By Norman Davies

This article is published in association with The Relief Society For Poles Trust

The Cud nad Wisłą, or Miracle on the Vistula, was no miracle. It was a hard-fought battle, which took place in August 1920 near Warsaw and ended in a decisive Polish victory over the Red Army of Soviet Russia. It was won by the skill, discipline and determination of the Polish defenders; by the patriotic spirit of a large numbers of volunteers; and by Marshal Józef Piłsudski’s brilliant counterattack, which stopped the Soviet offensive in its tracks.

Only afterwards were theories put forward by Piłsudski’s nationalist opponents suggesting that victory should be ascribed either to General Maxime Weygand or to Providence. The height of the battle happened to coincide with the Feast of the Assumption, when many Polish Catholics prayed for their country’s salvation. So, people naturally felt their prayers had been answered.

Suppressed knowledge

As a student of Modern History at Oxford, I never heard a word about the Polish-Soviet War; it had no place on the intellectual radar screens of British historians. But I began to mend my ignorance on the subject as soon as I visited Poland in the early 1960s.

An early source of information was my future father-in-law, Professor Marian Zieliński, who lived in Kęty near Bielsko. He explained that Communist censorship was suppressing knowledge of the Soviet defeat, adding that everyone knew what had really happened thanks to the experiences of their families. He himself had fought in the war as a teenager and went on to describe some of his amazing adventures.

In the summer of 1920, the young Marian Zieliński was a 16-year old pupil in the gymnasium of Tarnów, a town well known for its recent patriotic support for Piłsudski’s Polish Legions. As the school year was finishing, he and most of the boys in his class skipped school, walked the 300 km to Warsaw, found a recruiting office, lied about their age, and joined the army.

There was no time for formal training. The “Bolshevik hordes” were already on the march. The young volunteers were assigned to the Siberian Brigade, which consisted of trained Polish conscripts from the disbanded Tsarist Army and which had escaped from Russia via the Far East; each of them was paired up with a hardened veteran, who was ordered to teach the teenager on the way to the front how to load, fire and clean their heavy English rifles. They were sent to the fortress of Modlin, where General Władysław Sikorski’s Fifth Army was deployed.

General Władysław Sikorski with soldiers of the Polish 5th Army during the Battle of Warsaw (Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe/public domain)

Then, following Sikorski’s successful action on the River Wkra, they pushed northwards towards the Prussian frontier, where, near Chorzele, they ran into the “Red Cossacks” of Ghai Khan. This was to be Marian’s baptism of fire. Kneeling behind a thorn bush, he struggled desperately with his jammed rifle, as a sabre-wielding Cossack charged.

Closing his eyes from fright, he heard the galloping hooves, the swish of the whirling sabre and the single shot fired by his veteran companion. The Cossack fell dead from the saddle; and the riderless horse rolled over them both, man and boy.

For me, who had never fired a gun in anger, the combination of these romantic tales with the frisson of “taboo” proved irresistible. In the eyes of a budding historian, there is nothing so attractive as the forbidden fruit of officially denied events. Polish history in the years 1918-21 became the first topic of my academic research, and eventually of my very first book.

In those days, I cannot remember anyone talking of the “Polish-Bolshevik War”. English books talked (inaccurately) of the “Russo-Polish War”, usually very cursorily and invariably with the assumption that it was Poland which had attacked Russia and not vice versa. Official Polish textbooks, if they mentioned it at all, wrote of the “Wojna Polska-Radziecka”, which, they said, was “pursued in the interests of the great Polish landowners”, which “brought enormous losses to the country”, and which ended mysteriously after the Red Army chose to retreat.

For myself, seeing that the new-born Polish Republic was confronted by the armed forces of three Soviet republics – Soviet Russia, Soviet Belarus and Soviet Ukraine – I have always called it the “Polish-Soviet War”, and kept to the formula in my book, White Eagle, Red Star, published in in 1972.

The Polish-Soviet War

The war between Poland and the Soviet republics lasted from February 1919 to the ceasefire of October 1920 and was formally ended by the Treaty of Riga signed on 18 March 1921. (Incidentally, it was concluded prior to the formation of the Soviet Union in 1923. Another frequent mistake is to say that Poland was fighting the Soviet Union.) It is important to stress, however, that the fighting occurred in two distinct phases, and that each phase had its specific characteristics.

