Google has added Silesian, which is spoken in the historical area of Silesia in southwest Poland, to the languages available on its Translate service.

The decision comes shortly after Poland’s own president vetoed a law that would have recognised Silesian as a language. He says it is in fact a dialect of Polish.

Sweet home Silesia czyli niy ma jak na Ślōnsku🟨🟦

🔥Wczoraj wirtualny tłumacz Google włączył język śląski do grona języków, z jakich można automatycznie przetłumaczyć tekst. Śląski w wydaniu Google Translate nie jest idealny, ale JEST Panie Duda – hybrydowy Prezydencie PiS❗️ pic.twitter.com/ifL7Ekgxls

— Łukasz Kohut 🇪🇺 (@LukaszKohut) June 29, 2024

On Thursday this week, Google announced that it was “adding 110 new languages to Translate”, which would begin to appear on the service over the following days.

As well as Silesian, the new additions include Abkhaz, Cantonese, Crimean Tatar, Dinka, Fijian, Jamaican Patois, Luo, Portuguese (Portugal), Sicilian and Tibetan.

By Friday, Silesian was available on Google Translate.

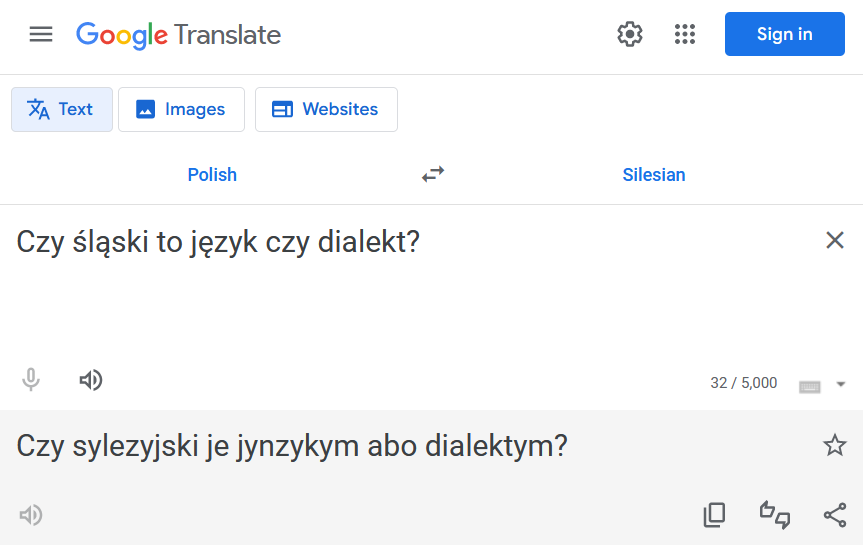

“Is Silesian a language or a dialect?” in Polish and Silesian on Google Translate

Ślonsko Ferajna, a group that promotes autonomy for Silesia, welcomed the addition of Silesia to Google Translate as “a really important milestone for the popularisation of our language”.

However, they added that Google “still needs to be given some time to get it to work properly, because at the moment most of the text generated has significant errors”.

Ślązag, a news website focused on Silesia, also reported that Google’s translations to and from Silesian are often “ridiculous”. It published various examples of such errors.

Tłumacz @Google dodał język śląski do listy tłumaczonych przez siebie ponad 100 języków. Na razie jednak tłumaczenia są bardzo niedokładne. Głównie – śmieszne. #godka #jezykslaski https://t.co/dQ0h6PllgL

— ŚLĄZAG (@Slazagpl) June 28, 2024

Grzegorz Kulik, chairman of the Silesian Language Council and creator of an existing online Silesian translation tool, told Ślązag that he welcomed Google’s decision.

“I’m very happy that the Silesian language is appearing in new technologies because it means that the digital distance between us and large languages is decreasing,” he said.

