Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Youth unemployment in Poland has risen by more than in any other European Union country over the last year. However, its youth unemployment rate still remains below the EU average, while overall unemployment is among the lowest in the bloc.

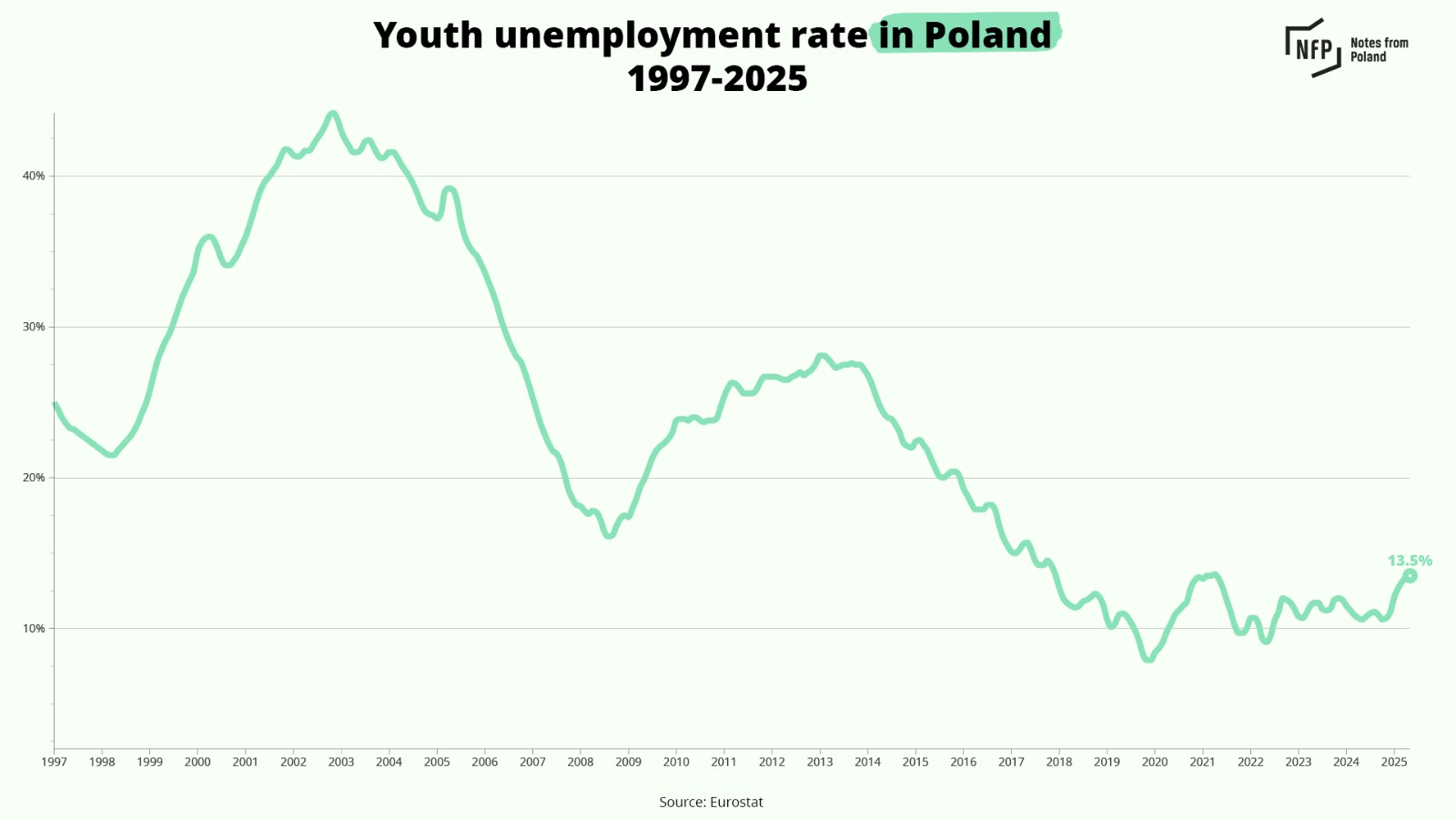

The latest data from Eurostat show that, in May, the unemployment rate for people aged under 25 in Poland stood at 13.5%, up from 10.6% a year earlier.

