For the first time in English, Notes from Poland presents a newly discovered short story – entitled “Undula” – by Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz (1892-1942), translated with a short introduction by Stanley Bill.

The Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz left only two collections of short stories and a few scattered essays behind when he was murdered by an SS officer in his home town of Drohobycz in 1942.

Since his death, the legend of a great lost work, a novel entitled The Messiah, has inspired international investigations and even new works by Philip Roth, Cynthia Ozick, and other writers. To this day, The Messiah has never been found, and there is no certainty that it ever existed. But an exciting discovery has recently been made in Schulz’s native region, today in western Ukraine.

Late last year, in an archive in Lviv, a Ukrainian researcher named Lesya Khomych found a strange story in an obscure Polish oil industry newspaper from 1922. Entitled “Undula,” the story follows the masochistic sexual imaginings of a sick man confined to his bed in a room inhabited by whispering shadows and cockroaches. Khomych immediately suspected that Schulz might be the author, though the work appeared under the unknown name of Marceli Weron. Leading experts in Poland soon confirmed her hypothesis.

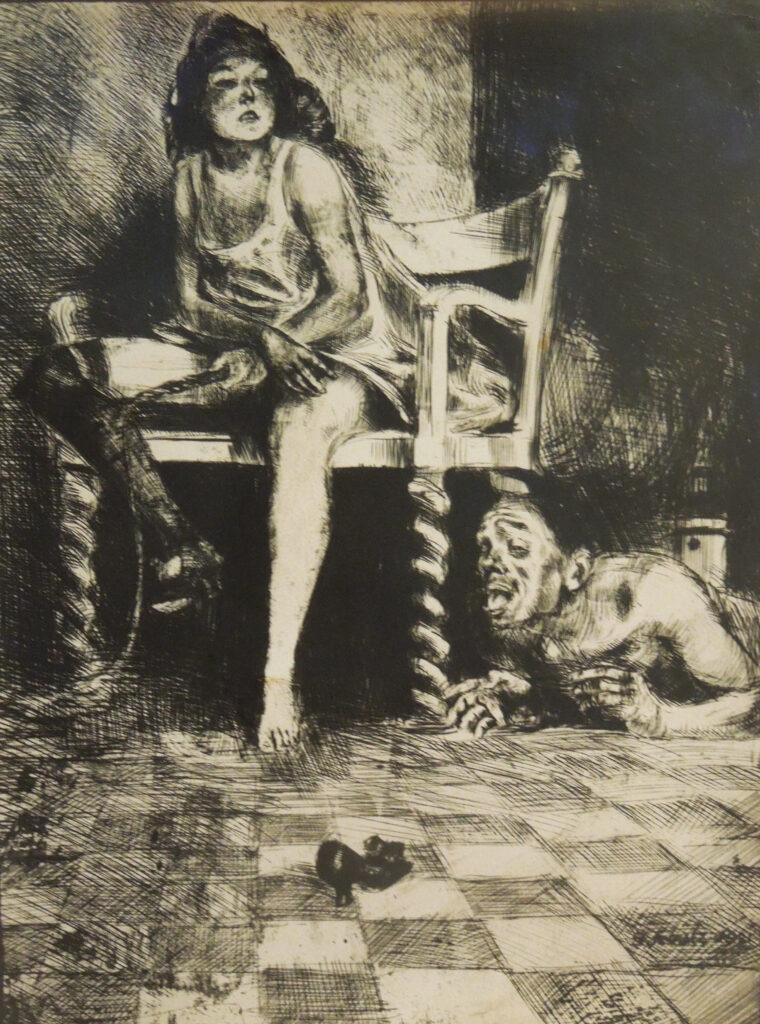

Though there can be no definitive proof, the story is almost certainly Schulz’s, published under a pseudonym more than a decade before his first known works came out in 1933. The titular “Undula” is a name Schulz invented for a young woman central to the masochistic sexual mythology of his drawings of the early 1920s. He produced multiple images of an “Undula” closely fitting the descriptions of the story – a sultry demigoddess spurning the protagonist who worships her.

