A small community in northern Poland is embroiled in a dispute over 13 wooden sculptures of spirits based on local folklore, pitting Catholics warning of “demonic idolatry” against officials seeking to promote tourism. Some of the statues are set to be removed as a result.

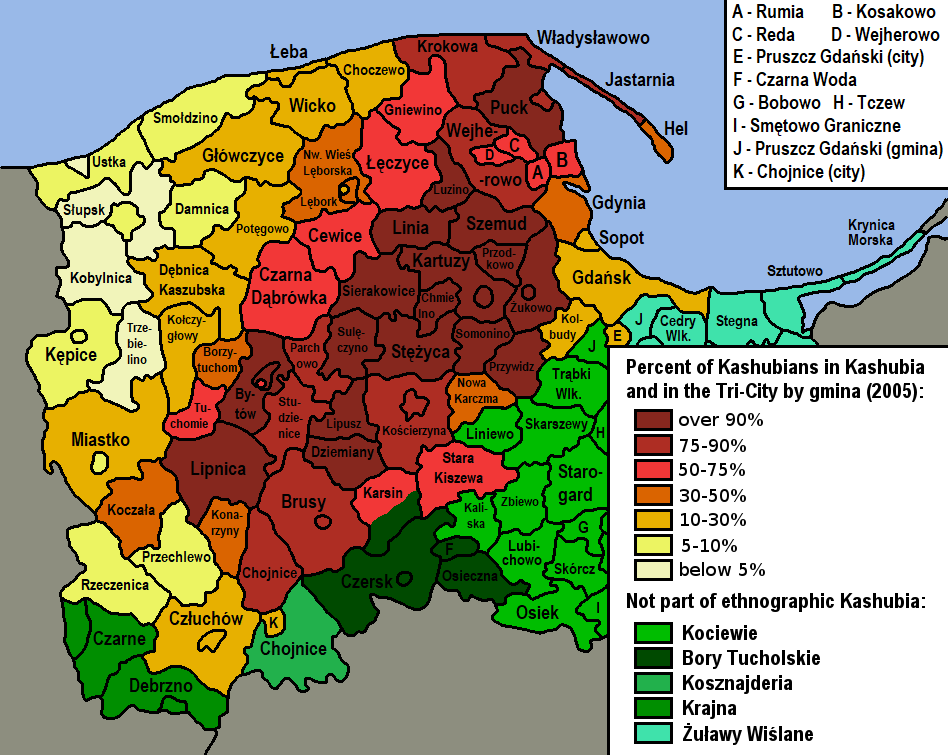

In 2010, the Linia commune – part of the region home to the Kashubs, an ethnic and linguistic minority group – created an 86 km tourist trail called “feel the Kashubian spirit” that runs between 13 villages. The project was supported by EU funds.

Each stop along the route is marked by a statue of a figure drawn from local mythology, including both benevolent spirits and also demons. But after a decade, the sculptures have started to fall into disrepair.

Yet when the issue of renovating them was taken up by a local council last year, residents put forward petitions calling the sculptures “pagan idols of devils” and claiming that they are “the main reason…for the renunciation of faith in our Catholic commune”, reported Gazeta Wyborcza.

One local priest argued that the sculptures belong in a museum. “Placing them in a public space is a form of idolatry and worship of…demons,” he said. “The world of Satan is real and his actions can be seen in the modern world.”

“In Greece or Rome, the faithful do not erect monuments to gods from mythology,” said another priest, quoted by Gazeta Wyborcza.

Kilkanaście lat temu na terenie gminy Linia stanęło 13 drewnianych figur w ramach szlaku „Poczuj kaszubskiego ducha”. Przybliżały one bogactwo naszej kultury, stanowiły też swoistą atrakcję turystyczną. Po renowacji miały wrócić na swoje miejsce, stało się jednak inaczej.

… pic.twitter.com/HeYcwloyo9— Jack #CSB (@zKaszebe) February 4, 2020

In response, the mayor of one of the villages, Bogusława Engelbrecht, reassured that “no one is using [the sculptures] to fight Kashubs or their faith”.

They are simply a “tourist product” that “promotes the commune, [its] beautiful surroundings and a writer hailing from here, Aleksander Labuda”, said the mayor.

