Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Zula Rabikowska

One of Poland’s most remarkable photographers, Zofia Rydet, was in her lifetime largely unrecognised on both the domestic and international stage.

That has since changed, and her first major solo exhibition in the UK presents Rydet’s monumental project, Sociological Record, in which she ambitiously documented the homes and people of Poland in more than 20,000 images taken between 1978 and 1997, the year of her death.

For British audiences, the exhibition serves not just as an introduction to Rydet herself and to the shifting realities of Polish history, but to a body of work that reimagined what photography could do – establishing what Rydek herself called “sociological photography”.

Early life and work

Rydet was born in 1911 in Stanisławów, a town that belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time, later becoming part of Poland when it regained independence in 1918, and is now Ivano-Frankivsk in Ukraine.

The upheaval of her early life – in particular the Second World War and her family’s forced displacement westwards amid postwar border changes – meant that Rydet came to photography relatively late in life, publishing her first series when she was in her 40s.

At a time when both Poland and the international art world were overwhelmingly dominated by men, she pursued photography with unusual intensity and independence.

While many of her contemporaries aligned with state institutions or international salons, Rydet operated largely outside the mainstream, building a body of work that was both deeply personal and sharply observational.

Trained initially by her older brother – Tadeusz Rydet, a photographer known for his portraits of the Hutsul highlanders – she began taking pictures in the late 1930s, but only began to seriously pursue the medium after the Second World War.

In the 1950s, she took part in amateur photography competitions, gradually building recognition that culminated in her first book, Little Man, published in 1965.

It focused on children, exploring childhood, motherhood, and old age, using photographs taken in Poland as well as during her travels to Albania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Egypt, Lebanon, and Czechoslovakia.

Zofia Rydet: Dokumentacje 1950-1978 | Życie codzienne na kieleckiej wsi. Huta Szklana (w woj. kieleckim), 1974 r. pic.twitter.com/XSLPfNqNQm

— Fotoarchiwum_PAP (@paparchfoto) November 4, 2025

Little Man laid the groundwork for Sociological Record, both methodologically and thematically. Her careful attention to the gestures, spaces, and social interactions of her subjects would later expand to a broader examination of entire households and communities in Poland.

The humanist sensibility — the desire to document life with empathy and psychological insight — remained central throughout her career, whether in the intimate worlds of children or the complex domestic lives of adults across the country.

Early on, Rydet experimented with photomontage, exploring subjects from a distinctly female perspective – maternity, relationships between women, and the lingering trauma of war.

The photomontages and collages Rydet created in the 1950s and 1960s explored the female body, motherhood, female friendships, and the lived experience of women in Poland. These early works were highly constructed, intimate and often surreal, reflecting not only her personal vision but also a broader interest in women’s emotional and social lives.

Sociological Record

But it was in 1978, at the age of 67, that she embarked on the work that would define her legacy, Sociological Record, making her one of Poland’s most significant chroniclers of everyday life.

Over the following decades, Rydet produced an extraordinary archive of more than 20,000 images, systematically photographing people in their homes across towns and villages in Poland.

Sociological Record adopted a more systematic, documentary approach – photographing households and communities across decades and regions – than her earlier work, yet the underlying sensibility remained consistent. The careful attention to domestic interiors, gestures and personal objects can be seen as an extension of her interest in women’s private worlds.

Although the project includes men and families, a notable focus on women emerges: they appear on doorsteps, in kitchens, and amid the intimate routines of daily life, carrying forward Rydet’s enduring curiosity about female subjectivity, agency and social roles.

One particularly poignant photograph shows a woman seated on a simple chair beside a bare table, where a wedding portrait of a young couple is carefully displayed. Behind her, another photograph of an older couple hangs on the wall — perhaps her parents or herself many years earlier.

The woman’s expression is not serene but marked by fatigue and quiet dejection; her plain clothing and the sparse interior speak of poverty and the passage of time. The contrast between her present condition and the idealised wedding image beside her creates a silent tension — between hope and disillusionment, youth and age, private dreams and collective circumstance.

In this way, the photograph captures how Sociological Record transforms the domestic space into a site of social truth, where the endurance of women becomes both a personal and historical document.

