By Katarzyna Skiba

The president’s decision to veto a bill recognising Silesian as a regional language has reignited a debate that is ostensibly linguistic – over whether Silesian is a language or a dialect – but at its heart is a struggle over culture, identity and, for some, the integrity of the Polish state itself.

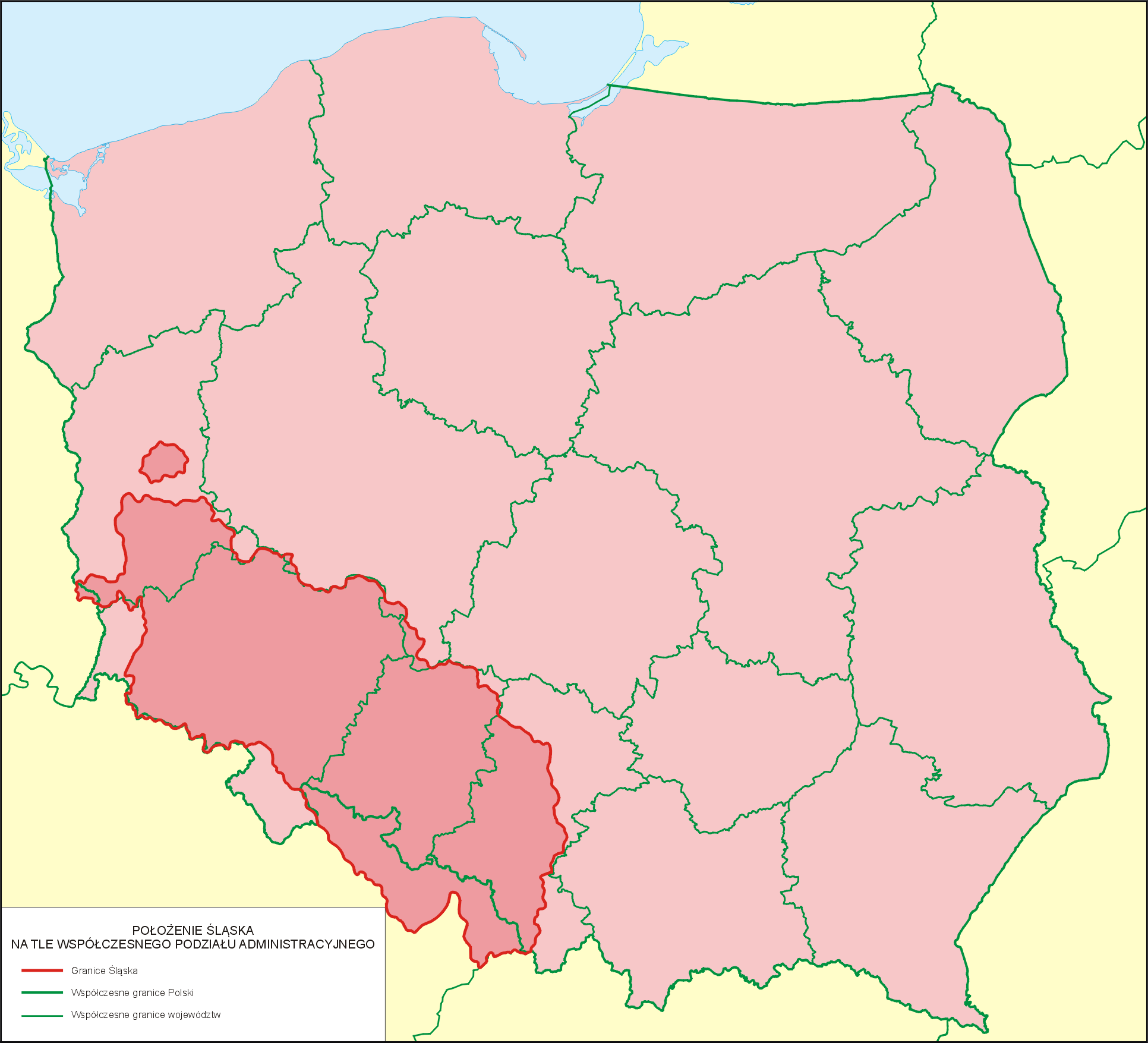

The historical region of Silesia stretches across the southwest of Poland, extending into the eastern edges of the Czech Republic.

Owing to its plentiful sources of coal and iron ore, control of the area has often been contested by regional powers. Over a period of 600 years, it was ruled variously by Bohemia, Austria, Prussia, Germany and Poland.

