By Weronika Strzyżyńska

In 2006, Magdalena Sperkowska quit her job at a bank and dropped out of university to leave Poland and go to work as a cleaner in the UK. After a few years she found a stable job at a baby bottle factory, where she worked her way up to the manager’s office.

But in 2019, after over a decade of employment, she was made redundant, along with the rest of the factory’s staff. The company was closing its UK operation and relocating to the Netherlands.

“We all think it’s because of Brexit,” Sperkowska says from her new flat in Bydgoszcz, a city in northern Poland, “but the company never confirmed it.”

Brexit the “final push”

In September 2020, Sperkowska, 38, along with her partner Emil Białas, 40, and their eight-year-old son Borys, joined the growing number of Polish migrants who have returned to Poland since the 2016 Brexit referendum.

However, she is careful to stress that Brexit was not the only motivation behind her decision. “We always invested our savings in Poland,” she says, “in the back of our minds we knew that we definitely wanted to come back.”

Magdalena Sperkowska and Emil Białas

The job loss was just a “final push” which persuaded Sperkowska and her partner to sell their property in a village in Suffolk, and pursue their dream of building a home in Poland.

Her story is far from rare. Some 70% of respondents who have returned to Poland since 2015 said that Brexit did not play a role in their decision, says Olga Czeranowska, a researcher at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Warsaw who is currently conducting a study on Polish and Lithuanian returnees from the UK.

Although Poles are the second largest foreign-born population in the UK, with recent figures showing that they have lodged more than a million applications to the EU Settlement Scheme, there is no doubt that many have returned to Poland in the five years since the referendum.

The prime minister last week hailed the fact that many Polish emigrants are returning to Poland, which he said would become "the best place to live in Europe" thanks to the government's economic programme https://t.co/MNGg394fU8

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 17, 2021

Exact figures remain unclear, but according to new population estimates by the British Office for National Statistics the Polish immigrant population in the country was the lowest in seven years in 2020, down to 738,000 from 1.02 million in 2017.

“We found that every person had a conglomerate of reasons for their return,” Czeranowska says. “No one makes such a big choice based on one issue, and it appears to me that Brexit does play a role somewhere in the background.”

“It could cause someone to feel uncertain about their job, or deepen their sense of not being at home or not being fully accepted by society.”

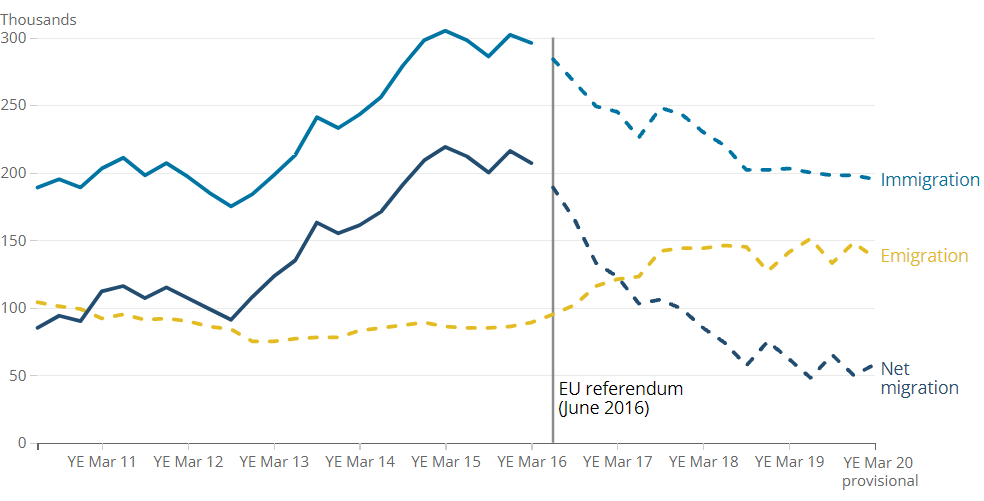

Immigration and emigration to the UK (ONS)

“After the referendum we definitely experienced, perhaps not racism, but definitely xenophobia,” says Zula Rabikowska, a photographer who moved to Poland six months ago after living in the UK since she was 11 years old.

“We had things thrown at our windows. My mum was attacked by teenagers on the bus when they heard her speaking Polish on the phone.” But while Brexit prompted her deeply personal project, Citizens of Nowhere, she is another who does not cite the referendum as the reason for her choice to relocate.

“If anything, Brexit actually kept me in the UK longer,” she says. At the time of the referendum, Rabikowska was preparing to move overseas. However, having travelled extensively throughout her adult life, she realised she had spent too many days outside of the UK to apply for British citizenship.

Consequently, her plans to move had to be put on the backburner. While she was not initially planning to move to Poland, she found herself relocating to Kraków for personal and family reasons.

Zula Rabikowska after returning to Poland (credit: @Zula Rabikowska)

The ongoing wave of re-immigration is also visible in the proliferation of Facebook groups, forums, and blogs dedicated to the topic of returning to Poland from the UK. Białas and Sperkowska themselves each have their own popular YouTube channels, Koszty Budowy and Vlog z Życia, documenting their return to the country.

Sperkowska says that her videos aim to show the “honest truth” about life in Poland. “Many people don’t know if they should return,” she notes. “It is a very hard choice. They often say that things have changed in England. That prices have gone up.”