The 1919 campaign was essentially territorial. In the first year of its existence, the Polish Republic, like most of the neighbouring states, was struggling to establish its frontiers. Further East, the Russian Civil War between “Reds” and “Whites” was in full flow, and in many non-Russian provinces of the former Tsarist Empire, complicated three-sided contests were in progress between the Bolsheviks, the Whites and local national movements.

Piłsudski sought in vain to form a federation of like-minded border states, so concentrated instead on securing a solid block of territory. He rebuffed the “White” General Denikin, who thought absurdly that the “Whites” could co-opt the Poles while denying them self-determination. He took control of West Ukraine (East Galicia) including Lwów, occupied both Wilno and Minsk, and sent troops across the frozen Dvina to help the Latvians.

Józef Piłsudski with soldiers of the Polish army, Wilno, April 1919 (Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe/public domain)

After a brief interval in the winter, the campaign of 1920 was to assume a totally different, ideological character. So long as the Bolsheviks were preoccupied with the Civil War, they had nothing in mind beyond their survival. But, having conquered the Russian heartland in the course of 1919, they began to heed the dictates of their ideology, which told them that the Communist Revolution should be exported from Russia to Germany, Marx’s homeland, at the first opportunity.

“The Red Bridge”

According to Marxist theory, Russia’s largely peasant society was unsuited to a genuine proletarian revolution, and most Bolshevik theorists, like Nikolai Bukharin, accepted that their movement’s long-term interests demanded a link-up with more developed countries, where a substantial industrial proletariat existed.

After long hesitations, Lenin now cast caution aside, believing that the moment had come for expansion. Trotsky, the Commissar for War, objected, knowing the Red Army’s limitations, and proposing that the first wave of revolutionary expansion should be directed against Asia, not Europe. But he was overruled. For Lenin also assumed (wrongly) that the Red Army would be welcomed by the oppressed workers and peasants along the way. In this scenario, Poland occupied the “Red Bridge” which the Red Army had to cross on the route from Russia to Germany.