Today the region, which has been part of Poland since the end of the Second World War, is the subject of a different kind of conflict – one over linguistic and cultural identity.

A map of Poland, with the region of Silesia highlighted in the southwest. Image credit: Poznaniak/Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0

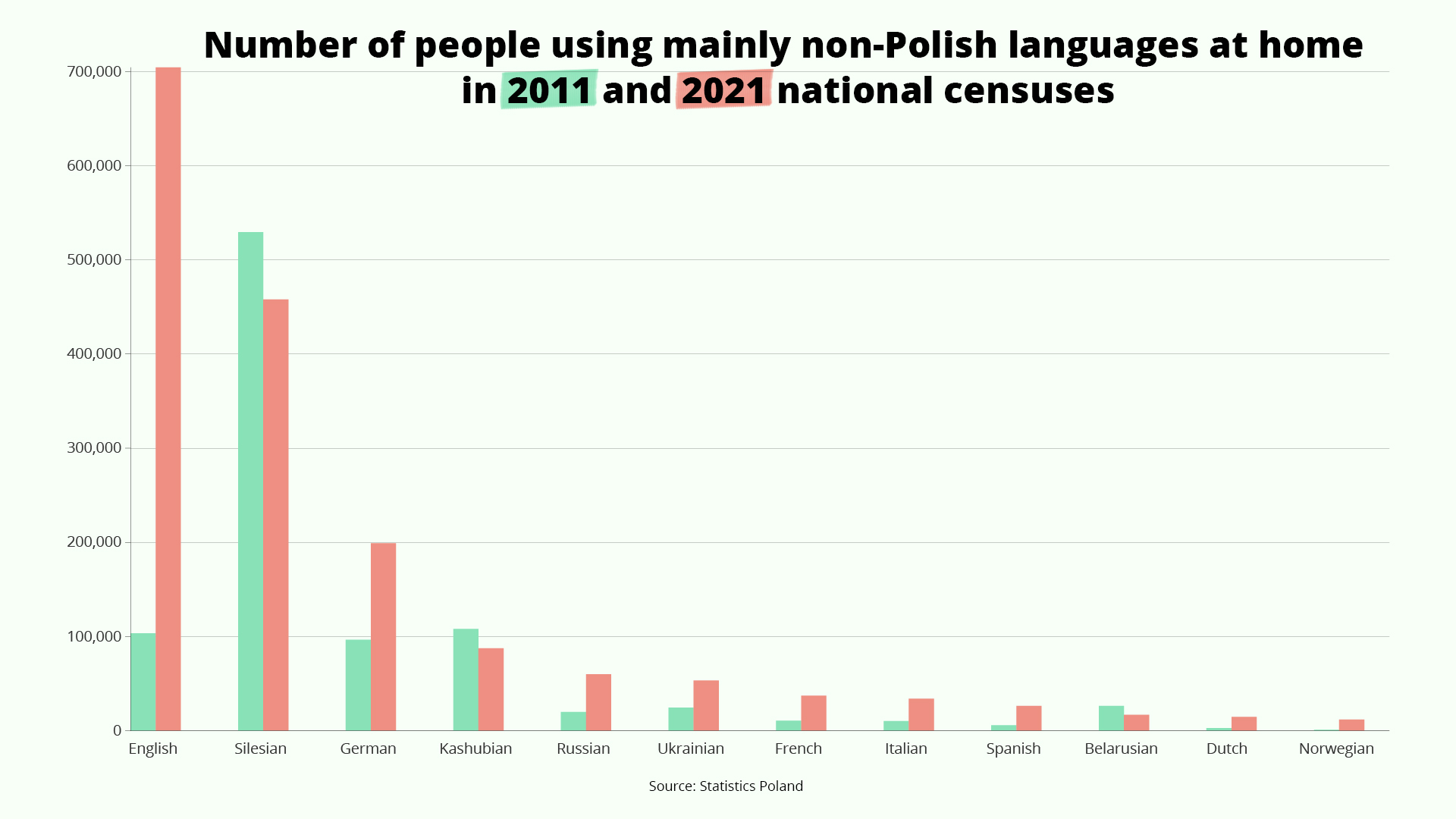

According to the latest census data from 2021, around 460,000 Poles use Silesian as their primary language at home. Yet it does not have the status of a regional language and is instead often referred to as a dialect or “ethnolect”, meaning a variety of language associated with a certain ethnic group.

Adding Silesian to Poland’s current sole recognised regional language, Kashubian, was one of the 100 policies that Donald Tusk’s Civic Coalition (KO) pledged to implement in its first 100 days in office if it came to power at October’s parliamentary elections – which it did.