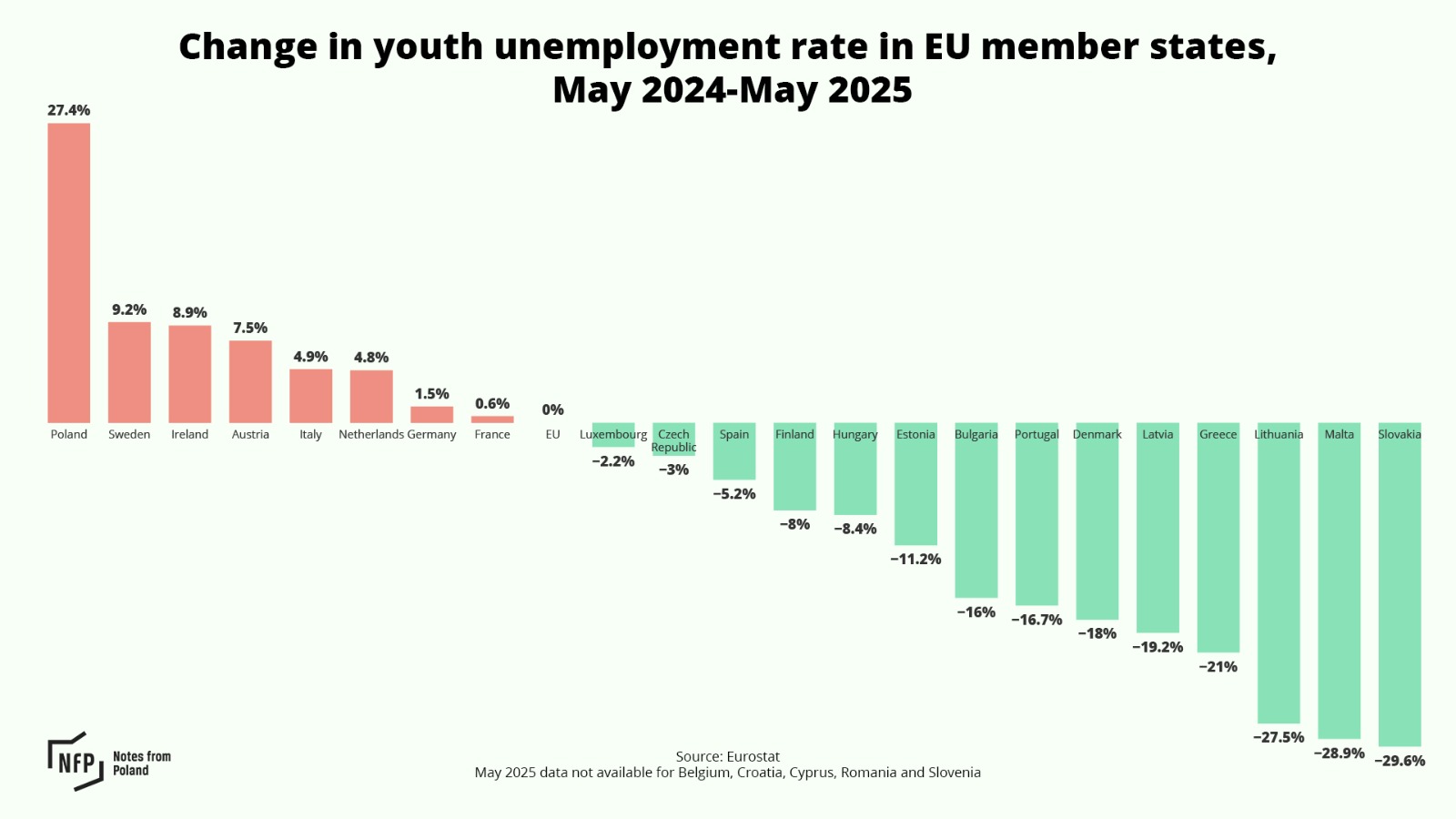

That meant the rate increased by 27.4%, much more than the next biggest annual rises, recorded in Sweden (9.2%), Ireland (8.9%) and Austria (7.5%). In terms of percentage-point increase, Poland’s 2.9 p.p. jump was also the largest, ahead of Sweden (2.1 p.p.), Italy (1 p.p.) and Ireland (0.9 p.p.).

Fifteen of the 22 countries for which data are available saw youth unemployment fall between May 2024 and May 2025, with the biggest declines in Slovakia, Malta, Lithuania and Greece.

Across the EU as a whole, youth unemployment remained unchanged, at 14.8% in both May 2024 and May 2025. That means that, despite Poland’s rapid rise in youth unemployment, it rate of 13.5% remains below the EU-wide figure.

The highest youth unemployment rates are in Spain (25.4%), Sweden (24.9%), Luxembourg (21.9%) and Italy (21.6%). The lowest are in Malta (5.9%), Germany (6.6%), the Netherlands (8.8%) and the Czech Republic (9.7%).

Poland’s rate still remains relatively low by its own historical standards, too. Youth unemployment peaked at around 44% in 2002 before rapidly declining after Poland’s entry to the EU in 2004. It then rose again from 2008 amid the global financial crisis, reaching around 28% in 2013 before again declining.

The last time youth unemployment was at similar levels to now was during the Covid-19 pandemic, when it stood above 13% during the first half of 2021.

Meanwhile, overall unemployment remains low in Poland. In January, it hit the lowest level ever recorded by Eurostat, at 2.6%, which was also the joint lowest among EU member states. By May this had risen to 3.3%, which was still the second-lowest level in the bloc.

Rising youth unemployment in Poland is in part down to a broader economic slowdown, including in Poland’s key trading partners, according to Piotr Skierkowski of ManpowerGroup, a leading global workforce solutions company with a presence in Poland.