Other distinctive references anticipate characters from Schulz’s later stories: a haughty maidservant called Adela, a “Demiurge” creator, crablike cockroaches, and a sickly protagonist in solitary confinement.

The richly figurative style of the story is also unmistakable, though an uneven quality reflects its experimental status. Schulz’s best writing takes aesthetic risks, as he exuberantly piles metaphor upon metaphor. In this early sketch, the result is sometimes awkward or repetitive. Certain meanings remain obscure. Yet the story also contains brilliant passages and stunning new elements that expand our understanding of Schulz.

“Undula” is more frankly sexual than the later stories, which are mostly told from the perspective of a child. Here the adult narrator creates an atmosphere closer to Schulz’s erotic drawings, obsessively filled with images of the artist himself groveling at the feet of lithe young women. The new story almost forms a missing link between the graphical and literary phases of his creative life.

An oil industry newspaper seems a strange place for the original publication of this surrealist work in 1922. The connection here might have been Schulz’s elder brother, Izydor, who worked in the oil business that dominated the Drohobycz area. He could have facilitated the publication, with the pseudonym necessitated by his (or Bruno’s) embarrassment at the story’s candidly sexual content.

A decade later, in 1933, Izydor bankrolled his brother’s first published volume of stories, Cinnamon Shops (Sklepy cynamonowe). Perhaps incongruously, it was the oil money of Schulz’s native region that underwrote the poetic flights of his literary works.

The discovery of what is probably Schulz’s earliest published story opens the tantalizing possibility that he might have published other works under pseudonyms. Polish and Ukrainian researchers are currently combing through archives in both countries for further traces. Almost eighty years after his murder in the Holocaust, the image of Bruno Schulz’s life and work could be very far from complete. With the revelation of a new deity in “Undula,” there may yet be hope for those still waiting for The Messiah.

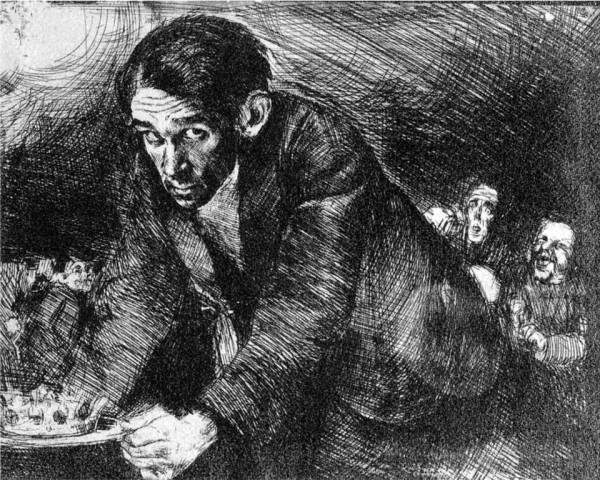

Self-portrait, Bruno Schulz

Undula

By Marceli Weron [Bruno Schulz]

Translated by Stanley Bill

It must be weeks or months now that I’ve been locked in this solitude. I keep falling into sleep and then waking again, so that phantoms of wakefulness become tangled with figments of the somnolent darkness. And so time passes. It seems to me that I’ve lived in this long, crooked room before, in some distant past. Sometimes I recognize the oversized furniture that stretches up to the ceiling, these plain oak wardrobes bristling with dust-covered junk. A large, multi-armed tin lamp hangs from above, swaying gently.

I lie in the corner of a long yellow bed, my body barely filling even a third of its expanse. There are moments in which the room, illumined by the yellow light of the lamp, seems to vanish from my sight. In a heavy lethargy of thought, I feel only the calm, powerful rhythm of my breath, as it raises my chest in a regular beat. In harmony with this rhythm comes the breath of all things.

