Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Adam Musiał

The above photo, of men in white-eagle jerseys, shows Poland’s men’s national football team. It was taken on 28 May 1922, before the squad’s third international match, against Sweden, three-and-a-half years after Poland’s reappearance on the political map of Europe.

Among the men pictured in the photo are three Jews from Kraków, Józef Klotz, Leon Sperling and Józef Lustgarten, who participated in a historic event not widely known to Polish fans: the first goal scored for the men’s national team.

Klotz, Sperling and Lustgarten came from backgrounds that reflect the diversity of the Jewish community in Kraków during the interwar years. Their different wartime trajectories also mirrored the fates of many other Polish Jews during World War Two.

The match

Held in Stockholm, the 28 May 1922 football match was only the third international game played by the Polish national team. The team’s debut game took place in December 1921 against Hungary in Budapest.

Poland lost the match to Hungary 1–0. The Hungarians came to Kraków for a rematch on 14 May 1922, and defeated Poland again, with a score of 3–0.

The front page of Tygodnik Sportowy, a sports weekly, after Poland’s first international match against Hungary (image credit: Biblioteka Jagiellońska)

Two weeks later, the Polish team travelled to Stockholm for its match against the favoured Swedish team. The Polish squad included Sperling and Klotz and was coached by Lustgarten, a former goalkeeper, referee, and member of the Polish Football Association.

Twenty-seven minutes into the match, the Polish team launched an attack by Sperling, which resulted in a penalty kick against Sweden. The Polish sports paper Przegląd Sportowy (Sports Review) later described the moment:

[…] Klotz, composedly and unhurriedly, sends the ball into the top left corner just below the bar. The goalkeeper does not even budge. With this, the Polish national team score their first goal in the history of their international games.

Poland ended up winning the match 2–1.

Jewish football clubs

Józef Klotz and Leon Sperling began their football careers playing for a Jewish football club. During the interwar period, both Jewish and non-Jewish football clubs proliferated.

The name of a club often indicated its political, professional or social affiliation – a phenomenon that seemed more common among Jewish clubs than non-Jewish clubs, but it also occurred among the latter.

The author Henryk Vogler wrote about Jewish football clubs in his memoir, Wyznanie mojżeszowe. Wspomnienia z utraconego czasu (Mosaic Faith: Memories from a Lost Time). Contrasting Jutrzenka Kraków and Makkabi Kraków, he explained, “Jutrzenka was a club of assimilated and working-class youth, while Makkabi was popular with Zionist youth, and hence the mutual hostility also in the domain of sports”.

Józef Klotz: the scorer

Józef Klotz, who scored the first international goal for Poland, was born in Kraków on 2 January 1900, to Markus, a tailor, and his wife, Salomea. Markus and Salomea had five children: Józef, who was the eldest, followed by Jan, Genia, Samek and Maniek (Mosze).

2.01.1900 urodził się JÓZEF KLOTZ

⚽️Piłkarz,reprezentant Polski-strzelił pierwszego gola w historii reprezentacji

⚔️Żołnierz Legionów,wojny pol-bol

1940-zamknięty w getcie w Warszawie

✝️Rozstrzelany przez Niemców w ulicznej egzekucji po łapance w wieku 41 lat.

Cześć Jego pamięci! pic.twitter.com/sm79RoC6Ho— Fundacja im. Janusza Kurtyki (@FundacjaKurtyki) January 2, 2021

To learn more about Józef’s family and upbringing, I contacted his nephew, Danny Dekel (Samek’s son), who was born just after the war and is now living in Israel. Dekel described the Klotz family as living a secular, acculturated lifestyle:

They spoke Polish at home, not Yiddish. Grandparents Markus and Salomea also knew German. The Klotzes were not Zionists. They regarded Poland as their homeland, and it was in Poland that they saw their future. Neither were they a very pious family. They’d only go to synagogue on Yom Kippur.

The Klotz children were very fond of sports. Józef, Jan and Samek all played football for Jutrzenka Kraków. Given the liberal character of the Klotzes’ home, Jutrzenka, rather than its biggest local rival, Makkabi, seemed a natural choice for the three sports-loving brothers.

At about six feet (185 cm) tall with a good physique, Józef played as a defender. He played for Jutrzenka until 1925, when he moved to the Polish capital and played for Makabi Warszawa, Jutrzenka’s ideological opponents.

According to Dekel, Józef moved to Warsaw for his future wife, with whom he had a daughter, born, Dekel believed, between 1936 and 1939. Only a few years later, in 1941, Józef died in the Warsaw Ghetto. Dekel did not know exactly how his uncle died or what happened to his wife and daughter.

Leon “Munio” Sperling: Ball Wizard

It was Leon Sperling’s dash along the left wing that set up the penalty kick that resulted in the historic goal for Poland in the match against Sweden.