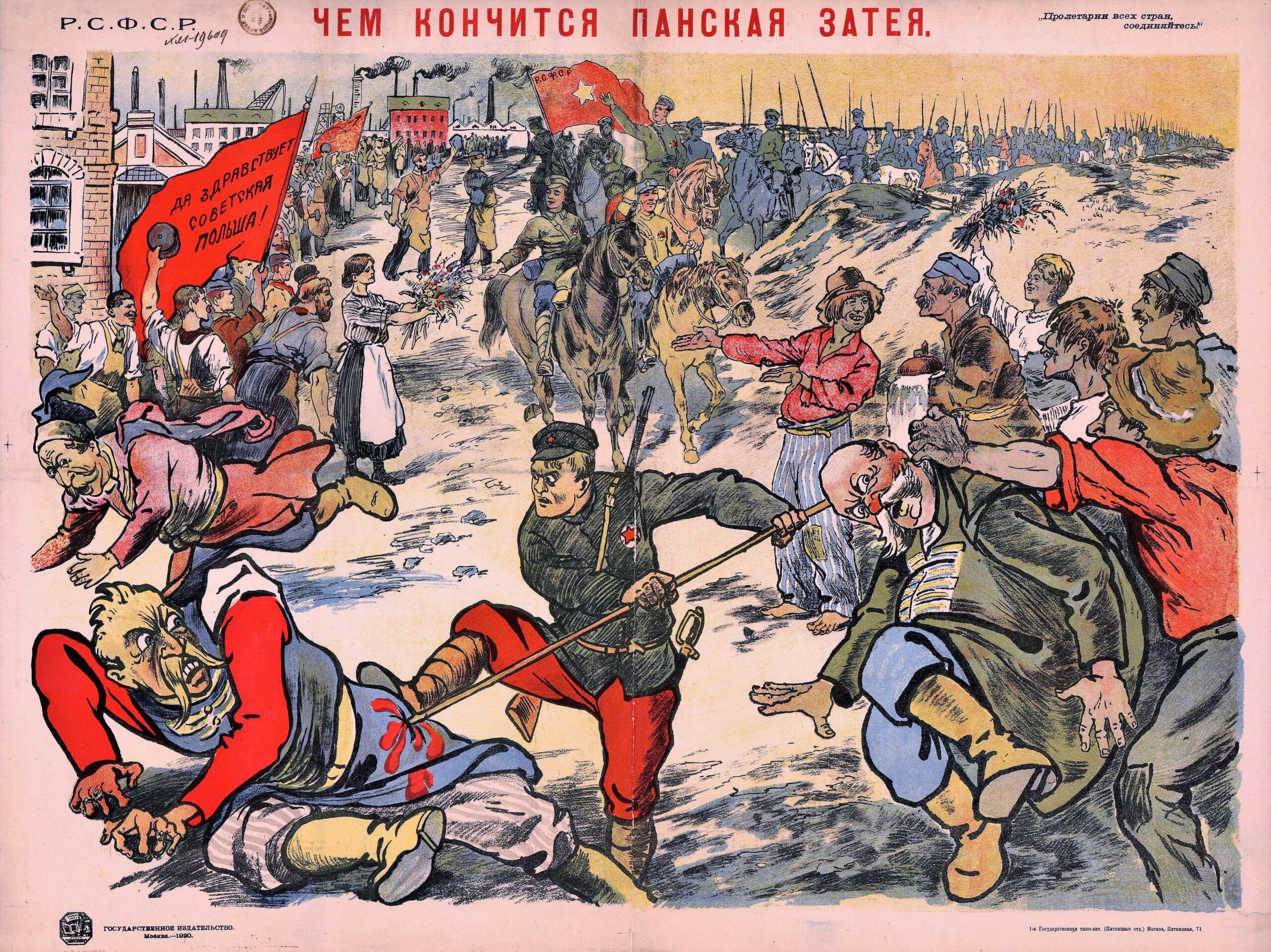

Soviet propaganda poster, 1920 (Russian State Library/public domain)

The winter of 1919-20 was a critical time. Lenin was calling loudly for peace with Poland, while blatantly building up the Red Army’s presence in Russia’s western regions. Writing about this fifty years ago, I talked about Piłsudski’s “sound instincts” in resisting Lenin’s blandishments. We now know that he was receiving detailed reports from Polish radio intelligence which provided concrete evidence of the Bolsheviks’ bad faith.

As the new campaigning season approached, Piłsudski realised that doing nothing would be fatal, and his response was twofold. Firstly, he opened an alliance with Semeon Petlura’s Ukrainian Directorate, and secondly, in the company of Petlura’s Ukrainian divisions, sought to disrupt Lenin’s preparations by moving on Bolshevik-occupied Kyiv. The Polish Army marched eastwards in late April, and within three weeks was welcomed in Kyiv with flowers.

Predictably, the Soviet propaganda machine reacted furiously, denouncing “Polish imperialism” and deluging western capitals with strikes and placards demanding “HANDS OFF RUSSIA”. As usual, western opinion misjudged the realities.

Few westerners knew that Kyiv was no longer part of Russia or that Bolshevism could be a threat to anyone. Indeed, in that imperial era, many people thought that the idea of national independence set a dangerous precedent. British trade unions followed the Communist lead, identifying Piłsudski as the aggressor and vowing to block all military supplies to Poland.

Although the Kyiv operation gained a little time, it did not go well. Ukraine was still riven by numerous armed factions, and Petlura failed to assert his overall authority. Before long, the Bolsheviks were assembling a powerful strike force led by the formidable “Konarmia” of Semyeon Budyonny, which was withdrawn from the front fighting Denikin’s “Whites”. The Polish garrison in Kyiv became increasingly isolated and decided to withdraw. As one veteran put it, “We ran all the way to Kyiv, and ran all the way back.”

Polish soldiers enter Kyiv, May 1920 (unknown author/public domain)

Bolshevik propaganda was not without effect in Poland. Although Polish society was still overwhelmingly rural, and Poland’s prime minister in 1920, Wincenty Witos, leader of the Polish People’s Party (PSL), was an archetypal peasant from Tarnów, the hostile Communist slogan of “Pan’skaya Pol’sha“, or “Poland of the Landlords”, had strong historical overtones, and resonated widely, especially among Belarusians and Ukrainians in the eastern borderlands (Kresy).

Furthermore, the Bolsheviks appealed strenuously to the large Jewish community, urging them to desert their “Polish masters”. Those appeals fell largely on deaf ears; most Polish Jews were religiously conservative, spurned right-wing Zionists and left-wing Communists alike, and remained loyal to Poland. Even so, the unfair stereotype of Żydokomuna (Judeo-Communism) took root, and the Polish army took needless precautions by interning considerable numbers of Jewish soldiers.