“It is also influenced by increasing automation and digitalisation, which are reducing the number of entry-level positions, which were previously the natural entry point for young people into the job market,” Skierkowski told financial news website Bankier.pl.

“However, the biggest challenge is the mismatch between the requirements and expectations of both employers and young employees,” he added. “This applies to both salary levels and the way they work and the tasks to be completed.”

Only 5.9% Polish firms use AI tools, which is the second-lowest figure in the EU. In some member states, the number is over 25%.

"Changing this should be a priority" to avoid "losing market share to foreign competitors", writes @PIE_NET_PL in a new report https://t.co/HFcCcCmF2E

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 3, 2025

Zuzanna Ilków of Useme, a platform for freelancers, told Bankier.pl that “many tasks typical for junior staff are now being taken over by AI tools”. She also believes that the education system “still rarely develops practical skills and doesn’t prepare them for project or team work”, both of which are increasingly necessary.

Meanwhile, Krzysztof Inglot, founder of employment agency Personnel Service, notes that young people now face growing “competition from workers from other countries”. Poland has experienced record levels of immigration in recent years.

Poland’s recent presidential election saw record turnout of 76.3% among the youngest voters, aged 18 to 29. The most popular candidates among them were those at the far-right and left-wing ends of the political spectrum, whose campaigns had focused in particular on economic and social issues important to young people.

Over half of voters aged 18 to 29 supported candidates of the far right and left in the first round of Poland's presidential election.

We spoke with young voters and experts to find out what is behind this rejection of the political mainstream https://t.co/ebCGHhAcFN

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 30, 2025

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Brooke Cagle/Unsplash

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.