Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Krzysztof Mularczyk

OPINION

Poland’s rule-of-law crisis took a new, bizarre twist last week when the chief justice of the Constitutional Tribunal (TK), Bogdan Święczkowski, announced an investigation into Prime Minister Donald Tusk and other senior officials from the ruling coalition, who he says are guilty of operating as an “organised criminal group” in order to mount a “coup d’état”.

Tusk literally laughed off the accusation, posting a film of himself playing ping pong, which he said was “more important”. He and his government recognise neither the legitimacy of the TK – due to the unlawful appointment of some judges to it under the rule of the former Law and Justice (PiS) government – nor of Święczkowski, a close ally of former PiS justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro.

That was followed this week by the current justice minister, Adam Bodnar, suspending the deputy prosecutor general, Michał Ostrowski, who is investigating Święczkowski’s accusation. Bodnar’s office referred to an “obvious and gross violation of the law” in Ostrowski’s handling of the case, while senior PiS figures accused Tusk and the justice minister of interfering to prevent an investigation into their own alleged crimes.

The justice minister has suspended a prosecutor investigating claims by the head of the constitutional court that the government is guilty of a "coup d'état".

The opposition says the government wants to block an investigation into its own alleged crimes https://t.co/Ec00H4a44u

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 11, 2025

Those developments are just the latest chapter in an all too familiar story, in which Tusk’s administration, which replaced PiS in power in December 2023, refuses to recognise its predecessor’s judicial reforms, while institutions that remain controlled by PiS-era appointees accuse the new government of itself violating the law. It has created a deadlock that seems impossible to resolve.

But this is not the first time that Poland has faced such a political crisis. In the 1980s, the communist authorities clashed with the Solidarity trade union and opposition group amid growing economic problems, social unrest and protests against the government.

They were able to resolve that crisis in 1989 by holding the Round Table talks, a series of discussions between representatives from both sides whose aim was to negotiate political, economic and social reforms that would help the country transition towards a more stable future.

The subsequent Round Table agreement led to partially free elections and, as a result, the collapse of communism in Poland.