Red Army offensive

After some delay, the Red Army’s main offensive took off on 4 July, crossing the Berezina and heading for the “Red Bridge”. It was commanded by Mikhail Tukhachevsky, the “Red Napoleon”, a young Civil War general who now disposed of a million men. In his Order of the Day, he boasted that he would march “over the corpse of White Poland” and that his men would be “galloping through the streets of Paris before the summer was out.” The strategic plan envisaged Tukhachevsky’s larger force joining up near Warsaw with a “South-western Front” then advancing further to the south.

The Bolsheviks’ political deployment included the formation of a Polish Revolutionary Committee, the Polrevkom, under their security chief, Feliks Dzierżynski, who was designated to take over Poland’s government. They also despatched Joseph Stalin, the Commissar for Nationalities, who was to act as the supreme “Political Member” of the South-west Front. (In the Bolshevik system, no general enjoyed full command of his forces, always being subject to the supervision of a senior party member.)

Soon, the Polrevkom would seize Białystok, the first city which they recognised as Polish, while Dzierżynski would take up residence in the Wyszków plebania (presbytery), only 60 km from Warsaw. Lenin urged him to order the gratuitous murder of landowners.

Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Lenin and Mikhail Kalinin, 1919 (Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

In mid-July, as the Red Army bore down, the Polish government turned to the Allied powers for assistance. France, instead of sending troops as requested, sent General Weygand to supplement the small French Military Mission already present. Great Britain, under Lloyd George, called for an Interallied Commission to Poland to observe the unfolding events, while the British Foreign Minister, Lord Curzon, who was attending a diplomatic conference at Spa in Belgium, proposed a ceasefire, hurriedly sketching a ceasefire line to separate Polish and Soviet troops.

This line was immediately rejected; there was no ceasefire, and Lord Curzon’s line played no further role. However, Curzon’s sketch was sent to London to be forwarded by telegram to Moscow; during its overnight stay in the Foreign Office in London, it was secretly amended by a junior clerk, Lewis Namier; and twenty-three years later, at a crucial moment in the Second World War, it was resurrected by Vyacheslav Molotov, who pulled it like a rabbit from a hat and presented it to the world as “the Curzon Line”.

At the Spa Conference, Allied diplomats also gave attention to the delicate question of the Polish-Czechoslovak frontier, making a resolution in circumstances much to Poland’s disadvantage. Eighteen months earlier, the local Poles and Czechs of Cieszyn had reached an amicable agreement over the frontier’s placement, but the agreement was overthrown by French-backed Czechoslovak military action.

The Peace Conference aimed to settle the matter by a popular plebiscite. But now the plebiscite was abandoned, and an arbitrary line was drawn through the middle of Cieszyn, leaving the town square in Poland and the railway station in Czechoslovakia. Here were the seeds of the “Zaolzie Problem”, which would erupt again in 1938.

As for the Interallied Mission, one can only describe it as a wash-out. It had several distinguished members, including Marshal Ferdinand Foch, General Weygand, Jean-Jules Jusserand, a French diplomat, Sir Maurice Hankey, the British Cabinet Secretary, and Lord D’Abernon, the British Ambassador to Berlin. But it never had a chance of making a positive contribution.

Interallied Mission to Poland, 1920, with front row (from left) of Lord D’Abernon, Jean Jules Jusserand, Maxime Weygand and Maurice Hankey (Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

David Lloyd George, its originator, accepted that the loss of Poland to Bolshevism would be undesirable. Yet he had swallowed the idea that Poland was the original aggressor, that Piłsudski, as a “pro-German”, ought to be replaced, and that Bolshevik arguments were “reasonable”. He ignored the comments of his colleague, Winston Churchill, who told him bluntly: “You are on the high road to embrace Bolshevism.”

Not surprisingly, the Mission was met with a cold shoulder, and it departed before the conflict peaked. The only member who stayed on to use his time fruitfully was Lord D’Abernon. The doughty ambassador drove far out of Warsaw in his convertible Rolls Royce, “scouring the countryside for Cossacks”, learning about Poland’s war effort, and eventually writing a book entitled: The Eighteenth Most Decisive Battle of World History.

Altogether, the diplomatic corps performed feebly. Almost all the diplomats fled the capital, leaving their doyen, the Papal nuncio, Cardinal Achille Ratti, alone. Ratti, like D’Abernon, was a fearless character. He never deserted his post and condemned the Bolsheviks as the servants of Anti-Christ. (He was asked to leave Poland a few months later after making some indiscreet remarks on the intractable problems of Silesia). After a couple of years, he would emerge from the Vatican conclave as Pope Pius XI.

