By Nicholas Boston

Tomorrow marks the 76th anniversary of the beginning of the Warsaw Uprising. It was waged between 1 August and 2 October 1944, by the Home Army, the Polish resistance movement, to liberate Warsaw from Nazi German occupation.

Up to 50,000 people took part in the Uprising (sometimes called Rising), approximately 18,000 of whom were killed and another 25,000 wounded. Upwards of 200,000 civilians were also killed. Between 600,000 and 650,000 Varsovians ended up expelled from the city, with a sizeable number sent to Nazi concentration and labour camps.

An unknown hero

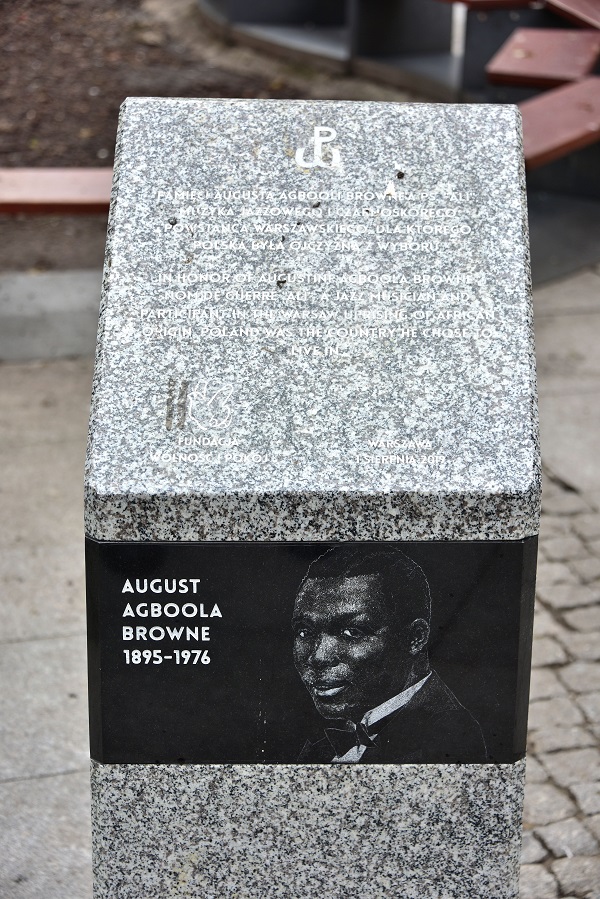

The veterans, living and deceased, of this 63-day-long operation are among Poland’s most heroised private citizens. As the nation, and Varsovians in particular, publicly commemorate this historic episode, the eyes of some will turn to a minimalist monolith of polished stone erected a year ago at this time in Warsaw’s Old Town.

The monument to August Agboola Browne in Warsaw (photo: Wikimedia)

It is a monument to a man named August Agboola Browne, who, as far as existing records can tell, was the only black insurgent in the Warsaw Uprising.

Arriving in Poland in 1922 from Nigeria, then a British colony, Browne became a celebrated jazz percussionist in 1930s Warsaw, known for his attractiveness and charisma. He joined the resistance movement from the time of the German invasion in 1939, and proceeded to fight in the Uprising under the code name “Ali”.

Until just a decade ago, Browne’s story was completely unknown. But from the moment of his introduction to the Polish public, he has been upheld in some quarters as not only a proud symbol of Poland’s past, but a promising model for its present and future.

“I had an obligation, a moral obligation, to write about Ali,” said Wojciech Karpieszuk, a journalist at Gazeta Wyborcza who wrote the first articles about Browne to appear in the mainstream press, back in 2010 and 2011.

“To say, ‘Look, he was a migrant, he came here and he became a part of the society.’ I was born in Białystok, in eastern Poland, and at the time when the story was published, there were many racist attacks in my hometown.”

