Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

By Aleks Szczerbiak

Most Poles feel that the governing coalition has failed to deliver key reforms and lacks a policy agenda beyond holding its predecessor to account for alleged abuses of power.

This could be a problem for the liberal-centrist ruling party’s candidate in the crucial summer presidential election if it turns into a plebiscite on the incumbent government.

More opponents than supporters

In December 2023, a new coalition government led by Donald Tusk, who was Polish prime minister between 2007-14 and then European Council President from 2014-19, was sworn in, ending the eight-year rule of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) party. Tusk is leader of the liberal-centrist Civic Platform (PO) which once again became the country’s main governing party.

The new coalition also includes the eclectic Third Way (Trzecia Droga) alliance – which itself comprises the agrarian-centrist Polish People’s Party (PSL), and the liberal-centrist Poland 2050 (Polska 2050) grouping formed to capitalise on TV personality-turned-politician Szymon Hołownia’s strong third place in the 2020 presidential election – and the smaller New Left (Nowa Lewica) party, the main component of a broader Left (Lewica) electoral alliance.

Last month marked the first anniversary of the Tusk government taking office and opinion surveys indicate that most Poles are disappointed with its performance.

Polls conducted to mark one year since @donaldtusk took power show that most Poles negatively assess the work of his government so far and many more feel their lives have got worse than better.

Women and young people are particularly disappointed https://t.co/QWZWvbyQbW

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 13, 2024

For example, a United Surveys poll for the RMF broadcaster and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna daily found that 51% of respondents evaluated the Tusk government negatively (21% very negatively) compared with only 40% who held a positive view (6% very positive).