Sperling was born in Kraków on 7 August 1900. In 1914, like Klotz, Sperling started his football career playing for the Jewish football club Jutrzenka.

In 1920, he moved to the all-Kraków team Cracovia, for which he played 381 matches. Unlike Wisła, another big Kraków team, which did not accept Jews, Cracovia took whoever was good enough to play and usually had one or two Jewish players on its squad.

Sperling was one of the best players of the interwar period. His excellent technique and masterly dribbling skills earned him the nickname “Ball Wizard”. He played for the Polish national team 16 times, scoring two goals, and took part in the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris.

In 1931, Sperling was awarded the Silver Cross of Merit by Prime Minister Walery Sławek in recognition of his contribution to the development of Polish sports. Sperling’s skill made him a popular icon and a hero for young fans.

After the outbreak of World War Two in September 1939, Sperling fled from Kraków to Lwów with his wife, who was originally from former eastern Galicia. Like many other Polish Jews at the time, Sperling chose the Soviet invasion of eastern Poland, rather than the Nazi occupation, as the lesser of two evils.

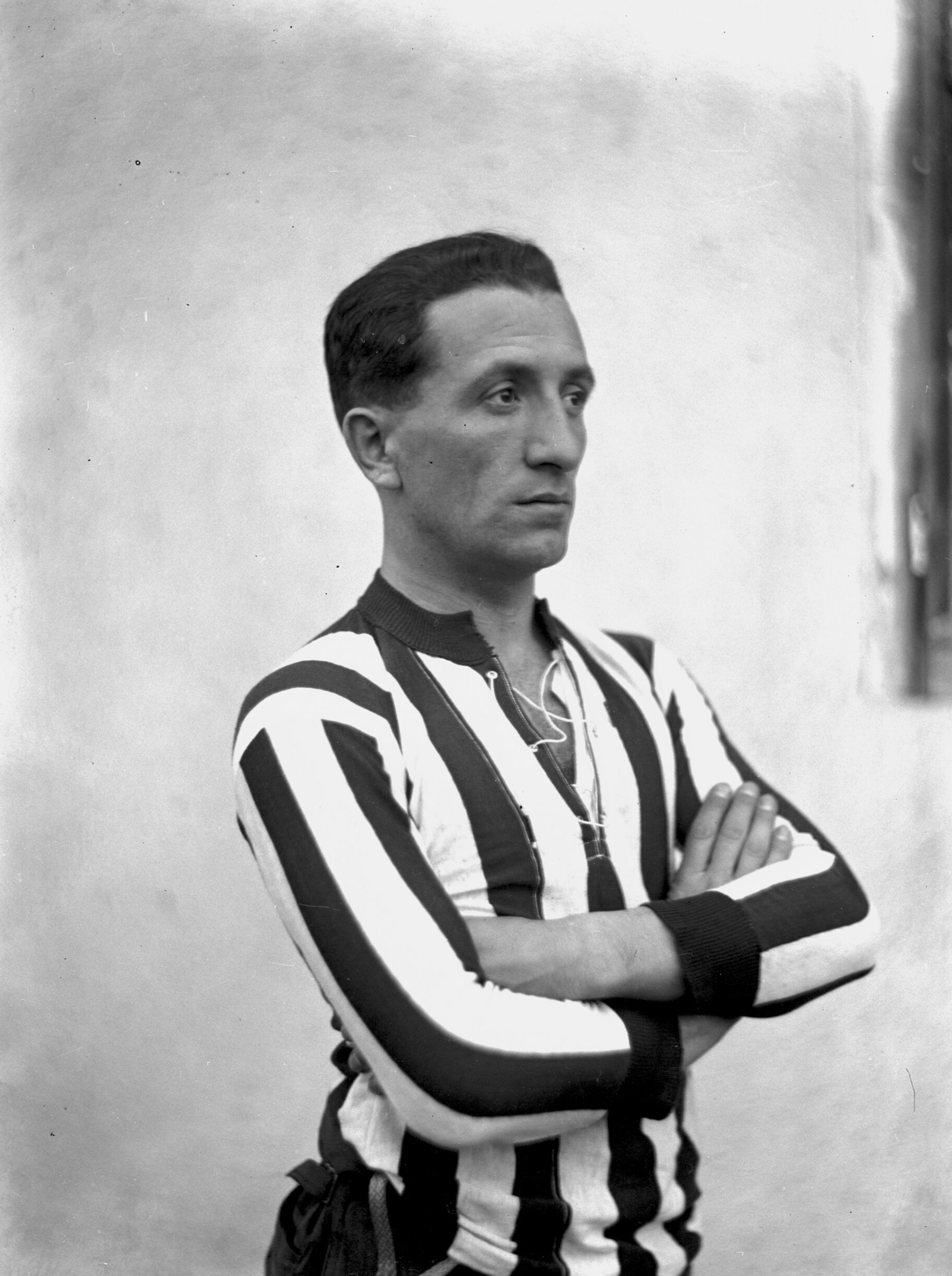

Leon Sperling, 1932

For two years, he coached a football team in Lwów. Yet after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, he ended up in the Lwów Ghetto, with thousands of other Jews, where he was shot dead by a drunken member of the Gestapo in December 1941.

