different offence from showing contempt for the nation, and one that carries up to three years’ imprisonment); and humiliating constitutional organs of the state (up to two years in prison) or insulting a public official (up to one year in prison).

Another crime, insulting the president (which can land the perpetrator behind bars for up to three years), has been pursued to bizarre and petty extremes. In 2006, police spent months tracking down a homeless man who had drunkenly said that the then president, Lech Kaczyński, was a “thief”. Two years later, a man was put on trial for creating a computer program that made President Kaczyński appear at the top of search-engine results when someone typed in a slang word for penis. Under Kaczyński’s successor, Bronisław Komorowski, an unemployed teacher was traced and charged for anonymously writing a vulgar comment about the president under an article online.

Other countries in the EU also have “insult laws”. But few criminalise such a wide range of perceived insults and punish them so severely. An OSCE study published last year found that, among nine types of defamation and insult laws, Poland has the joint most and, unlike many other countries, imposes custodial sentences for all of them. The wording of its laws is also often broader and vaguer, making it easier to apply them. In Germany, for example, it is illegal to “publicly defame” religious beliefs in a manner “that is capable of disturbing the peace” – a far narrower, more specific offence than Poland’s crime of “offending religious feelings”.

The large number, broad applicability, and relative severity of Poland’s insult laws provide the authorities with a powerful set of tools to stifle free speech and harass opponents. Even when left unused, their mere existence has a chilling effect, discouraging people from expressing themselves freely on certain topics. (Enforcing the laws is also a waste of state resources that could be better spent on dealing with more serious crimes.)

Rights groups such as Amnesty International have condemned Turkey’s Article 301, which punishes the “denigration of the Turkish nation” and its various state organs with up to two years in prison. In 2011, the European Court of Human Rights declared that Article 301’s “scope…is too wide and vague and thus constitutes a continuing threat to…freedom of expression”. Yet, as we have seen, Poland’s insult laws punish the same offences in a similarly vague manner, and with even longer prison sentences. Of course, in practice the law has not been used in the manner and to the extent that it has in Turkey, but the potential is there.

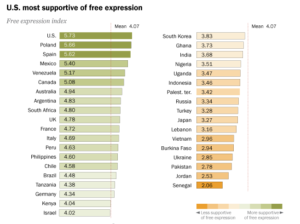

This state of affairs is particularly ironic given that many Poles pride themselves on being free of the political correctness they believe has caused so much harm in the West. A recent Pew poll found that Poles were the European people most supportive of free expression. Yet, given that political correctness essentially means avoiding language that could offend certain protected groups, Poland’s insult laws amount to a form of state-enforced political correctness – albeit one designed to protect the feelings of the dominant majority rather than marginalised minorities.

Pew poll on support for freedom of expression

This contradictory attitude is epitomised by the current ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party. Its leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, warns that “political correctness has eliminated freedom of speech in many countries of Western Europe” and promises that Poland will remain “an island of freedom even if everywhere else it is limited”. He adds that, “we of course will not accept any laws on hate speech”.

In actual fact, his latter comment is false. In addition to its insult laws, Poland, like other Western countries, also punishes hate speech against national, ethnic, racial or religious groups with up to two years in prison. Moreover, under the rule of Kaczyński’s party, insult laws have been eagerly enforced, thereby limiting people’s freedom of speech.

Kaczyński’s inconsistency, and the fact that he views the insult laws largely as a political tool, is also indicated by his changing attitude toward the crime of insulting the president. When his brother Lech was in office, Jarosław, then the prime minister, was happy for the law to be enforced; but when Komorowski, from the rival Civic Platform (PO) was in the presidential palace, Jarosław, now in opposition, called for it to be abolished. Since PiS returned to power in late 2015, with its candidate for president, Andrzej Duda, in office, any talk of repealing the law has disappeared.