Time oozes away with the vapid hissing of the oil lamp. The old furniture cracks and creaks in the silence. Shadows lurk and conspire in the depths of the room – jagged, crooked, and broken. They stretch out their long necks and peer at me through their arms. I don’t turn over. What for? As soon as I look, they will all be quiet in their places again, and only the floor and the old wardrobe will creak and groan. Everything will be still, unchanged, like before. Once more there will be silence, and the old lamp will sweeten its boredom with a sleepy hiss.

Great, black cockroaches stand motionless, staring vacantly into the light. They seem dead. All of a sudden, those flat, headless bodies take off in an uncanny crablike run, cutting diagonally across the floor.

I sleep, wake, and then doze off again, patiently pushing my way through sickly thickets of phantoms and dreams. They become tangled and intertwined as they wander along with me – soft, milky, luxuriant bushes, like the pale nocturnal sprouts of potatoes in cellars, like monstrous growths of diseased mushrooms.

*

Perhaps out in the world it’s already spring. I don’t know how many days and nights have passed since that time… I remember that gray, heavy dawn of a February day, that purple procession of Bacchantes. Through what pale nights of revelry, through what moonlit suburban parks did I not fly after them, like a moth bewitched by Undula’s smile. And everywhere I saw her in the shoulders of the dancers: Undula, languid and leaning enticingly in black gauze and panties; Undula, her eyes afire behind the black lace of a fan. And so I followed her with a sweet, burning frenzy in my heart, until my swooning legs would carry me no further and the carnival spat me out, half-dead, on some empty street in the thick gloom before dawn.

Then came those blind wanderings, with sleep in my eyes, up old staircases climbing through many dark stories, crossings of black attic spaces, aerial ascents through galleries swaying in the dark gusts of wind, until I was swallowed up by a quiet, familiar corridor, and found myself at the entrance to our apartment of my childhood years. I turned the handle, and the door opened inward with a dark sigh. The scent of that forgotten interior enfolded me. Our maidservant Adela emerged from the depths of the apartment, padding noiselessly on the velvet soles of her slippers. How she had blossomed in beauty during my absence, how pearly white her shoulders were under her black, unbuttoned dress. She was not the least bit surprised by my return after all these years. She was sleepy and brusque. I could make out the swan-like curves of her slender legs as she disappeared back into the black depths of the apartment.

I groped my way through the half-light to an unmade bed and, eyes dimming with sleep, plunged my head into the pillows.

Dull sleep rolled over me like a heavy wagon, laden with the dust of darkness, covering me with its gloom.

Then the winter night began to wall itself in with black bricks of nothingness. Infinite expanses condensed into deaf, blind rock: a heavy, impenetrable mass growing into the space between things. The world congealed into nothingness.

*

How difficult it is to breathe in a room caught in the pincers of a winter night. Through the walls and ceiling one can feel the pressure of a thousand atmospheres of darkness. The air is barren, lacking nourishment for the lungs. The light of the lamp is overgrown with black mushrooms. One’s pulse becomes faint and shallow. Boredom, boredom, boredom. Somewhere deep in the solid mass of the night, lone wayfarers walk along the dark corridors of the winter. Their hopeless conversations and monotonous tales seem to reach me. Undula reposes in her fragrant bed in a deep slumber that sucks out of her the memory of the orgies and frenzies. Her limp, soft body – peeled out of the confines of gauze, panties and stockings – has been snatched up by the darkness, which clutches her in four enormous paws, like a great furry bear, gathering her white, velvety limbs into one sweet handful, over which it pants with purple tongue. And she, unresponsive, her eyes in distant dreams, numbly gives herself over to be devoured, while her pink veins pulsate with milky ways of stars, drunk in by her eyes on those vertiginous carnival nights.

Undula, Undula, o sigh of the soul for the land of the happy and perfect! How my soul expanded in that light, when I stood, a humble Lazarus, at your bright threshold. Through you, in a feverish shiver, I came to know my own misery and ugliness in the light of your perfection. How sweet it was to read from a single glance the sentence condemning me forever, and to obey with the deepest humility the gesture of your hand, spurning me from your banqueting tables. I would have doubted your perfection had you done anything else. Now it’s time for me to return to the furnace from which I came, botched and misshapen. I go to atone for the error of the Demiurge who created me.