Made by folk artist Jan Redźko, the sculptures are based on a book about local mythology compiled by Labuda. Speaking at a council meeting, the author’s daughter said she felt sad and embarrassed that the tourist trail based on her father’s work could be dismantled.

She compared the sculptures to the central statue of Neptune in the nearby seaside city of Gdańsk. She also pointed to the prevalence of Greek mythological figures (Hades, Tanatos, Cerber) in the names of Polish funeral homes, as well as to a popular supermarket, Lewiatan, named after the biblical demon.

Scott Simpson, a lecturer in religious studies at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and expert on Polish paganism, told Notes from Poland that “the 13 figures have been selected because they are very local. They belong to stories collected in that area, ethnographically, as an expression of local pride”.

“Amongst the voices complaining about the removal, there are people interested in local folklore,” with no strong religious motivations, added Simpson. Yet “other people amongst them would be Contemporary Pagans, who are religiously offended by the things being taken down.”

Contemporary Pagans in Poland are small in number but “relatively visible, for example, in the folk music scene,” according to Simpson. In Poland, there may be “in the order of 2,500 very active participants in Slavic Native Faith (Rodzimowierstwo)” and a “much broader range of people” who sometimes participate.

“They do not like to see their local folklore removed, which is to them sacred,” said Simpson. And they worry about “seeing that some religions can be put up on a pedestal, but the folk religion is sent away to be put in a museum,” as the local parish priest suggested.

Starowierstwo Morzan (Old Believers of the Sea), a community group which has been promoting a petition to keep the sculptures, wrote on Facebook: “Kashubs remain Kashubs because they cultivate their customs, rites, and beliefs of their ancestors.”

Kashubs are recognised as an ethnic minority within the Polish state. Their region in the north of the country is loosely delineated by the use of Kashubian language – a Slavic dialect close to Polish but with Low German influences – which is spoken by around 100,000 people as their main language at home.

To settle the dispute over the sculptures, each of the 13 villages is now holding a vote on the fate of their own one. On Wednesday, residents of Linia chose to get rid of their sculpture of Rétnik, a spirit said to tempt local musicians with enchanted instruments, especially during Lent and Advent, when festivities are restricted.

Some residents took issue specifically with the carvings of malevolent spirits, with one saying: “Each village has its guardian angel. Putting up a demon does the opposite.”

Those living in Niepoczołowice and Kętrzyno have also chosen to get rid of their carving of Nëczk, an evil water spirit believed to create whirlpools dangerous to swimmers, and Wëkrëkùs, patron of recluses. In Osiek, the wooden statue of Jablón, a orchard-inhabiting spirit who allegedly steals fruits and vegetables, has already been replaced by a figure of Christ the King.

But some villages have chosen to go the other way. Residents of Smażyn and Strzepcz have decided to keep their carvings of Grzenia, guardian of dreams, and Bòrowô Cotka, patron of forest animals.

The others are yet to decide. The spirits whose fate is still on the line include Jigrzan, patron of fun and dance, who is celebrated on Kupala Night (Sobótka), the shortest night of the year. Tłuczewo will vote on its goddess Pólnica, who is believed to ride a horse naked through the fields, tending the crops.

Pobłocie will decide on its carving of Szëmich, the benevolent spirit of silence, and Kobylasz-Potęgowo on Lubiczk, patron of love and sex. Lewino will have a say on Pikòn, a demon inflicting disabilities on people, and Miłoszewo on Damk, the spirit of secrets, who is said to liaise with taciturn people.

Finally, Lewink will mull over its sculpture of Pùrtk, demon of quarrels, who is thought to reside in garbage and manifest his presence through stench.

Kashubian Poles: Struggling with the “fifth column” labelhttps://t.co/BwI36KV63Y

— New Eastern Europe (@NewEastEurope) March 20, 2019

Main image credits: Titës/Wikimedia Commons (under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Maria Wilczek is deputy editor of Notes from Poland. She is a regular writer for The Times, The Economist and Al Jazeera English, and has also featured in Foreign Policy, Politico Europe, The Spectator and Gazeta Wyborcza.