In this sense, Sociological Record can be read not simply as a sociological survey but as a continuation of Rydet’s exploration of women’s experiences, now reframed within the broader structures of Polish society.

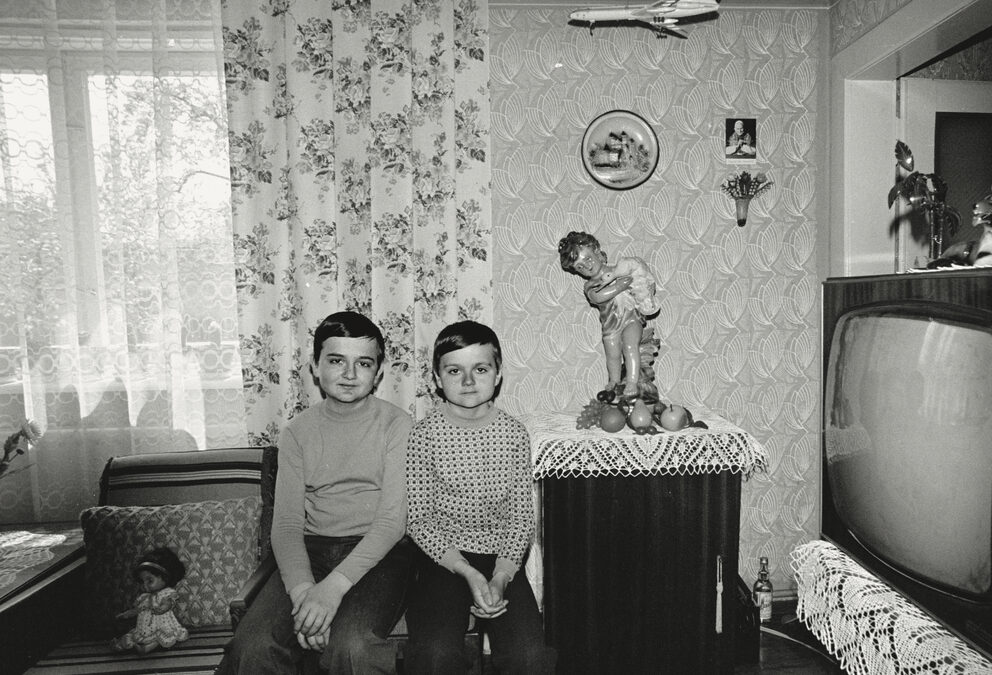

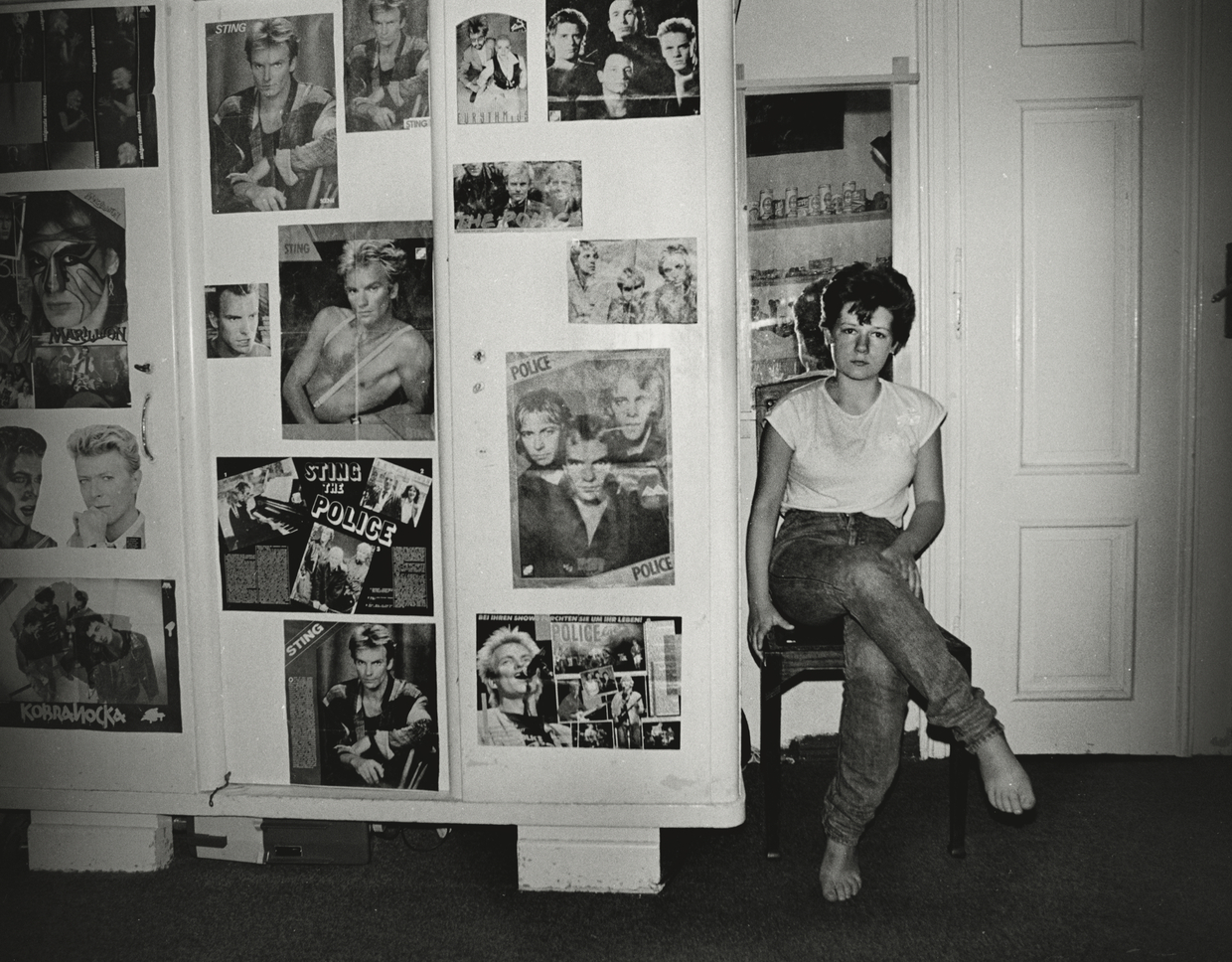