“I think that Ali’s story is more important in today’s Poland than it was even ten years ago, because of the refugee crisis in 2015, and how it was used by the ruling party, Law and Justice (PiS), and other authorities. They used the migrants, the refugees, as scapegoats, and it’s also the same with the LGBT community now. We are used as scapegoats. I’m a supporter of a diverse society and I believe Ali’s story is a great example to show the advantages of diversity.”

Karpieszuk initially learned about Ali from a book titled Afryka w Warszawie, or “Africa in Warsaw”, published in 2010 by the Africa Another Way Foundation (Fundacja Afryka Inaczej), which was founded in 2008 to promote “knowledge sharing and communication” between Poles and Africans. The organisation’s co-founders, Mamadou Diouf, a professional musician and writer, and Dr Paweł Średziński, an historian and journalist, edited the volume.

“In 2009, just for fun, we were looking for the history of Africans in Poland,” Diouf said. “That is how it all started. At first, we didn’t think we were going to find anything. But in the end, we put out a 200-page book!”

A brief chapter in the book, “Insurgent from Nigeria”, is about Browne (there are several different spellings of his names in circulation), contributed by the historian Dr Zbigniew Osiński, an archivist at the Warsaw Rising Museum.

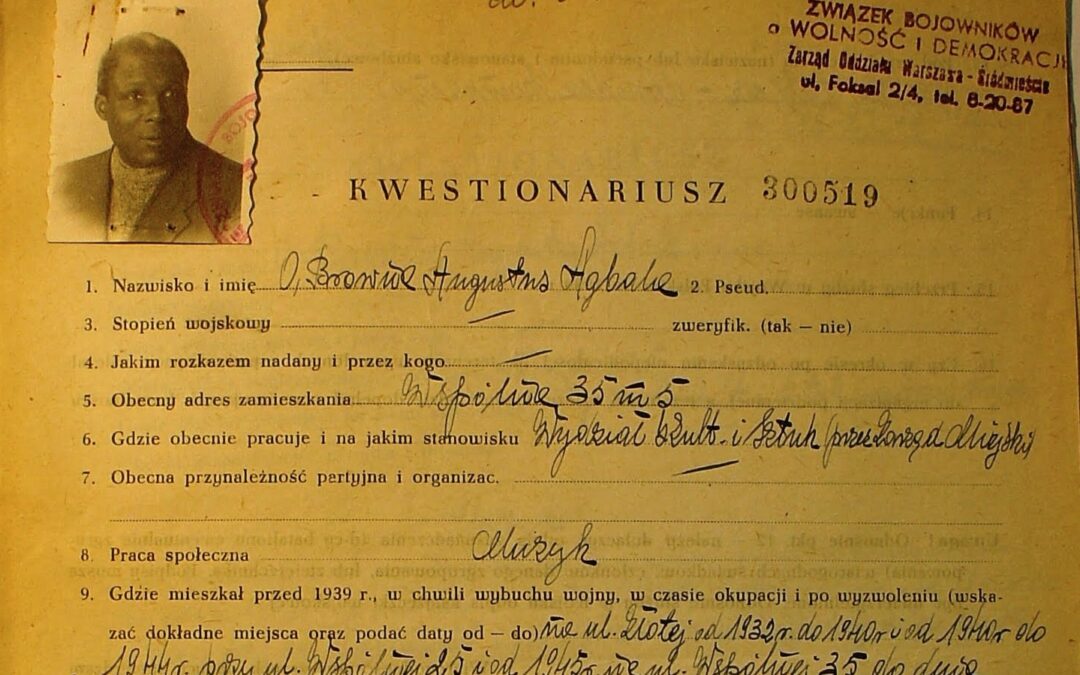

In 2008, Osiński had been in the process of compiling a dictionary of all known insurgents when he came across an application form Browne filed in 1949 for membership in the Society of Fighters for Freedom and Democracy (ZBoWiD), a veterans’ organisation.