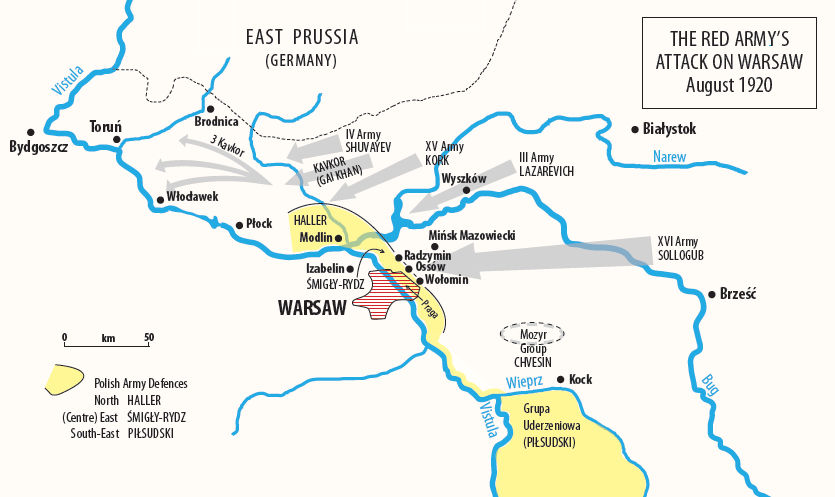

Many Polish historians assume that Tukhachevsky’s primary goal was to conquer Poland. This is not the best way of putting it. Tukhachevsky needed to subdue Poland in order to reach the objective of prime importance, which was to cross the “Red Bridge” and spread the Revolution into Germany. To this end, on reaching the River Bug, he divided his advancing columns into two separate groups.

Preparing for battle

The larger northern group consisting of three armies – the IV, XV and III Cavalry Corps – was to by-pass Warsaw, penetrate the gap between Warsaw and the East Prussian frontier, and force the Vistula bend 200 km further on in the region of Bydgoszcz-Toruń. The smaller, central group of two armies – the III & XVI – was to assault the capital directly. (Some analysts thought that the purpose of bypassing Warsaw was to wheel round beyond the capital and to attack from the West, as the Russian Army had done in 1831.)

What happened in practice was that the northern group’s spearheads led by the Kavkor of the Iranian-born Ghai Khan (Hayk Bzhishkyan 1887-1937) raced ahead, making no effort to divert to Warsaw, but riding straight for the Vistula bend, and, beyond that, for the Oder and Berlin. Some of their leading horsemen were to reach the Vistula’s left bank near Bobrowniki.

The central group, in contrast, slowed, having lost some units that failed to cross the Bug and hoping for news of Budyonny. Their lack of pace in the first fortnight of August provided the breathing space during which Warsaw’s defences could be better prepared.

In the summer of 1920, the Polish army was less than two years old, and its condition was far from ideal. Piłsudski would lament seeing soldiers preparing for battle without proper boots or weapons. Yet, despite some desperate days, things were improving.

There was a solid core of trained soldiers, who had served either in the Polish Legions or in the Russian, German or Austrian armies. There was no shortage of senior officers, especially from the Austrian service, whose training was handled by the French Military Mission, in which Charles de Gaulle was a prominent figure.

There was a regular supply of more conscripts than could be quickly trained, a substantial number of excellent cavalry regiments, a large artillery park left over from the Great War, a gendarmeria to maintain discipline and basic provision of modern matériel such as tanks, aeroplanes and armoured trains.The principal problems centred on matching ammunition to a wide variety of small arms, on translating training manuals, and adapting procedures to the use of the Polish language.