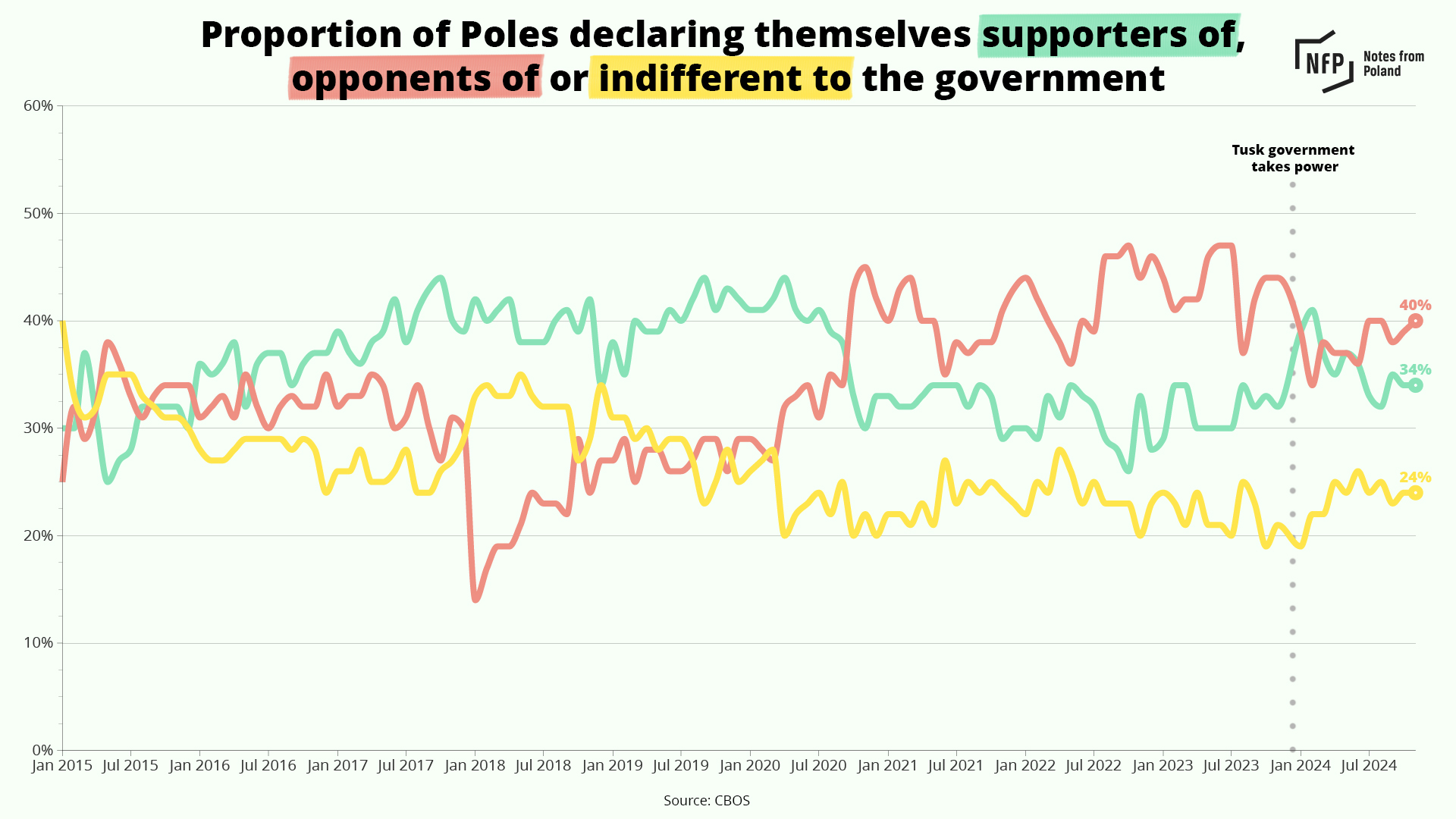

Monthly polling conducted by the CBOS agency also found that the number of Poles describing themselves as government supporters fell from 41% in February 2024 to 32% in December, while the number of opponents increased from 34% to 40% over the same period.

For sure, last year also saw a considerable strengthening of PO. According to the Politico Europe poll aggregator, since January the party has been consistently ahead of PiS in opinion surveys and is currently averaging around 35% support compared with 33% for the right-wing opposition. The June European election was the first time that PO came out top in a national poll since 2014.

However, the party’s boost in support came largely at the expense of its junior governing coalition partners. The biggest loser was undoubtedly Third Way, which had secured 14% in the October 2023 parliamentary election and, according to Politico Europe, stood at 17% at the start of last year but is now only averaging around 10%.

Support for The Left has fallen from 9% at the beginning of 2024 to only 7%. The overall balance is that the governing parties would struggle to retain a parliamentary majority if an election were held today.

Failing to deliver key reforms

So why has support for the Tusk government slumped? Firstly, there is a widespread feeling that it has failed to deliver on the majority of its election pledges.

PO promised to implement 100 reforms in its first 100 days in office, but the Demagog website estimates that only 15 of these have been fully, and a further 27 partially, realised.

For example, it has postponed radically increasing the annual tax-free income tax allowance to 60,000 złoties, one of its flagship election pledges.

Some liberal-left voters are particularly frustrated that the government has failed to pass even modest reforms to fulfil its high-profile election promises on moral-cultural issues.

Speedy liberalisation of Poland’s restrictive abortion law was seen as a key factor motivating record turnout among younger voters in the 2023 election.

Other factors explaining the government’s falling popularity are economic challenges, particularly the fact that in recent months the level of inflation has increased to among the highest in Europe, especially after the government partially ended a freeze on energy prices.

Poland's government came to power exactly one year ago on a pledge to end the country's near-total abortion ban.

But that promise remains unfilled, leaving many women angry and disillusioned, write @AlicjaPtak4 and @Chrisatepaauwe https://t.co/q9w8NqP4mI

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 13, 2024

The government’s supporters argue that PiS left behind a very problematic economic and political legacy, together with numerous legal and institutional obstacles.