The form bore all the applicant’s identifying information. Date and place of birth: July 22, 1895, Lagos, Nigeria. Parents’ names: Wallace and Józefina. Battalion: Iwo. Commanding Officer: Corporal Aleksander Marciński, code name “Łabędź” (“Swan”). Location of his operation: Śródmieście. Code name: Ali.

“This is a very interesting story, of this, our Nigerian,” Osiński said. “He was a citizen of Great Britain and Poland. We, as Poles, can ‘use’ his story. We can say there was a man who felt Polish and, furthermore, fought in the September Campaign (Invasion of Poland) in a voluntary battalion in the Ochota district of Warsaw, and later during the Warsaw Uprising. And he was an adult man by then, he was not a young boy. He was around 47 or 48, at least, not a youngster.”

“Sensation” and inspiration

“It was known that there were people of many nationalities that participated in the war,” said Diouf, a Polish citizen who came to Poland from Senegal as a student in 1983 and decided to make the country his home.

“But the Poles did not know that among them was an African. Above all, it was his participation in the Uprising that propelled Agboola to centre stage. If he had been just a musician, nobody would really be interested in him.”

Diouf and Średziński went to great lengths to publicize the story. Diouf recalled that for one television interview “we invited a Tanzanian friend to impersonate Agboola” for dramatic effect, noting that, fanfare aside, the public was captivated by the news. “For the Polish people, this represented something extraordinary,” he said.

Academics who had written reams about the Warsaw Uprising found the Ali story “a sensation”, as military historian Dr Krzysztof Komorowski told Karpieszuk.

Among younger Poles, Browne inspired an array of creativity. The visual artist Karol Radziszewski produced a series of paintings titled “Ali”, two of which were purchased by the Museum of Warsaw. Radziszewski also sketched Syrenka, the mermaid symbol of Warsaw, reimagined as Ali, brandishing a hammer and tribal shield instead of the traditional sword and round shield. At the exhibition’s opening in 2016, all the merchandise bearing the Ali Syrenka image “sold out in one hour”, Radziszewski told me.

That same year, an experimental music ensemble named “The D.N.Acid Rock” released an instrumental composition on YouTube entitled “31 July 1944. Dedicated to August Agbola O’Brown”. And, in 2018, Dr Asia Jasitczak, an historian whose quirky videos on her YouTube channel “Satyrycznie Historycznie” (“Satirically Historically”) explain events in history using theatrical flourishes, posted an instalment about Browne in which she and a friend impersonated him and his first wife.

Life in pre-war and wartime Poland

Browne twice married Polish women, and fathered four children. His first marriage, to Zofia Pykówna, in Kraków in 1925 or ’26, was such a rarity that it drew the attention of a newspaper, which published a photograph of the wedding party with the caption “A Black-and-White marriage…that took place in Kraków, where authentic Negro (autentyczny murzyn), Mr. August Braoun [sic], married authentic Polish woman, Ms. Zofia Pykówna. The exotic wedding gathered crowds in church.”

The Brownes had two sons, Ryszard, born in 1928, and Aleksander, born 1929, but their marriage soon failed. At the outbreak of war, Zofia and the boys, as the wife and children of a British citizen, had the right to be evacuated to the UK, and left besieged Poland.

Ali himself remained to fight. He served in the Home Army primarily by relaying intelligence with his fluent Polish. He also taught English and traded in electronic equipment. He miraculously survived World War II, emerging among the barely 6% of Warsaw’s pre-war citizenry that remained present and alive.

In 1949, he worked in the Department of Culture and Art of the City of Warsaw, and gradually resumed performing jazz. In 1953, he was cast in a non-speaking role in the film Soldier of Victory (Żołnierz zwycięstwa), directed by Wanda Jakubowska.

Diaspora life and nation-building

In 1952 or ’53, he remarried, to Olga Miechowicz, who was 20 years his junior. The couple moved to Paris in 1956, then on to the United Kingdom in 1958, where they settled permanently. In 1959, their daughter, Tatiana, was born. An older daughter of Browne’s, Beata Brown-Łuczak, resides in Poland.