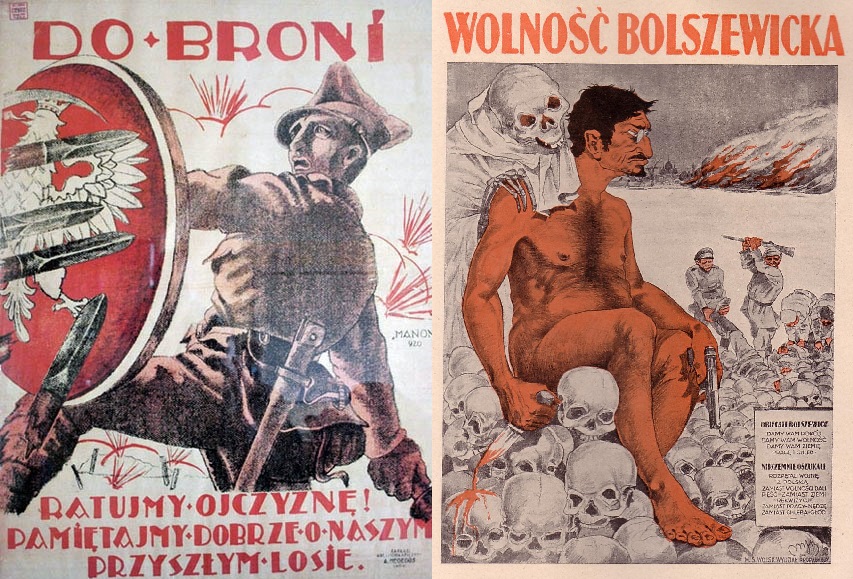

Polish propaganda posters, 1920 (Wikimedia Commons/public domain)

Critically, the Army benefited from a vast influx of volunteers, which was organised by a Council of State Defence (ROP) formed in early July. Marian Zieliński, the schoolboy volunteer from Tarnów, was but one from over 105,000 recruits placed in two months into the Armia Ochotnicza, the Volunteer Army. Most were sent on to infantry regiments, others to the cavalry, to guard battalions, to clerical duties, or to the reserves.

The varied range of volunteers included men and women, old and young, princes like Eugeniusz Sapieha or scythe-bearing peasants and humble factory workers. They were encouraged to come forward by their teachers, by the clergy and by all the political parties (except the Communists).

The Legia Akademicka, the Academic Legion, for example, was formed earlier in 1920 from students of three colleges of higher learning in Warsaw – the Politechnika, the University of Warsaw, and the Main School of Rural Economy (SGGW). It was soon transformed into the 36th Infantry Regiment, sent in May to stem the retreat from Kyiv, and deployed in August at Ossów to the east of Warsaw. Its troopers, its medical staff, its female sanitariuszki, and its chaplains like Father Ignacy Skorupka were all volunteers.

The origins of General Haller’s “Blue Army” were equally voluntary. Raised in France in 1917-18, it topped the 100,000 mark, drawing partly on Polish Americans, who sailed the Atlantic to join the colours, and partly on Polish POWs captured by the French from the German and Austrian armies. Dressed in their French uniforms, its men came to Warsaw after campaigning in 1919 in East Galicia.

Typical among them was Ludwig Marian Kazmierczak, a Polish Catholic from Poznań, a conscript to the German Army, a prisoner on the Western Front, and a volunteer, who joined the “Hallerczycy”. He was the paternal grandfather of Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The Ochotnicza Legia Kobiet (Women’s Volunteer Legion, OLK) originated in Lwów in November 1918 when it had opposed the Ukrainian takeover. Commanded by Mjr Dr Aleksandra Zagórska, the “Olki”, 2,500 strong, included female combat units in both infantry and cavalry. One of their number, Maria Wittek, would become the Polish Army’s first female general.

Female Polish soldiers training in August 1920 (Bibliothèque nationale de France/public domain)

Finally, the Kosciuszko Squadron of American aviators volunteered to serve in Poland after their service in France ended. Commanded by Major Cedric Fauntleroy and Captain Merian Cooper, they were not men of Polish origin, but were inspired by the pursuit of adventure and the wish to fight for liberty. They distinguished themselves in battles in the South against the Konarmia. After the war, Cooper became a globetrotter, a film producer, and the creator of King Kong (1933).

The defence of Warsaw was made up of three elements: North, East, and South-east. Firstly, under General Haller, defensive lines were constructed to the north of the city in the region of the old Tsarist fortress of Modlin; there the defenders, which included General Sikorski’s 5th Army, were to interrupt the passage of Tukhachevsky’s main columns.

Secondly, under General Smigły-Rydz, fortifications and trench lines were built some 20km due east of the city, beyond Praga along the Radzymin-Ossów-Wołomin line; the defenders there were to absorb the Soviets’ direct assault.

And thirdly, under Marshal Piłsudski, a Grupa Uderzeniowa, or Strike Force, 20,000 strong, was positioned on the River Wieprz, some 75 miles to the south-east.