However, after a bill to that effect was approved by the government’s majority in parliament, President Andrzej Duda, an ally of the former national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) government, vetoed it.

Tellingly, the president cited not only linguistic concerns – arguing that most linguists regard Silesian as a dialect of Polish rather than its own language – but also “the current social and geopolitical situation”.

President Duda has vetoed a law that would have made Silesian a recognised regional language in Poland.

He argued that Silesian is a dialect of Polish, rather than a language in itself, and also cited national security concerns https://t.co/QpFfVXnaes

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 29, 2024

This hinted at an argument more directly expressed by other figures from the right-wing opposition, who argue that encouraging stronger regional identities threatens Polishness and the integrity of the Polish state. Some even suggest the movement to recognise Silesian is part of a foreign plot to break up Poland.

“The German plan to break up the Polish national community has been stopped today,” tweeted Janusz Kowalski, a former deputy minister in the PiS government and now an opposition MP, in celebration of Duda’s veto.

A contested tongue

But for many Silesians, Duda’s decision was an affront to their linguistic and cultural heritage.

“I have a great deal of regret about the president’s justification,” said Łukasz Kohut, an MEP representing Upper Silesia’s capital city Katowice, in an interview with state broadcaster TVP Info following the veto.

“According to the president, Silesian culture and the Silesian language are dangerous to Poland. I would like to say that this is not at all against Poland, it is enriching Poland. Poland is multicultural.”

“I know that the president is persona non grata in many Silesian homes after this decision,” he added.

Listen to this! Łukasz Kohut switches from Polish to Silesian midway through a speech in the European Parliament. https://t.co/G2IhwNnWUq

— Jørn Holm-Hansen (@JornHolmHansen) March 10, 2023

Linguists have long debated whether Silesian is a language, a dialect or an ethnolect. But its formal codification and growing literary usage have shifted many towards regarding it as a language.

Moreover, Silesian has several varieties of its own. These include Cieszyn Silesian, a dialect spoken by tens of thousands of people living on both sides of the Polish-Czech border, and the Niemodlin, Prudnik and Sulkovian dialects, spoken by a minority of inhabitants of towns and villages in Upper Silesia.

“In my opinion, the development of Silesian over the last two decades has clearly moved [it] from the definitional framework of a dialect to that of a language,” says sociolinguist Henryk Jaroszewicz.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. The article continues below.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

According to Dorota Rembiszewska, a linguist and dialectologist at the Polish Academy of Sciences, this shift is best illustrated by comparing Silesian with other Polish dialects.

“If we compare it with, say, the subdialects or dialect of Lesser Poland, we see how it is developing in a completely different direction. Silesian has a rich literature and there is, indeed, an orthography textbook.”

However, prominent linguist Jan Miodek has long argued that Silesian is a dialect of Polish and should continue to be recognised as such.

“[Silesian] is very characteristic and expressive,” said Miodek in an interview with the state broadcaster’s TVP Polonia channel following Duda’s decision. “It could be said that of all the Polish dialects, it is the one most often heard on the streets of large cities.”

Silesian, which is spoken in southwest Poland, has been added as a language on Google Translate.

The decision comes shortly after Poland’s own president vetoed a law recognising Silesian as a language. He says it is actually a dialect of Polish https://t.co/mXhmFgbchU

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 30, 2024

Still, he argued that “there is not a single structural feature that would distinguish the Silesian dialect from the Greater Poland dialect or the Lesser Poland dialect”, referring to two other historical regions.

“Language is created by its speakers, language is the carrier of culture,” said Katarzyna Kłosińska, the chair of the Polish Language Council (RJP), in a Senate committee meeting in May. “If we talk about Silesian culture and identity, we should assume that the language is an expression of this identity.”

Yet the RJP, which regulates the Polish language, does not officially support recognition of Silesian.

Jaroszewicz also highlights how legal recognition would not mark the end of the debate.

“The Kashubian language has, according to Polish law, been a regional language for almost 20 years,” he says, “but even today there are works published by dialectologists who do not respect this state of affairs” and treat Kashubian as a dialect.

Nevertheless, legal recognition by the state would bring many benefits, allowing the languages to be taught in schools and used in local administration in municipalities where at least 20% of the population declared that they speak it in the last census.

“There are a huge number of people who use Silesian and want the speech they use to be called with appropriate respect, to have appropriate prestige,” says Polish linguist Jolanta Tambor.