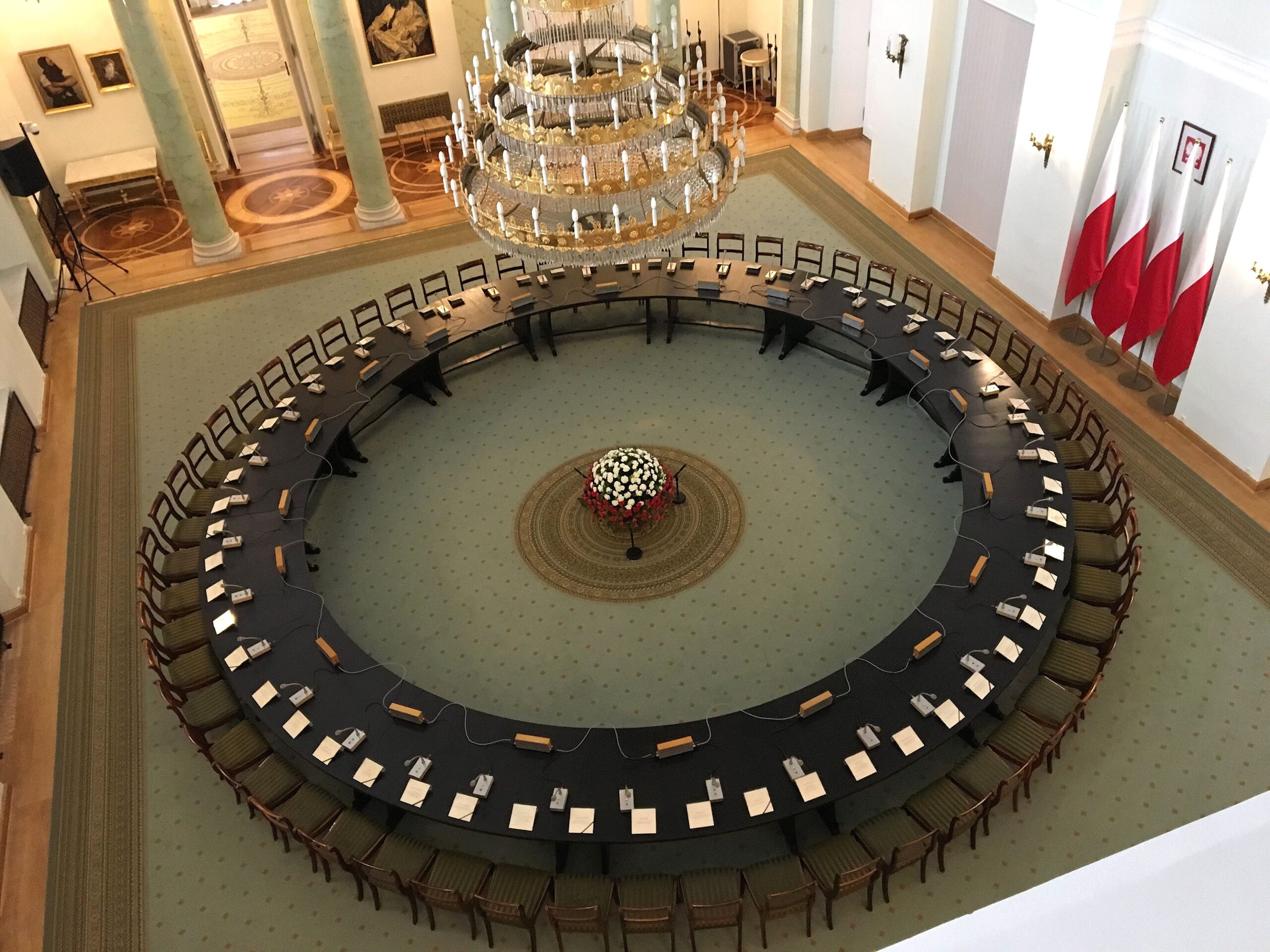

The round table used during the talks in 1989 (image credit: Dawid Drabik/Wikimedia Commons, under CC BY-SA 3.0 PL)

How we got here

As historian and political scientist Antoni Dudek has argued, today’s rule-of-law dispute has its roots in decisions made about judicial independence during the Round Table talks. But it is that format which may hold the key to unlocking the present rule-of-law standstill in Poland.

Following the talks, Solidarity had wanted to ensure that the judiciary would be completely independent since, according to the Round Table agreement, the communists were to control both the legislative and executive branches of government.

But the issue of the judiciary soon became secondary when Solidarity unexpectedly won a landslide victory in the elections, thereby making redundant the assumptions of the agreement and enabling them to later take control of both the executive and the legislature.

At the time, respected pro-Solidarity judges such as Adam Strzembosz argued against purges from the courts and for maximum independence of the judiciary. That came at the price of judges who had presided over political persecution against Solidarity continuing on the bench.

It is notable how little progress was made in cases brought against former communist officials for their actions in 1981 during the unconstitutional and violent enforcement of martial law. The failure to hold such figures to account and the continued presence of “post-communist” judges has been a particular bone of contention for PiS and its supporters and was part of its reason for undertaking judicial reforms during its time in power.

On this day in 1981, Poland's communist authorities introduced martial law, deploying tanks and soldiers onto the streets in response to growing opposition to the regime.

Dozens were killed and thousands were arrested before it was lifted in 1983 https://t.co/x7Zlor045O

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 13, 2022

By the early 21st century, concerns had also emerged about the high level of judicial autonomy, with judges enjoying blanket immunity in Poland and themselves electing members of the National Judicial Council (KRS), the body that oversees the appointment and supervision of Polish judges.

