By Agnieszka Wądołowska

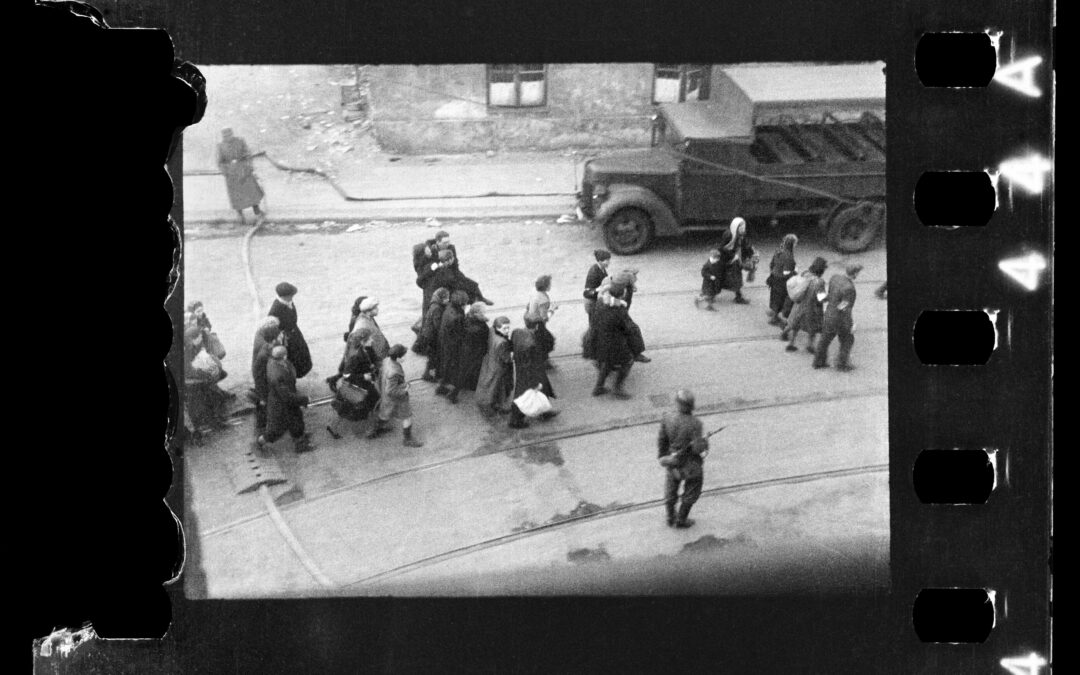

A collection of never-before-seen photographs from the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising has been released, after being discovered in an attic by the family of a Polish firefighter who had smuggled a camera into the ghetto to secretly take them.

The images do not show the fighting itself, which saw hundreds of members of the resistance take part in the largest Jewish uprising during the war.

But they do show the destruction wrought by Nazi-German reprisals – which resulted in tens of thousands of Jews being killed – as well as the deportations that saw tens of thousands more sent to the gas chambers of Treblinka extermination camp.

Photograph: Z. L. Grzywaczewski / from the family archive of M. Grzywaczewski / print from the negative: POLIN Museum

The photographs were taken by Zbigniew Leszek Grzywaczewski, then in his early 20s. His images – some of which have been published before – are the only ones known to have been taken by a non-German source during the uprising.

He had been part of firefighting crews sent into the burning ghetto by the Germans to protect properties that they did not want to be destroyed. During his time there he surreptitiously took photos used a borrowed, camouflaged camera.

“Grzywaczewski is like an underground resistance photo reporter, the sole one going against the German propaganda images,” historian Jacek Leociak, told Notes from Poland.

Leociak explains that the imagery of the ghetto uprising – as presented in both popular culture and in research – is based on photos taken by the Nazis – “by the torturers capturing their dehumanised victims”. Grzywaczewski’s photographs breach that perspective.