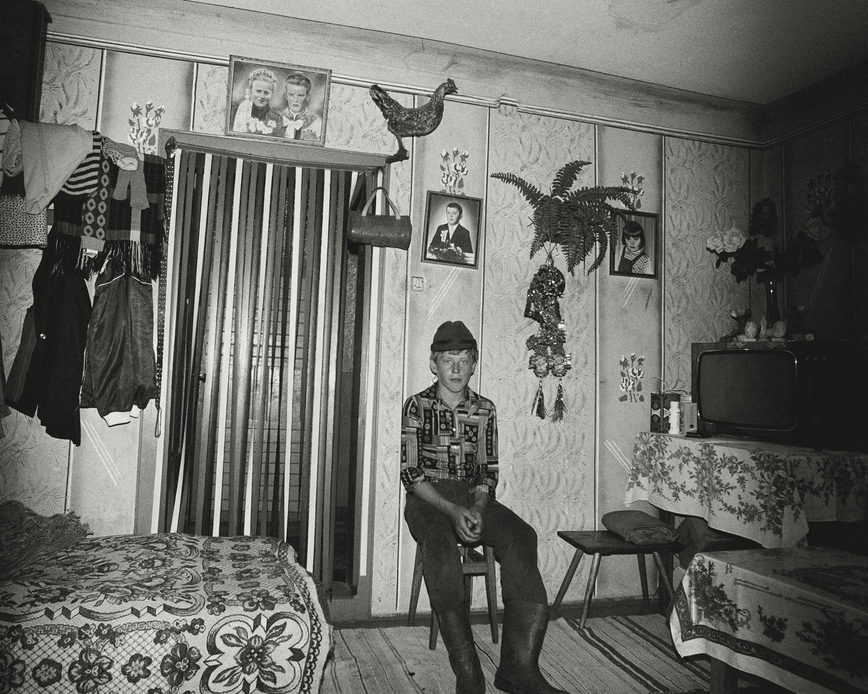

What makes Sociological Record exceptional is not simply its scale, but its method. Rydet imposed a strict formal consistency: her subjects posed in their domestic interiors, surrounded by their possessions, often looking directly into the lens.