Questions were raised not only by conservatives – with PiS regularly condemning this self-regulating “judicial caste” – but also by liberal lawyers such as Andrzej Rzepliński, a former Constitutional Tribunal (TK) chief justice, who has argued for the KRS to be elected by a broader group than just senior judges.

The present rule-of-law crisis was triggered by a battle over the TK, which began in 2015 after PO’s candidate, the incumbent Bronisław Komorowski, lost the presidential election to the PiS-backed Andrzej Duda. PO was also predicted to lose the parliamentary elections later that year, which would mean PiS would control both the executive and the legislature.

Faced with that prospect, PO attempted to appoint five new judges to the TK. Three of those were to replace judges whose terms would expire after the elections but before the new government took office in November. The remaining two would replace judges whose terms expired in December.

PiS read that as PO attempting to pack the TK with its appointees so that it could control the judiciary. After winning the October parliamentary elections and taking office, PiS responded by invalidating both the appointment of the two disputed judges and the three who had been legitimately chosen. PiS then appointed five of its own judges.

The @EU_Commission has launched further legal action against Poland.

It says that two rulings by Poland's constitutional court – which found parts of EU law to be inconsistent with the Polish constitution – "violated and challenged the primacy of EU law" https://t.co/DShAPKOBla

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 15, 2023

PiS then proceeded to take over the KRS by having most of its members elected by parliament, a move that kept to the letter of the constitution, which does not specify the method of election, but was clearly in contradiction of the principle of judicial independence. A number of Polish and European court rulings have found that PiS’s reforms have rendered the current KRS illegitimate.

Since 2017, the KRS has nominated hundreds of judges for appointment by the president, who holds the constitutional power to do so. Those appointments are considered illegitimate by the ruling coalition, with the individuals in question being referred to as “neo-judges” and Bodnar restricting their right to adjudicate in cases.

That has in turn put into doubt thousands of court judgments issued in the last few years. For example, in January an appeals court in northwestern Poland overturned a life sentence against a man convicted of murdering three women on the grounds that a “neo-judge” had adjudicated the case. The accused will have to be retried, causing grief to the victims’ families and costing taxpayers.

The Tusk government also does not recognise the legitimacy of the TK – due to the abovementioned illegitimately appointed judges – and also parts of the Supreme Court, which contains many “neo-judges”, including its chief justice.

Yet that position can appear selective: the ruling camp has refused to recognise a decision by a Supreme Court chamber created by PiS and staffed entirely by “neo-judges” to restore public funding stripped from PiS; but it did recognise a ruling by the same chamber to confirm the results of the election that brought Tusk’s coalition to power.

The crisis surrounding the finances of Poland’s opposition PiS party took a further twist today after the electoral commission refused to accept a recent ruling to restore PiS’s public funding issued by a Supreme Court chamber whose legitimacy is disputed https://t.co/glmiYGAwoh

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 16, 2024

That selectivity means that a potential crisis is looming over the coming presidential election.

The government has chosen to defy the abovementioned court order because it believes PiS violated election expenditure rules. In challenging the chamber’s decision, the Tusk administration has, according to the chair of the National Electoral Commission, Sylwester Marciniak, put into question the status of the election since it is rejecting the legitimacy of the court legally empowered to certify its results.

No easy solutions

Supporters of the government claim that this mess is entirely of PiS’s making and argue that Tusk has not been able to yet resolve it because PiS-aligned President Andrzej Duda remains in office with the power to veto their legislation.

They claim that, if May’s presidential election is won by a coalition-aligned candidate, the rule-of-law crisis would be easily resolved, as the government’s reform efforts would no longer be obstructed by a presidential veto.

But things may not be that simple. First of all, it remains to be seen whether a government-aligned candidate will indeed win the presidency. Rafał Trzaskowski of Tusk’s Civic Coalition (KO) is favourite but by no means a certainty. If PiS-backed candidate Karol Nawrocki wins, Tusk’s coalition will again find its agenda stymied.