Family ties

Sperkowska also says that she found family ties to be a strong magnet attracting her to return.

“When you live in England and something happens, you realise you’re just too far away,” she says. Three years ago, her mother died unexpectedly. “When I found out I was shocked, I didn’t know how to react, I couldn’t even book my ticket,” she recalls. “Of course, I could fly over but there were no same-day flights, I had to wait till later and so on.”

Now, although she is again close to her family, she feels that she missed out on spending time with her mother. “I still struggle, because even though I came back and my dad is here, which is great, I miss Mum a lot,” she says.

“As to why people chose to return, we found that emotional and family reasons, such as being close to family, taking care of a family member, or wanting children to grow up in Poland, came to the forefront,” says Czeranowska.

For Sperkowska and her partner, their son was also an important motivating factor. “Borys did not know his cousins and aunts,” she says, recalling that at family gatherings in Poland the boy would address members of his extended family by formal titles reserved for strangers.

The same rings true for Szymon Pyszny, 43, a builder from Aberdeen whose fiancée and two young children have recently relocated to Poland. “We wanted the children to grow up near family, with their grandmas and grandads,” he says.

Difficult returns

While many Polish migrants, who moved to the UK during the post-2004 wave of EU immigration as young adults, have grown tired of the precarious migrant lifestyle and crave the comfort and stability of their home country, Czeranowska stresses that returns often prove short-lived or disappointing.

“For those used to living abroad, confronting Polish reality can be difficult,” she says. “30% [of research participants] said they want to emigrate again and 20% said they were unsure. Of those who want to emigrate, over 50% want to return to Britain.”

Pyszny had to give up hope of permanently moving to Poland with his partner and children as, despite over 15 years of experience as a builder, he had no formal qualification in the trade. “You can’t get a job in Poland without the right papers – no matter how good you are,” he says.

Realising that it would be impossible to find a position as senior as his job as a general foreman in Poland, he reached a compromise with his employer in Scotland to allow him to work full time in Aberdeen for six months and spend the remainder of the year in Poland with his family.

“Even though I’ll be earning half as much as before, it should be enough for us in Poland,” he says.

Białas, who worked as a baker in Poland before retraining as a builder in the UK, is also put off by the tendency of Polish employers to value formal qualifications over experience, although he is more confident about his future in the country due to the savings he and his partner prepared for their return. “You can’t come back without money,” he says.

However, it is not only the job market that many returnees find hard to navigate. “The most common complaint we had about life in Poland is actually the quality of customer service,” says Czeranowska, explaining that many returnees were dissatisfied with what they perceived as the rude and despondent attitude of shop assistants.

“The mentality in Poland is different,” says Sperkowska, who after returning to Poland began working as a shop assistant herself. “If you try chatting to strangers here, people give you funny looks.”

She has been trying to introduce some of the British retail sensibilities she picked up in Suffolk to her new workplace – starting with dropping the formal Pan (Sir) and Pani (Madam) titles wherever possible – but says that her efforts are often met with reluctance.

The relocation has also not been easy for her son. “He struggles with Polish,” says Sperkowska. “He doesn’t speak clearly and can’t form full sentences.” Borys also misses his old school friends back in Suffolk, with whom he stays in touch via online games.

He is not the only English-speaker in his new school, however. “There is another boy in his class who also just came back from the UK,” Sperkowska says. Two of Borys’s British-born cousins will also be joining the school in September. The children only speak with each other in English.

Confounding expectations

But while Poland may still present a challenging environment for lower-income families, the increasingly cosmopolitan profile of the country’s largest cities is attractive to young, educated Poles.

“I thought Warsaw was kind of like a giant Canary Wharf, but it is actually very hipster,” says Rabikowska, “while Kraków is a lot more international than I had expected it to be.”

Since settling in Krakow she has been working on new projects, interrogating Polish identity and experiences of other returnees. “I keep finding a lot of really great artists that perhaps no one outside of Poland has heard of, but they’re doing really exciting work,” she says.

She also finds the country less remote than Britain. “You don’t have this ‘island mentality’, things feel more connected,” she says. “I can just buy a train ticket and go to Berlin.”

But Poland’s country’s image abroad might not be transforming as quickly as its urban landscapes.

“My friend who is English moved to Poland recently, and his parents asked if he would have internet here,” Rabikowska says. When she told her friends that she had been vaccinated against the coronavirus earlier this year, one from the Netherlands asked if it was the Russian Sputnik vaccine.

Rabikowska sees her foreseeable future in Poland for work reasons, but stresses that “nothing is permanent”.

Meanwhile, Sperkowska and Białas are determined to stay in the country forever. On YouTube, Białas regularly posts updates from the building site of their home. However, he says, none of this would be possible if he and his partner had not worked in the UK.

“If we had not gone to England, we would be poor and living on credit,” a future which he hopes his son will be able to avoid.

“We are already putting money into an account for him. When he grows up, he’ll have savings, he’ll speak English, he’ll be able to live anywhere. Well… probably not in England, but anywhere else.”

Main image credit: Mateusz Skwarczek / Agencja Gazeta

A journalist for The Guardian, she has also written for The New Statesman, Prospect, and Notes from Poland. Previously studied journalism at Goldsmiths as a Scott Trust Bursary recipient.