Undula, Undula! Soon I will forget you too, o bright dream of that other land. The final darkness and the hideousness of the furnace draw near.

*

The lamp filters the boredom, hissing its monotonous song. I seem to have heard it before, long ago, somewhere at the beginning of life, when as a sickly, forlorn infant I fussed and fretted through tearful nights. Who then called out to me and brought me back as I blindly sought the path of return to maternal, primordial nothingness?

How the lamp smokes. The gray arms of the candelabra have sprung out of the ceiling like a polyp. The shadows whisper and plot. Cockroaches scuttle noiselessly across the yellow floor. My bed is so long that I can’t see its other end. As always, I am ill, gravely ill. How bitter and filled with abomination is the road to the furnace.

Then it began. These monotonous, futile dialogues with pain have utterly worn me down. Endlessly I argue with it, adamant that it can’t reach me as pure intellect. While everything else becomes muddled and clouded, I feel ever more clearly how he – the suffering one – is separated from my watching self. And yet at the same time I feel the delicate tickle of dread.

The flame of the lamp burns ever lower and more darkly. The shadows stretch their giraffes’ necks up to the ceiling; they want to see him. I hide him carefully away under the quilt. He is like a small, shapeless embryo without face, eyes or mouth; he was born to suffer. All he knows of life are those forms and monstrosities of suffering that he meets in the depths of the night in which he is plunged. His senses are turned inward, greedily absorbing pain in all its varieties. He has taken my sufferings upon himself. Sometimes it seems he is nothing but a great swim bladder inflated with pain, the hot veins of suffering upon its membranes.

Why do you weep and fuss the whole night through? How can I ease your sufferings, my little son? What am I to do with you? You writhe, sulk, and scowl; you cannot hear or understand human speech; and yet still you fuss and hum your monotonous pain through the night. Now you are like the scroll of an umbilical cord, twisted and pulsating…

*

The lamp must have gone out while I dozed. It’s dark and quiet now. Nobody weeps. There is no pain. Somewhere deep, deep in the darkness, somewhere beyond the wall, the drainpipes chatter. Lord! It’s the thaw!… The attic spaces dully roar like the bodies of enormous musical instruments. The first crack must have formed in the solid rock of that black winter. Great lumps of darkness loosen and crumble in the walls of the night. Darkness pours like ink through those fissures in the winter, muttering in the drainpipes and sewers. Lord, the spring is coming…

Out there in the world, the town slowly releases itself from manacles of darkness. The thaw chisels out house after house from that stone wall of darkness. O, to draw in the dark breath of the thaw with my breast again; o, to feel upon my face the black, moist sheets of wind sweeping down the streets. The little flames of the lamps on the street corners shrink into their wicks, turning blue as those purple sheets of wind fly around them. O, to steal away now and escape, leaving him here alone forever with his eternal pain… What base temptations do you whisper into my ear, o wind of the thaw? But in what neighborhood of the town is that apartment? And where does that window face, knocked by its shutter? I can’t remember the street of my childhood home. O, to look out that window and to meet the breath of the thaw…

Marceli Weron, “Undula,” Świt. Organ urzędników naftowych w Borysławiu, no. 25-26 (15 January 1922), pp. 2-5. Republished in Schulz/Forum 14 (2019), edited by Piotr Sitkiewicz.

Main image: Spotkanie. Żydowski młodzieniec i dwie kobiety w zaułku miejskim by Bruno Schulz (public domain)

Stanley Bill is the founder and editor-at-large of Notes from Poland. He is also Professor of Polish Studies and Director of the Polish Studies Programme at the University of Cambridge. He has spent more than ten years living in Poland, mostly based in Kraków and Bielsko-Biała.

He is the Chair of the Board of the Notes from Poland Foundation.