They say that the fact that the government has to “cohabit” with PiS-aligned President Andrzej Duda, and lacks the three-fifths parliamentary majority required to overturn his legislative veto, has acted as a major block to its efforts to implement deep institutional reforms.

In addition to vetoing or threatening to veto key legislation, Duda can also delay the implementation of laws by referring them to the Constitutional Tribunal for review.

This is a powerful body that rules on the constitutionality of Polish laws, all of whose members were appointed by the previous PiS-dominated parliaments, but whose legitimacy the current ruling coalition does not recognise.

Government backers argue that the ideologically diverse nature of the governing coalition also explains why it has not been able to deliver on many of its election promises.

Is Duda really such an obstacle?

PiS, of course, vehemently denies that it left the country in ruins, and even many of those who believe this can tire very quickly of a government that seeks to blame all of its misfortunes on its predecessor.

For sure, Duda made it clear that he would block government attempts to liberalise the abortion law and unpick its predecessor’s key justice system reforms if he felt they undermined the legitimacy of his judicial appointments made since PiS introduced its changes.

However, the government’s critics point out that Duda has only actually vetoed four draft laws while making four further referrals to the Constitutional Tribunal for so-called “preventive control” (where the legislation does not come into force until the tribunal has reviewed it) while allowing over 100 others to pass unhindered.

Moreover, the president has not given any indication that he questions the government’s core socioeconomic priorities; indeed, some of these, increasing welfare payments for example, are actually a continuation of its predecessor’s policies.

President Duda has refused to sign two bills passed by the governing coalition that would overhaul and depoliticise the Constitutional Tribunal (TK).

Instead, he has sent them to the TK itself for assessment, saying he believes them to be unconstitutional https://t.co/6AuQsUdzYt

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 8, 2024

For sure, in some cases, Duda has hindered the government’s attempts to replace PiS’s state office nominees where this requires legislation or presidential sign-off, such as ambassadorial appointments.

However, the Tusk administration has used various legal get-arounds and loopholes to, for example, replace the management of the state-owned media and the national prosecutor appointed by its predecessor.

Moreover, in these instances, and other areas where Duda’s critics say that the president is blocking what they see as “restoring the rule of law”, PiS argues that the presidential veto (or potential veto) is protecting institutions that they claim the government is trying to dismantle, or take control of, unconstitutionally.

Poland has risen in @TheWJP's annual Rule of Law Index, partially reversing the decline seen under the former PiS government https://t.co/t5SahvkAyk

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 24, 2024

Interestingly, some government supporters have used a “transitional justice” logic to justify some of its more legally questionable moves, such as its refusal to recognise judicial bodies that they say are improperly constituted, on the grounds that constitutional safeguards can (indeed, should) sometimes be ignored when taking steps to restore legal order to institutions that have been corrupted or whose legitimacy is questionable.

However, the government’s critics argue that, even if one accepts this analysis of the nature of PiS’s systemic reforms and elite appointment policies (which it strongly contests, of course), this kind of “state of emergency” framing uses the same justificatory logic that the previous ruling party used: that its reforms were necessary to repair the post-communist networks and flawed institutions and elites that emerged following Poland’s distorted post-1989 transition to democracy.

An excuse for inaction?

The current government is certainly an ideologically heterogeneous one and this has undoubtedly played a role in the failure to pass some legislation on moral-cultural issues.

For example, PSL, the most conservative element of ruling coalition, joined the conservative opposition in voting down a draft law to decriminalise assistance with abortions and has blocked the adoption of legislation introducing same-sex civil partnerships.

Poland’s government has presented a bill to introduce legally recognised partnerships for same-sex couples https://t.co/PStNb7DoFz

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 19, 2024

However, with some exceptions (such as reducing employers’ national insurance contributions and housing policy) the coalition has not encountered huge problems in agreeing governing priorities, particularly on socioeconomic issues. Indeed, even some government supporters who accept many of the difficulties that it faces, still feel that these are being used as an excuse for inaction.