Moreover, even if Trzaskowski wins, and the government is able to move forward with reforms of the TK, Supreme Court and KRS, many PiS-era judges will remain in place. In particular, the TK will continue to have a majority of PiS-nominated judges who were appointed legally.

As the Council of Europe’s rule-of-law advisory body, the Venice Commission, recently pointed out, only three of the TK’s 15 judges were elected illegitimately and there is no provision in the constitution for legally removing the others, all of whom were appointed under PiS.

Given that the ruling coalition’s parliamentary majority is well short of the two thirds required to change the constitution, they cannot radically overhaul the TK without the opposition’s consent.

And there are also potential storm clouds on the more distant horizon.

PiS still maintains strong electoral support. It won the largest share of the vote in last year’s local elections and only marginally came second to KO in the European elections. The party will still be a political force to be reckoned with in the 2027 parliamentary elections, especially given polls indicating the growing unpopularity of Tusk’s administration.

More Poles (35%) think that the rule of law has got worse under Tusk's government than believe it has improved (24%).

A further 28% think there has been no change, finds a new poll https://t.co/KkiuY2vDSW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 5, 2025

That opens up the possibility of a future PiS-led government with a parliamentary majority seeking to reverse any of Tusk’s reforms and targeting his officials in the same way the current government has targeted PiS politicians.

PiS has already said that, if it returns to government, it will seek to put on trial any officials in the current ruling coalition who have violated the laws on public media, funding of political parties and replacing the national prosecutor, have unconstitutionally dismissed ambassadors, or have bypassed legislation with parliamentary resolutions.

Time for another Round Table?

Since serious judicial reform requires constitutional change and political consensus of the sort not seen since the Round Table talks, it may be time for that very table to be dusted down and used in deliberations between the government, the opposition and representatives of the judiciary.

To get a deal, all sides would have to compromise. The Tusk administration would have to accept the recommendation of the Venice Commission, which warned that it should not tar all the “neo-judges” with the same brush and must design a system that makes decisions on their future on a case-by-case basis.

A Polish court has for the first time removed from adjudication judges appointed through a state body rendered illegitimate by reforms introduced under the former PiS government https://t.co/9u3rx4NqrB

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 8, 2024

PiS would need to accept that a new KRS will be elected mainly by judges and that the three illegally elected TK judges must leave the court. However, KO would have to accept that the remaining TK judges were legitimately elected.

In order to deal with other concerns, both sides could agree to constrain the immunity of judges from prosecution and consider the introduction of jury trials to increase public participation in the judicial process. In addition, lesser cases could be handled by a newly constituted corps of justices of the peace to help speed up judicial proceedings.

Given that the current polarisation between KO and PiS has served well the electoral fortunes of both parties, it is difficult to imagine the two adversaries sitting down together and thrashing out a new deal on the future of the judiciary. Yet the international situation, in particular the Donald Trump presidency, may make that a necessity.

Trump is on friendlier terms with PiS politicians than he is with their counterparts in the ruling coalition. If the Tusk government chooses, as is likely, to simply see victory in the presidential election as a green light for making judicial reforms without seeking consensus for them, it may clash with the White House.

Poland's opposition PiS party chanted Donald Trump's name in parliament after news of his victory.

Ahead of the election, the head of the PiS caucus called on PM @donaldtusk – who recently said Trump has a "pro-Russian attitude" – to resign if Trump won https://t.co/wpgpm48q91

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) November 6, 2024

The Trump administration cannot sanction Poland by denying it funding – as the European Commission did when the country was governed by PiS – but it can pull levers connected with defence policy, trade and investment, and Poland’s international standing.

The Round Table agreement became possible because old foes recognised the world was changing and that they could not eliminate each other without the danger of Poland descending into chaos or worse.

The situation is similar today, even if Poland is a much stronger country than it was back then. Neither side can eliminate the other – or they would have already done so – and the international situation, as well as Poland’s long-term development and stability, makes reaching consensus a more desirable option than continuing to confront one another.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Trybunał Konstytucyjny (under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 PL)