Piłsudski, assisted by his chief-of-staff, General Rozwadowski, was the sole author of the plan. (Contrary to later myths, General Weygand played no part whatsoever.) The critical order, Nr 8358/3, was issued on the evening on 6 August. In essence, it set a trap whereby the Soviet forces would be allowed to engage near Warsaw before being hit in the flank by a killer blow.

Piłsudski experienced moments of panic, fearing the worst. Fortunately for him, he was granted an interval of almost a week during which his troops could take up position, receive supplies, and steel themselves.

Battle commences

Battle commenced at dawn on 12 August, when the Soviets pushed forward, attacking both the Praga bridgehead and the Modlin fortress. Desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued for three days. The front line swayed back and forth.

On the 13th and 14th, the Polish defences seemed to be crumbling. Radzymin was lost. Several units, including the Academic Legion, suffered terrible losses. Father Skorupka was shot through the head as he administered the last rites to a dying soldier. General Sikorski’s force at Modlin was all but overwhelmed by the weight of three Soviet armies. The 27th Infantry Division of the Red Army reached the village of Izabelin, only 13 km from the city centre. In the south, the defenders of Lwów were subject to the frenzied assaults of the Konarmia.

Polish infantry during the Battle of Warsaw, August 1920 (Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe/public domain)

Then the Poles rallied. Sikorski worked wonders, fighting off superior numbers to advance beyond the River Wkra. Radzymin was retaken, and the frontlines stabilised. The perimeter of Lwów held.

Finally, on 15 August, as Polish civilians prayed in their churches, Piłsudski was ready to strike. He must have been surprised at the ease of his plan’s execution. Fully exploiting the element of surprise, his troops thrust forward at full speed and with great energy, slicing each day through successive Soviet columns, rupturing their lines of communication, sowing confusion, and eventually causing a general rout.

At his headquarters in Mińsk Mazowiecki, Tukhachevsky was still issuing orders for the capture of Warsaw when he belatedly realised that all was lost. On the 18th, he sounded the general retreat, recalling the divisions that had marched beyond Warsaw, and initiating damage control measures.

The Soviet avant-garde of Ghai Khan now tried to cut its way back eastwards through the Polish lines – where Marian Zieliński and the Siberian Brigade lay in wait – but 30-40,000 were forced to flee across the Prussian frontier into internment. Over 10,000 were killed, and perhaps ten times that number taken prisoner.

Soviet prisoners taken near Radzymin, August 1920 (Archiwa Państwowe/public domain)

Of Tukhachevsky’s five armies only the XVI, remained intact. The rest were streaming back in disorder to whence they came. The Polrevkom disappeared, never to be seen again. Dzierżynski slinked home to resume his murderous activities in Moscow. Stalin faced Trotsky’s wrath, and a disciplinary hearing at a Party tribunal.

The Polish pursuit continued for the following seven weeks, driving the frontline deep into Belarus. Two major battles were fought – one at the end of August at Komarow, in the so-called “Zamość Ring”, the biggest cavalry battle of the war, where the Konarmia was cornered, battered, and driven off for good, and the other in late September on the River Niemen, where the Red Army attempted to make a stand. By then, Lenin had lost the “infantile enthusiasm”, for which he berated his comrades, eager to forget his ideological experiment.

The war of 1920 generated several works of literature. On the Polish side, Stefan Żeromski’s novel, Na probowstwie w Wyszkowie (1930), explored the psychology of Dzierżynski’s interplay with his hosts in a Polish village.

On the Russian side, Izaak Babel’s beautifully written Konarmia Stories (1926) re-constructs the euphoria, cruelty, and romance of Budyonny’s Red Cavalry. Many readers take the stories to be a documentary record – which they are not. But they are the only version of events, which most westerners know.

Polish cavalry, Battle of the Niemen River, September 1920 (Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe/public domain)

The poet Wladyslaw Broniewski (1897-1962), a lifelong political leftist, distinguished himself as a young soldier in the Polish Legions, the Polish-Soviet War, and later in the Anders Army. Thirty years later he would compose some embarrassing poems about Stalin. But the genuine feelings behind his definition of the “Bolshevik War”, as his Pamiętnik records, are hard to fault:

The Sovdepia (Soviet Russia) has unleashed all its forces against Poland. Hordes of Russians, half-wild Bashkirs and Chinese are throwing themselves against us under the slogan of “Death to Poland”. It is a struggle of two nations – of fire and water – a struggle between the ideas of nationhood and of predatory expansionism, irrespective of whether they [shout] “Unify the Slavs” or “Unite the Proletariat”..