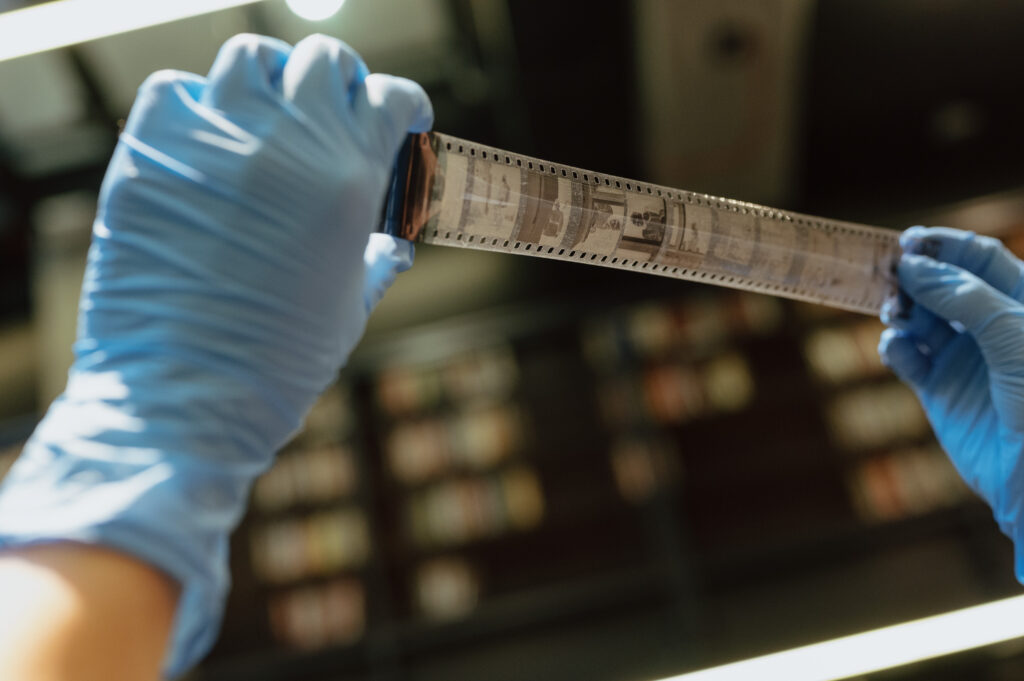

The new images – some of which were yesterday released by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw ahead of an exhibition – are from a 35-mm photographic film discovered by Grzywaczewski’s son, Maciej, in the attic of his sister.

“Our father told us very little about what happened during the war,” says Maciej, who for decades knew nothing about the existence of the photos. No mention of them was found in the diaries kept by his father between the years 1938-1948.

Some of the photos were taken from a window of St Zofia Hospital at the corner of Żelazna and Nowolipie streets in Warsaw, others in courtyards of workshops somewhere in the ghetto, as well as from rooftops and windows.

In order to fit as many images as possible onto the film, at times Grzywaczewski used a tool that allowed for only half of the frame to capture a photo at a given time.

Photograph: Z. L. Grzywaczewski / from the family archive of M. Grzywaczewski / print from the negative: POLIN Museum

Maciej first heard of them when his daughter asked him if he knew that “grandpa’s photos are in Washington”. A friend of hers, doing research about Grzywaczewski, came across them on the website of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

Most likely, in the 1950s Grzywaczewski made prints of the photos and sent them to the US, or brought them to New York himself while serving on a ship, speculates Maciej.

The photos were given to Hillare Laks, a Holocaust survivor and member of a Jewish family that had hidden in Grzywaczewski’s parents’ apartment in Warsaw during the war.

Letters show that Laks had asked Grzywaczewski for the prints, recognising their uniqueness and documentary value. At the back of each print, Grzywaczewski made detailed descriptions.

The description of one of them, presented below, reads: “c.20.4.1943 The setting on fire of houses abandoned by the Jewish population during the evacuation. From the window marked X (balcony) an entire Jewish family, about 5-6 people, jumped onto the pavement and died on the spot. Because they had hidden and did not go out for the evacuation, they could not escape after the house was set on fire, and we could not help them in any way despite the technical possibilities.”

Photograph: Z. L. Grzywaczewski / from the family archive of M. Grzywaczewski / print from the negative: POLIN Museum

The prints passed from Hillare Laks to his daughter, Romana, who donated them to the USHMM when it was created in the 1990s and when Grzywaczewski had already passed away. For some time, Maciej thought that his father could also have handed the original photographic film to the Laks family as well.

However, Maciej realised that the original film may still be in Poland among the possessions his father left when Polish historians preparing an exhibition to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the ghetto uprising this year discovered a letter in which Laks wrote to his daughter mentioning that Grzywaczewski “still has the negatives”.

“I was motivated to look for it by Zuzanna [Schnepf-Kołacz, the curator of the exhibition],” says Maciej. It took days of sieving through boxes.

It was only the very last box that proved to be full of photographic films, one of which contained the images from the ghetto, incongruously alongside private family photographs.

From the family archive of Maciej Grzywaczewski, POLIN Museum

“At first I thought it’s just another series of private photos, as I saw a photo of my mum, but then I caught an image of Jews being led to Umschlagplatz and I knew what it was,” says Maciej.

“I called it the ‘War and Love’ film, as in the film there are first some photos of my mother with her friends in the park, then photos from the ghetto follow, only for the film to finish with some other photos of my mum again.”

Maciej handed over the film to the POLIN museum. Some of the photographs proved to be versions of the images already known, but others have not been seen before. They will all be displayed during an exhibition marking the anniversary of the uprising that will open at POLIN in April.

Photo: Z. L. Grzywaczewski / from the family archive of M. Grzywaczewski / print from the negative: POLIN Museum

Schnepf-Kołacz has appealed to anyone else who might be in possession of photographs or other material relating to the Warsaw Ghetto or the uprising there to contact the museum.

Warsaw’s ghetto was the largest of all those established by Nazi Germany during the Second World War. At one point it held around 460,000 Jews captive in an area of 3.4 square km (1.3 square miles).

The vast majority of those victims died in the gas chambers of Treblinka and Majdanek following deportation. In April 1943, the ghetto uprising temporarily halted those deportations until it was brutally suppressed by the German occupiers.

A visualisation showing the walls of the Warsaw Ghetto superimposed on the modern city.

The full video, produced by @300gospodarka to mark the anniversary of the #WarsawGhettoUprising, can be viewed here: https://t.co/NbriC6TWsl pic.twitter.com/Ye4tYlCLSf

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 19, 2020

Main image credit: Z. L. Grzywaczewski / from the family archive of M. Grzywaczewski / print from the negative: POLIN Museum

Agnieszka Wądołowska is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. She is a member of the European Press Prize’s preparatory committee. She was 2022 Fellow at the Entrepreneurial Journalism Creators Program at City University of New York. In 2024, she graduated from the Advanced Leadership Programme for Top Talents at the Center for Leadership. She has previously contributed to Gazeta Wyborcza, Wysokie Obcasy and Duży Format.