This uniformity stripped away the photographer’s aesthetic ego and placed emphasis on the subjects themselves – their gestures, furnishings, religious icons, and everyday objects that together form a collective portrait of a nation on the cusp of modern transformation.

One striking example is a black-and-white photograph of a young woman seated beside a wardrobe plastered with posters of Sting and his rock band The Police. The room is modest, its sparse furniture and plain walls offset by these vivid emblems of Western popular culture.

Her calm, direct gaze evokes both self-possession and quiet yearning, situating her between two worlds — the residual austerity of communist Poland and the seductive promises of global modernity.

In this image, Rydet captures not just a person, but a generational tension: the desire for individuality and freedom emerging within a constrained social and political landscape.

Rydet was “driven by a desire to document people and a reality that was disappearing”, notes Łukasz Gorczyca, a gallerist who holds some of the photographer’s original prints in Warsaw. This impulse led her across Polish villages, where she would knock on doors and ask to photograph people in their homes.

In this sense, Rydet’s project was both profoundly Polish and universally resonant. It captured the final years of a rural, pre-capitalist world before it was irrevocably altered by late socialism, migration and globalisation. It also asserted the political and cultural significance of domestic space, particularly as seen through the eyes of a woman photographer.

One telling example is a black-and-white photograph of a young man seated in a modest room containing a table, a bed and a television. The walls are decorated with family photographs and other personal objects, creating a layered portrait of private life.

Through this image, Rydet highlights how domestic interiors reflect broader social and cultural dynamics — the presence of the television signals the presence of modernity, while the photographs and ephemera evoke memory, continuity, and local identity.

Rydet positions the home itself as a microcosm of societal change, revealing the intersections of personal experience, generational shifts, and national transformation.

Rydet’s achievement lay not only in documenting but in reconfiguring how documentary could function. Sociological Record foregrounded intimacy, repetition and accumulation as strategies of truth-telling. The project can be read as a counternarrative to both the heroic myths of socialist realism and the romantic notions of Polish identity. Instead, it presents the everyday as a site of complexity, dignity and change.

Rydet’s legacy

Rydet’s legacy is still being reckoned with. Her recognition in Poland is a poignant narrative of artistic perseverance and gendered marginalisation.

Despite her extensive body of work, Rydet was often regarded as an outsider within the Polish photographic community, which was predominantly male and urban-centric. Her earlier works were considered sentimental and kitschy by some critics, leading to limited recognition during her lifetime

It was only posthumously that Rydet’s contributions gained the acclaim they deserved. In 2015, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw held a comprehensive exhibition of Sociological Record.

This exhibition marked a significant turning point in acknowledging her work’s artistic and historical value. Subsequent exhibitions at institutions like Jeu de Paume in Paris and now The Photographers’ Gallery in London have further solidified her status as a pioneering figure in 20th-century photography.

Internationally, her work is increasingly being recognised alongside the likes of August Sander or Diane Arbus – not as a derivative figure, but as someone who independently developed a systematic, radical mode of portraiture.

Happy birthday, Zofia Rydet! The photography icon would be 105 today: https://t.co/e1GK4HHL31 pic.twitter.com/BlBFOtRV9j

— Culture.pl (@culture_pl) May 5, 2016

Clare Grafik and Karol Hordziej, who curated the exhibition at the Photographer’s Gallery, say that, in terms of the visibility of women artists from Central and Eastern Europe in the UK, it seems a very good moment to (re)discover women artists from less represented parts of the globe and to present them in western Europe or the US.

They highlight that, for many years, there has been less interest or knowledge around these practices so it is important to redress this balance.

Today, Sociological Record feels prescient: in an era of data, archives and digital image saturation, Rydet’s obsessive, almost algorithmic approach resonates with new urgency.

Rydet once said that she was motivated by a fear that people and things are passing, that everything is vanishing. What she left behind is not just a record of a disappearing Poland, but a body of work that continues to challenge how we see ourselves, our homes, and our histories.

Zofia Rydet: Sociological Record is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London from 10 October 2025 to 22 February 2026.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Image credits: © Zofia Rydet, courtesy of the Zofia Rydet Foundation, via The Photographers’ Gallery