By Marta Jaroszewicz

This article is published in cooperation with the ideaForum of the Batory Foundation.

With its liberal system of issuing temporary work permits, Poland has become the European and global leader in terms of the influx of short-term labour from abroad. For the last two years running, it has issued more first residence permits to non-EU immigrants than any other member state, and it has the most temporary labour migrants of any OECD state.

However, as the country’s Supreme Audit Office (NIK) warns in a recent report, to maintain this position, Poland will need to improve the system responsible for issuing foreigners with residence and work permits, which is poorly organised and slow.

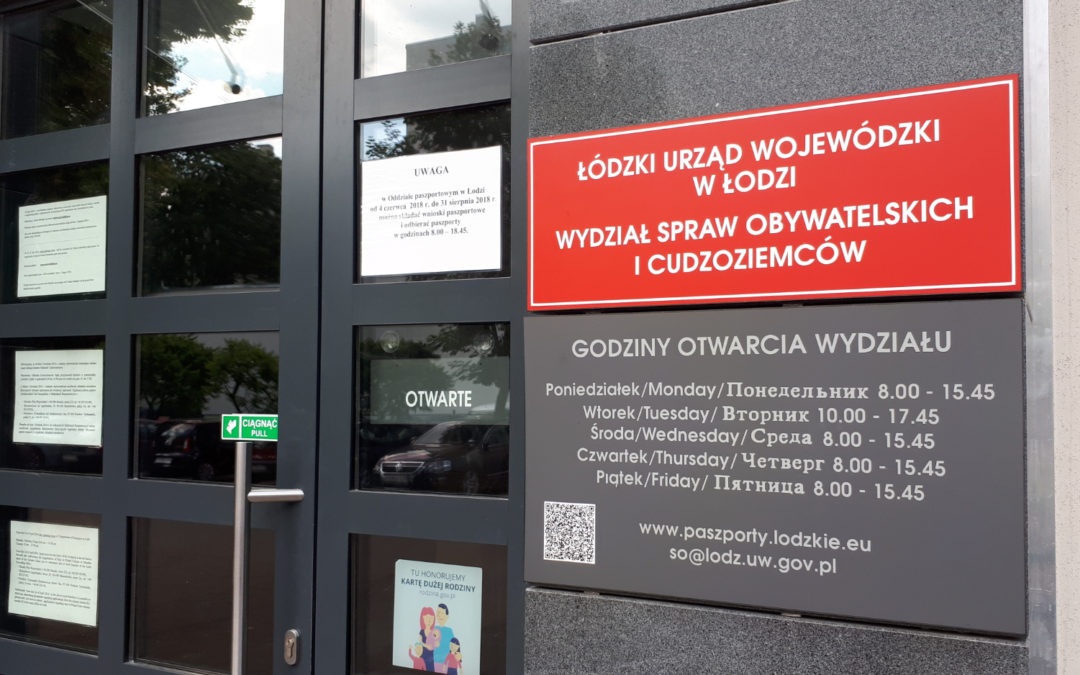

In August NIK published a report assessing the state administration’s readiness to serve foreign citizens, which checked how individual units were performing their duties. It also examined whether the existing system functioned effectively and whether supervision was carried out correctly. The inspection spanned a four-year period (2014–2018) and 19 institutions, including the Ministry of the Interior and Administration, the main body responsible for migration policy, and voivodeship offices, the provincial authorities that issue the permits.

Sluggishness and system failure

The report provides a wealth of empirical material. Earlier assessments of the system, formulated by experts who did not have full access to official figures, were inevitably incomplete. Based on data from across Poland, the new report concludes that the public administration is unprepared to smoothly process the rapidly growing number of foreigners coming to Poland.

When foreigners first arrive in Poland, attracted by the simplicity and speed of obtaining a statement from an employer about their intention to hire a foreign citizen, it is relatively easy to live and work in the country for six months. Yet if they want to stay for additional months or years, they encounter serious barriers. Obtaining a residence or work permit is a long and arduous process.

According to NIK, in 2014 it took 64 days on average to legalise a foreigner’s temporary stay in Poland. By 2018, this had risen to 206 days. Some 70% of cases at voivodeship offices and over 30% of those at the Office for Foreigners were handled in a way that violated provisions, the report adds.

Specifically, filing a request for a permit was made more difficult (physically caused by the long queues, with no way to register online), the first step in the case was delayed and official deadlines were missed. Most of the voivodeship offices and job centres inspected lacked directions and plans for processing foreigners’ paperwork. The rules were not formalised and officials failed to create an appropriate information policy.

Strategic supervision and management

There are multiple reasons for this situation. NIK highlights the insufficient and fluctuating staffing; there is not enough money to hire adequate numbers of people. Strategic thinking and management is also lacking. There are no clear guidelines (based on professional feasibility studies) applicable to all offices, enabling officials to manage resources in the most efficient and flexible way. The Ministry of the Interior and Administration is not overseeing the process properly, NIK points out. The supervision of voivodes was insufficient, it notes, as it failed to limit late decisions (as revealed by ministerial inspections, for example).

NIK revealed that, although officials have been working on a ministerial policy for supervising subordinate bodies since 2017, it is not yet complete. Moreover, the minister has not introduced a formalised policy for supervising the head of the Office for Foreigners. NIK also had reservations about how the execution of decisions on repatriation (made by border guards) was monitored.

Post-audit conclusions – what next?

The report seems to link the system’s inefficiency to Poland’s lack of a migration policy. The document from 2012 was annulled, and work on a new one, which began in 2016, has dragged on. However, it seems that merely adopting the document will not change much, especially if it is not based on a variety of analyses by experts and broad public consultations.

NIK rightly highlights the need to define and implement legal and supervisory solutions to streamline the legalisation of foreigners’ stay and work in Poland. For this, it seems necessary to implement a uniform system for processing foreigners’ paperwork to be used by all the administrative organs involved.

In addition to introducing a clear quality-control system, it could be based on high-tech solutions, such as a single database and a risk-analysis system. The new solutions could be based on the system used by Poland’s Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy to monitor statements on employers’ intention to hire a foreigner.

The original version of this article can be found here. Translated by Annabelle Chapman.