Tusk is extremely skilled at making headline-grabbing announcements that dominate the news agenda, but he has always been sceptical of grand political projects and visions. As a consequence, the prime minister has failed to provide his government with any sense of a long-term strategy and overarching set of programmatic goals.

Critics say that the Tusk government could at least have challenged Duda by provoking vetoes on a number of issues, such as abortion, which could then provide a rallying point for anti-PiS voters to turn out and vote in this summer’s crucial presidential election.

With President Duda leaving office next year, the election to choose his successor will be pivotal in determining to what extent the government can implement its agenda.@AleksSzczerbiak explains what is at stake and which candidates may be standing https://t.co/fesUQfOThb

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 16, 2024

The outcome of this election will have huge implications for whether the ruling coalition can govern effectively during the remainder of its term of office, which is set to run until autumn 2027.

The current front-runners are: PO deputy leader and Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski, who lost narrowly to Duda in 2020, and PiS-backed head of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) Karol Nawrocki.

Trzaskowski’s victory would remove a major obstacle to the Tusk administration’s institutional reform and elite replacement project and allow it to finally undo the remainder of its predecessor’s legacy.

If Nawrocki wins, the government can expect continued resistance from the presidential palace for the remainder of its term and it could even pave the way for an early parliamentary election.

Do Poles still want a “reckoning”?

In fact, there is a growing perception that the government’s main raison d’être is a so-called “reckoning” (in Polish: rozliczenie) with its predecessor’s alleged abuses of power. This involves a combination of elite replacement and utilising various state instruments to hold the previous government to account.

It is, of course, much easier to secure agreement over elite replacement than policy matters within a programmatically diverse coalition; indeed, sharing out the spoils of office is often the “glue” that holds together Polish governments and political formations.

Other key instruments to achieve this “reckoning” include high-profile special parliamentary commissions and a raft of criminal investigations into allegations of misuse of state resources by figures associated with the previous administration.

Hungary has granted asylum to a Polish opposition politician wanted for alleged crimes committed as a minister in the former government

It says he would not receive a fair trial. But Poland's foreign minister says they view the decision as a “hostile act” https://t.co/CNOSA3CS6S

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 19, 2024

PiS supporters portray these actions as a political witch hunt, but the government’s most radical supporters actually want even more decisive action, especially as the Tusk administration has frequently referred to its predecessors as “thieves” and an “organised criminal group”.

However, other voters appear to be losing interest in the “reckoning”, and there is even a growing feeling among many of the government’s supporters who agree with the policy that the Tusk administration also needs a more positive and forward-looking policy agenda.

A referendum on the incumbent or its predecessor?

Evaluations of the Tusk government matter because they could have a significant impact on the outcome of the presidential election.

Polls suggest that Trzaskowski is the clear favourite and the governing parties will be hoping that they can rekindle the huge electoral mobilisation that led to a decisive rejection of PiS in 2023. PiS, on the other hand, will try and use the presidential poll to channel growing discontent with the Tusk administration.

A majority of Poles, 53%, say life has got harder in 2024 under Tusk's government than it was in 2023 under the former PiS government. Only 33% say it has got easier.

Even among the ruling coalition's voters, 29% say things are worse, finds the poll https://t.co/RQV5DQoPPq

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 29, 2024

If this creeping disappointment becomes more decisive then this could be problematic for Trzaskowski. The Polish political scene is deeply polarised with little evidence of any significant voter transfers between the two large blocs, so electoral competition revolves primarily around the extent to which each side can mobilise and demobilise their supporters and opponents.

Although disillusioned government supporters are unlikely to vote for Nawrocki, some of them may decide to simply sit the presidential election out. In other words, PiS is hoping that the presidential election will be a referendum on the current government, while PO wants it to be (another) plebiscite on its predecessor.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Kancelaria Premiera/Flickr (under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)