However, although the current government is happy to make use of the insult laws, it cannot be blamed for their existence. All were passed under previous administrations. The most recent was added in 2014 by the previous PO-led parliament, which introduced special protection for the iconic Kotwica (Anchor) symbol that was used by the Polish underground resistance during WWII. The legislation, signed into law by President Komorowski, made it an offence to profane the Kotwica. (It also stipulated that “showing respect and reverence for the symbol is the duty of every citizen”.) The law was used last year to punish a woman involved in the “black protests” against a proposed abortion ban, who was found guilty for adding a pair of breasts to the anchor symbol on a placard (in the style pictured below, although the photograph does not show the woman who was charged).

However, while these laws have long been on the books, what makes the current situation particularly troubling is that the government has taken unprecedented control over prosecutors and, increasingly, the judiciary. This creates the potential for politically motivated cases to be more easily brought, and with a greater chance of successful prosecution. Even without direct interference from politicians, the growing number of prosecutors and judges ideologically aligned with, or at least seeking to gain the favour of, a ruling party that places patriotism and religion at the heart of its ideology will undoubtedly have an effect on the enforcement of laws intended to punish those who offend patriotic and religious sentiment.

Indeed, as we can see in the cases outlined above, it is often ideological opponents of PiS that are being targeted. The Lech Kaczyński statue stunt was carried out by anti-government protest group KOD (the Committee for the Defence of Democracy). The LGBT pride march was condemned as a “provocation” by the interior minister, while another more recent one was described as a “parade of sodomites” by the defence minister. The “black protests” have been one of the biggest manifestations of opposition to PiS.

The targeting of artists and performers is also a worrying infringement of creative freedom. In addition to the poet mentioned earlier, a well-known satirist is currently facing charges of insulting the Polish nation for writing that Poland is a “stupid, narrow-minded country”. Heavy-metal band Behemoth recently faced charges of insulting the state emblem because on a promotional poster they added devil’s horns and an inverted cross to the Polish eagle (pictured). That case was dismissed, but the band’s lead singer is now being investigated for offending religious feeling after waving a sex toy with an image of Jesus attached to it.

A play performed in Warsaw is also being investigated for offending religious sentiment after PiS MPs submitted a request to prosecutors. The expert opinion sought by the prosecutor’s office came from a Catholic theologian at Cardinal Wyszyński University (who also works as an advisor to the Catholic Church). He concluded that the play does offend religious feeling, making a conviction more likely. The organiser of Poland’s largest music festival, Jerzy Owsiak, whom the government perceives as an opponent, has twice in the last year been taken to court for swearing in public.

The fact that Owsiak has regularly sworn on stage at his festival previously without facing legal action points to a final problem with Poland’s insult laws: their inconsistency, both in scope and application. While in theory the religious sentiment of followers of all faiths are protected, in practice cases are brought almost exclusively when Catholics have been offended. Thus pop singer Doda was found guilty and fined for saying that the Bible was written by people “drunk on wine and smoking some herbs”, but far worse things are said about the Quran, or Islam more broadly, without any action.

Meanwhile, certain groups, most obviously sexual and gender minorities, are explicitly denied special protection from insult – meaning that the defence minister can attack “parades of sodomites” without losing his job, let alone facing any charges. In 2016, the small liberal party Modern submitted legislation to include the LGBT community and people with disabilities in Poland’s hate-speech law, but it was rejected by the PiS-dominated parliament.

It is understandable that countries have defamation laws, allowing individuals, groups and institutions to have recourse against false and harmful claims made about them. Likewise, legislation preventing the deliberate stirring of hatred towards certain groups is defensible. But insults, while they may be unpleasant, should be regarded as a normal part of discourse in democratic societies. People should not have a right not to be offended. This is even more the case when it comes to prominent public figures like the president, who should be prepared to accept criticism.

Poland’s turbulent and tragic history of occupation and foreign rule, during which national symbols and the church were often suppressed, make it understandable that the country now seeks to protect them. But having such a broad set of vaguely worded criminal offences carrying severe punishments creates a dangerous tool, particularly in the hands of an increasingly politicised judicial system.

Main image credit: @Kom_Obr_Dem/Twitter

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.