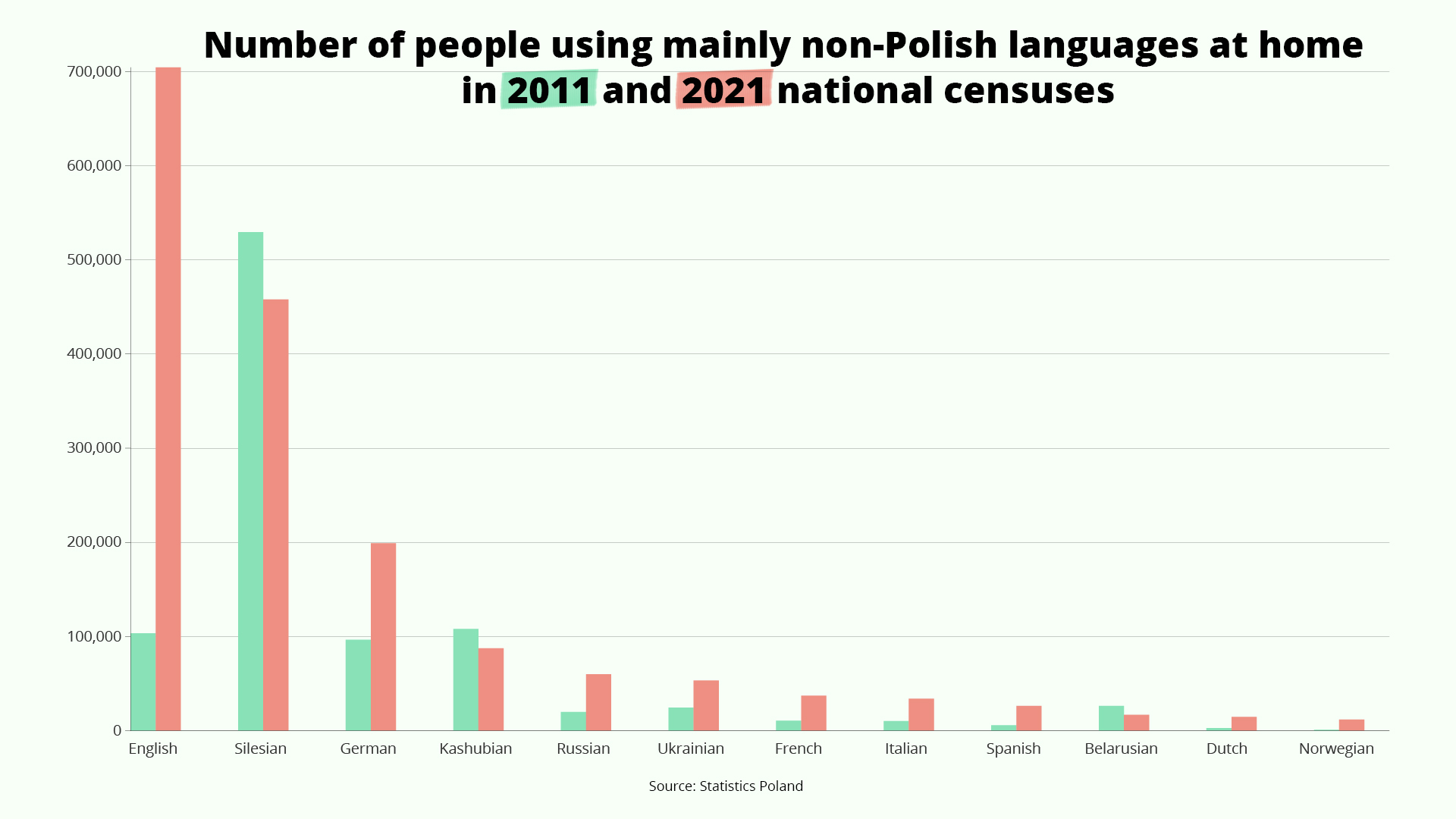

Ślązag noted that Kashubian – which is native to northern Poland and, unlike Silesian, is recognised as a regional language – has not been included in Google Translate. “I regret this,” Mateùsz Titës Meyer, a Kashubian activist, told the website.

In Poland’s 2021 national census, around 460,000 people in Poland said they use Silesian as their main language at home, while 87,600 use Kashubian. Both figures have declined since the last census in 2011.

There has long been a debate about whether Silesian constitutes a separate language or is rather a dialect of Polish. Linguists often describe it as an “ethnolect”, meaning a variety of language associated with a certain ethnic group.

In January this year, Civic Coalition (KO), the group led by Prime Minister Donald Tusk, submitted a bill to parliament that would have recognised Silesian as a regional language.

Such official recognition allows a language to be taught in schools and used in local administration in municipalities where at least 20% of the population declared in the last census that they speak it.

However, although the bill was approved by parliament – where the government has a majority – it was vetoed in May by President Andrzej Duda, an opponent of the government. He argued that linguists regard Silesian as a dialect and also cited national security concerns.

President Duda has vetoed a law that would have made Silesian a recognised regional language in Poland.

He argued that Silesian is a dialect of Polish, rather than a language in itself, and also cited national security concerns https://t.co/QpFfVXnaes

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 29, 2024

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Grzegorz Celejewski / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.