Józef Lustgarten: the coach

Coach Józef Lustgarten was born in Kraków on 1 November 1889. The son of a merchant, Lustgarten studied law in Kraków and Vienna and completed his judicial training in the Austrian capital.

During World War One, he fought in the 2nd Brigade of the Polish Legions, a unit of the Austro-Hungarian Army manned by Austrian Poles. After the war, he completed his PhD in law in Kraków and worked as a clerk and a solicitor.

Lustgarten played for the football team Cracovia from 1906 to 1911. He usually played as the team’s goalkeeper but, on a couple occasions, also played as a forward.

In a book about Cracovia and its Jewish footballers, Maciej Kozłowski wrote of Lustgarten: “He considered himself both Jewish and Polish. When filling in his personal form at the Jagiellonian University in 1913, he declared to be of Jewish faith and Polish nationality”.

During his time in Vienna from 1911 to 1912, Lustgarten became a licensed football referee. After returning to Kraków, he took up coaching his beloved team, Cracovia, and started refereeing football matches.

Lustgarten coached the Polish national team in several matches in 1922. He also cowrote the Polish Football Association’s charter and served as the association’s honorary secretary. He received two national awards for his achievements: the Medal of Independence and the Gold Cross of Merit.

#TegoDnia #PiłkarskieRocznice

1 listopada 1889 roku urodził się Józef Lustgarten, były polski piłkarz, selekcjoner reprezentacji Polski, a także sędzia międzynarodowy. Całą przygodę na boisku spędził w Cracovii.Był drugim w historii selekcjonerem, po Józefie Szkolnikowskim,… pic.twitter.com/s9ILFyR9Yc

— Retro Futbol.pl (@retrofutbol_pl) November 1, 2024

Lustgarten was the only one of the three men discussed in this article to survive World War Two. Like Sperling, he managed to leave Kraków after the outbreak of the war, making his way to Lwów. At the end of 1939, however, he was arrested by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police and internal security agency.

Released in 1941 in the wake of the signing of the Sikorski-Maisky agreement, Lustgarten ended up in the Siberian city of Novosibirsk. As a popular footballer and widely respected activist, he was appointed as a delegate of the Polish government-in-exile. Equipped with a diplomatic passport, he was entrusted with assisting the Poles who had been deported by the Soviets to Siberia in 1940 and 1941.

However, the relationship between the USSR and the Polish government-in-exile was short-lived. In 1943, the Soviets broke off these ties after the Germans discovered mass graves in the Katyn forest and the Poles demanded a Red Cross investigation.

As it turned out, the Soviets had executed thousands of members of the Polish military and intelligentsia in the forest in 1940. Meanwhile, given the strained diplomatic situation, many of the Poles who had not managed to leave the USSR with General Anders’ Army were arrested, including Lustgarten.

Officially accused of anti-Soviet propaganda, Lustgarten was sentenced to ten years in the Gulag and incarcerated in the Vorkuta Corrective Labour Camp.

He returned to Kraków in 1956, never able to officially discuss his Soviet “adventure”. Back in Poland, he resumed his activities for Cracovia and the Polish Football Association. Lustgarten died in Kraków on 21 September 1973, and was buried, not at the Jewish Cemetery, but at the municipal Rakowicki Cemetery.

Conclusion

Despite their football fame, Klotz, Sperling and Lustgarten suffered the same fate as many other Polish Jews during World War Two. The members of these Jewish communities differed in the languages they used, their approaches to religion, and their social backgrounds and political views. Given the scope of this rich diversity, the void left by its brutal obliteration is especially acute.

Traitor or legend? How one Poland’s greatest footballers ended up playing for Nazi Germany https://t.co/mJHWoLW2V6

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 7, 2025

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Unless otherwise noted, all images via Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe (NAC) and under public domain.

Editor’s note: All translations in this article of text from Polish publications are the work of the author.

This article has been adapted from an article in the December 2024 issue of The Galitzianer and appears here with permission from Gesher Galicia. The Galitzianer is a membership benefit of Gesher Galicia. For more information, go to www.geshergalicia.org.

Main image credit: Sport. Tygodnik Ilustrowany. Collage created by Alicja Ptak