Causes and consequences

Poland’s victory may be attributed to the superior morale of people defending their homeland, to the successful marshalling of limited resources, to the perfect timing of Pilsudski’s counterattack and, of course, to Soviet mistakes.

The Red Army’s defeat can be explained by several factors. One obvious cause was the Soviet command’s complacent underestimation of Polish capabilities. A second, as shown by the lamentable condition of many Soviet POWs, lay in the poor training and motivation of all but the elite units; Tukhachevsky had the numbers but not the quality in the rank-and-file. A third centred on the failure of Stalin’s “South-west Front” to link up with Tukhachevsky; if the Konarmia had ridden hard for Warsaw, instead of attacking Lwów, it would probably have disrupted Piłsudski’s assembly points on the Wieprz.

Above all, one has to recognise the deep delusions which always underlay the Bolsheviks’ programme, which could only have been achieved by coercion. It was simply untrue that the European masses were longing for the future promised by Communism. And it was simply untrue that the peasants, workers, and Jews of Poland, despite all their acute problems, had any great sympathy for Lenin’s dreams.

As for the consequences, it is certain that the Battle of Warsaw exerted a huge impact on interwar Europe. It indefinitely postponed the Bolsheviks’ hopes of spreading their Revolution, and changed their strategic priorities, forcing them to concentrate on Soviet Russia’s internal issues, on the New Economic Policy, and on the formation of the Soviet Union under the slogan of “Socialism in One Country”.

It also secured not only Poland’s independence but the freedom of all the other countries of the region, which would have been greatly threatened by a Soviet victory. It saved Germany from its first potential clash with Communism and it gave the Western Powers an opportunity (which they squandered) of strengthening benign democratic influence in Eastern Europe.

Ceremony presenting Józef Piłsudski with the marshal’s mace, November 1920 (Narodowe Centrum Cyfrowe/public domain)

On the downside, the Battle of Warsaw helped foster the crisis in the Bolshevik camp, from which Stalin would emerge triumphant, using Lenin’s legacy as a springboard for consolidating the world’s first, large-scale totalitarian tyranny.

Stalin never forgot 1920. When he came to organise a series of show trials, in which the surviving Bolshevik leaders were judiciously murdered, the very first of his victims was Mikhail Tukhachevsky; and all the men who signed Tukhachevsky’s death warrant had been Stalin’s immediate comrades in the Political Council of the South-west Front 16 years earlier.

One must say, too, with regret, that the Battle of Warsaw has contributed to the paranoic mythology that pervades most Russian views of the past. Russians know virtually nothing about 1920. All they hear is what Bolshevik propaganda invented, namely that innocent Russia had been viciously attacked. In this twisted scenario, Piłsudski becomes a partner for Denikin, Yudenich and Kolchak, and all the warmongering “puppets of Western imperialism”, and a predecessor of Adolf Hitler, who copied them in 1941.

I have seen this paranoia with my own eyes. In the early 1990s, I was invited by the British Ambassador in Moscow to present a lecture on the history of Britain’s relations with Russia and Poland. I closed with an explanation of how Messrs Gorbachev and Yeltsin had admitted to the mass murder of 20,000 Polish officers by the NKVD in the Katyn Forest massacres of 1940. Before I knew it, a man began handing out leaflets which claimed that 60,000 Russians had been murdered by Poles in the POW camps of 1920.

All of which shows that the reckoning goes on from generation to generation. In the last resort, however, Poles can take pride in the events of 1920. Nowadays, they hope that the era of national hatreds and bloodletting is over. Yet they know, too, that truth was on their side, and Poland defended itself against Bolshevism in a just cause.

Despite the pain, the ordeal strengthened their self-esteem and sense of identity after long decades of foreign oppression and helped them survive still greater horrors in future decades.

Norman Davies is UNESCO Professor at the Jagiellonian University, Professor Emeritus at University College London and senior consultant to the Notes from Poland Foundation. He is the founder of the Project for Polish Studies Abroad, which aims to assist the development of Poland-centred studies at university level in countries outside Poland through the Fundacja Normana Daviesa.

Main image credit: Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe (under public domain)