Advocates believe that legal recognition would also raise the status of Silesian in the national consciousness and help to combat longstanding stigmas and stereotypes surrounding the region.

“It would no longer be some dialect of funny people who are covered in coal, eat karminadles [traditional Silesian meatballs] and support [football club] Górnik Zabrze,” says Jaroszewicz. “It would just be a normal language.”

A game show has faced complaints from one of Poland’s ethnic groups, the Kashubs, for describing their language as a dialect

They have demanded that state broadcaster TVP issue a correction informing viewers that Kashubian is a legally recognised language https://t.co/37i9V5UrB1

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 28, 2020

But some opponents argue that recognition of Silesian would undermine the status of Kashubian.

“From the point of view of us Kashubians, to inscribe a non-existent Silesian language just because someone got politically attached to it would be depreciating the Kashubian language in the law,” PiS politician and former deputy culture minister Jarosław Sellin told broadcaster Radio Maryja last month.

Such critics also note that Kashubian has a centuries-long written history, including translations of biblical texts dating back to the 16th century. Jaroszewicz, however, points out that the earliest dated literary texts written in Silesian were published in the 18th century.

Fears of Silesian autonomy

Whereas the linguistic dispute tends to focus on scholarly definitions of what constitutes a language, the political debate includes allegations of “separatism”, “pro-German tendencies” and “attempts to break up the Polish state”, notes Jaroszewicz.

In the statement explaining Duda’s veto, his chancellery wrote that “the inevitable hybrid actions that may be taken against the Republic of Poland, related to the ongoing war beyond the eastern border, require that special care be taken for the preservation of national identity”.

“Preservation of national identity is served in particular by the cultivation of the mother tongue,” it added.

Poland’s top annual literary prize has been awarded to Zbigniew Rokita for his book of reportage on the Upper Silesia region.

This year's ceremony was marked by protests from audience members and jurors against the government's border policies https://t.co/y5I7Qj7i7v

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 4, 2021

The president’s office did not specify how recognition of Silesian could impact Poland’s national identity or security. However, political and legal experts suggest that any such threat would be minimal.

“It seems to me that this threat is not realistic, even on the basis of some Silesian identity that can be strengthened through language recognition,” says Przemysław Witkowski, a political scientist who specialises in extremist movements, as well as issues surrounding ethnic and religious minorities in Poland.

He adds that while some fears may come from the examples of independence movements in Scotland and Catalonia, “the unrest among PiS is also related to the very anti-German attitude of this party”, for whom Silesian identity is perceived as “semi-German, quasi-German…also supported by the Germans”, owing to the rule of Prussia over large parts of Silesia between the 18th and 20th centuries.

Although a modern movement for Silesian autonomy, known as Ruch Autonomii Śląska (RAŚ), has existed in the region since 1990, Swen Marondel, a lawyer and co-author of “Inventing a Nation”, an academic article about the ethnic revival in Upper Silesia, notes that “this move towards autonomy has not turned into any real project”, and is present to “an increasingly lesser extent”.

“It is more about efforts to recognise them [Silesians] for a certain cultural distinctiveness rather than to separate the entire region,” he says, adding that Silesians are also a minority within Upper Silesia itself, decreasing the chances that any such movement could inspire a broader fight for autonomy or special status.

This is echoed by MEP Kohut, who claims that “the topic of autonomy was abandoned a long time ago when local government was introduced in Poland”.

Signs in Polish and Silesian have been installed in two Kaufland supermarkets in Silesia.

According to the author of the translations, this proves that Silesian – classified as an ethnolect, not a language – is a living communication toolhttps://t.co/8L4ubjeGUO

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) December 28, 2022

“Even at the apogee of their political successes, movements appealing to the ideas of Silesian distinctiveness or autonomy managed to obtain only single seats in the parliament and provincial assemblies,” says Tomasz Pietrzykowski, a law professor and co-author of “Inventing a Nation”.

“The phenomenon of the Silesian Renaissance is worth seeing primarily in socio-cultural terms,” he adds. “It is rather a chance for modernising and opening up the archaic vision of Poland as a homogeneous state where internal differences are not allowed.”

As the debate around the Silesian language continues, advocates for recognition will be looking towards next year’s presidential elections, in which Duda will not be standing. They hope his successor will be more willing to accept official recognition of Silesian.

“The paradox is that the president’s veto helped more than it hurt,” claims Jaroszewicz. “Many people once again became angry and convinced that they had to do their part.”

“We can expect even more activity and even more advocacy,” he adds.

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Anna Lewanska / Agencja Wyborcza.pl