Of Browne’s existence in the UK, Tatiana informed me that her father continued to work as a percussionist in London, often at a studio in the Soho district, the home of London’s jazz and swing music scene. The family resided in Camden Town, northwest London.

“My daddy?” Tatiana said when asked whether she had grown up with her father. “I lived with him. He raised me.”

Had she seen the monument to her father? “Yes, I was there last year and I saw it,” she said. “It was very nice to see that he was remembered in such a way.”

In London, Browne was at the meeting place of several diasporas to which he belonged equally. By the 1960s, London, and the UK in general, had become home to a sizeable black population, most of whose members were migrants from the Caribbean, the so-called Windrush generation, with Africans from former British colonies on the continent adding to their numbers. There was also a large Polish community, comprising demobilised servicepeople and their families, refugees and expatriates.

Londoner Ela Grabinska-Raubusch, an affiliate of the Sikorski Institute, recalls her late mother, Wanda Grabińska (née Radzikowska), a Warsaw insurgent, speaking about Browne. “My mother said that he was very famous in Warsaw before the war, since he was probably the only black person in the capital,” she said.

“As for his insurgent career, I only know what I’ve read online. Except, coincidentally, he was in Śródmieście Południe, and so was my mother. She was in the Ruczaj battalion. Mum came to London in 1957. I understand that Mr Browne came in 1958.

“Mum did talk about how she met Mr Browne, and that he was with his daughter. Either at Shepherd’s Bush Market or at the office of [a man named] Mehl, who dealt with transfers of money to Poland in the years 1950 to 1980. We lived in Shepherd’s Bush for a while. In the 1960s, Shepherd’s Bush Market was the hangout for the Caribbean community. The stalls were run by West Indians and various Polish Jews. My mother didn’t speak English, so she could go ahead and buy from them in Polish.”

Browne was again at the centre of a nation-building project, this time of migrants like himself reconstituting Great Britain. With most first-person acquaintances and witnesses such as Wanda Grabińska already departed, Browne’s London life becomes increasingly challenging to reconstruct with complete accuracy.

Browne passed away from cancer on 8 September 1976 at the age of 81. He lies at rest in London’s Hampstead Cemetery. In 2017, his gravestone was located, cleaned and polished by the London club of Against the Tide TV (Idź Pod Prąd TV), a pro-creationism Polish media outlet that reports news from “the biblical perspective”.

In a press release, the organisation’s founder Pastor Paweł Chojecki cited this action as proof that it was not racist, as widely reported in both Poland and the United Kingdom. A prominent figure associated with the group is Marian Kowalski, who stood as a candidate for the far-right National Movement in the 2015 Polish presidential election.

Browne’s gravestone stands as one bookend of his remarkable journey through modern European history. The other bookend is, of course, his monument in Warsaw’s Old Town.

“Choose a place and identify with that place”

The 1.2 metre-high monument, the brainchild of Jarema Dubiel, director of the Freedom and Peace Movement Foundation, was unveiled on 2 August 2019. On its sloping top is inscribed, in both Polish and English, “In honour of Augustine Agboola Browne. Nom de guerre, ‘Ali’, a jazz musician and participant in the Warsaw Uprising of African origin. Poland was the country he chose to live in.”

“When I think of Ali, I think of Polonia, the Polish diaspora,” Diouf said. “There are between 10 and 20 million people around the world who regard themselves as Polish, who follow Polish traditions, practise Polish culture. They don’t have to. They are people whose parents or grandparents left Poland fifty, one hundred years ago, to Australia, to the USA, to Brazil, to South Africa. This is what I say when I get into debates with people who oppose immigration. You can’t deny this. You do the same in other countries. It’s human nature. I choose a place and I identify with that place. If that place encounters a problem, I work with the people to resolve that problem. That’s it.”

Wojciech Załuski provided research assistance for this article.

Main image credit: Warsaw Rising Museum