Poland has again performed highly in the latest annual English Proficiency Index produced by EF Education First.

It received the top grade of “very high proficiency”, ranking 11th in the world and ninth in Europe, ahead of Portugal and Belgium but just behind Germany. The Netherlands topped the rankings, followed by the Scandinavian trio of Sweden, Norway and Denmark.

The Polish capital, Warsaw, also came tenth in EF’s ranking of cities, ahead of Lisbon. Amsterdam, Stockholm and Copenhagen took the top three places respectively.

The results represent a return to a “very high” rating after three years in which Poles were assessed as having “high proficiency”. Poland achieved its highest placing, sixth, in 2014, when there were only 63 countries ranked. The new figures include 100 countries, the largest number to date.

Poland’s results revealed some regional differences, with the Mazovian province, where the capital Warsaw is situated, ranked highest, followed by other regions containing large cities.

The difference between men and women’s results was minimal in Poland (with proficiency scores of 63.74 and 63.77 respectively), although in Europe overall women fared noticeably better.

Poland’s high position in the English Proficiency Index follows recent news that the country’s education system was rated among the best in Europe in the latest international PISA rankings.

Poland has continued its rise towards the top of the PISA education rankings, where it is now third in Europe for maths and science and fourth in reading comprehension https://t.co/Qt9l9wfCdo

— Notes from Poland ?? (@notesfrompoland) December 3, 2019

As noted by The Economist, however, while the EF report makes for interesting reading, it is “not entirely scientific”. The index is based on a voluntary, self-administered online test, and therefore requires internet access and willingness from participants.

Results are therefore skewed in favour of rich countries with an interest in English, and many African countries, for example, did not have enough test-takers to be included.

Adam Musiał, an educator with more than two decades’ experience of teaching English to high-school students in Kraków, told us that he is not surprised by Poland’s good performance.

“When I began teaching in the 1990s, private schools had begun to set new standards with pioneering changes, and public schools found themselves having to catch up,” he says. “It was realised that Poland needed to learn English fast if it was to participate and communicate with the world,” he says.

“There was a mass movement to introduce smaller groups, new methodology, and more efficient techniques,” adds Musiał. “Children started to be taught earlier, often two [foreign] languages, and there was a switch to using British coursebooks, with the participation of Polish educators, and an increased focus on communication skills.”

These trends have improved the economic prospects of both individual learners and Poland as a country. “In Kraków, for example, you can’t get a job in many sectors without knowing English,” notes Musiał. “It’s difficult to find a young person today unable to explain at least simple things in English.”

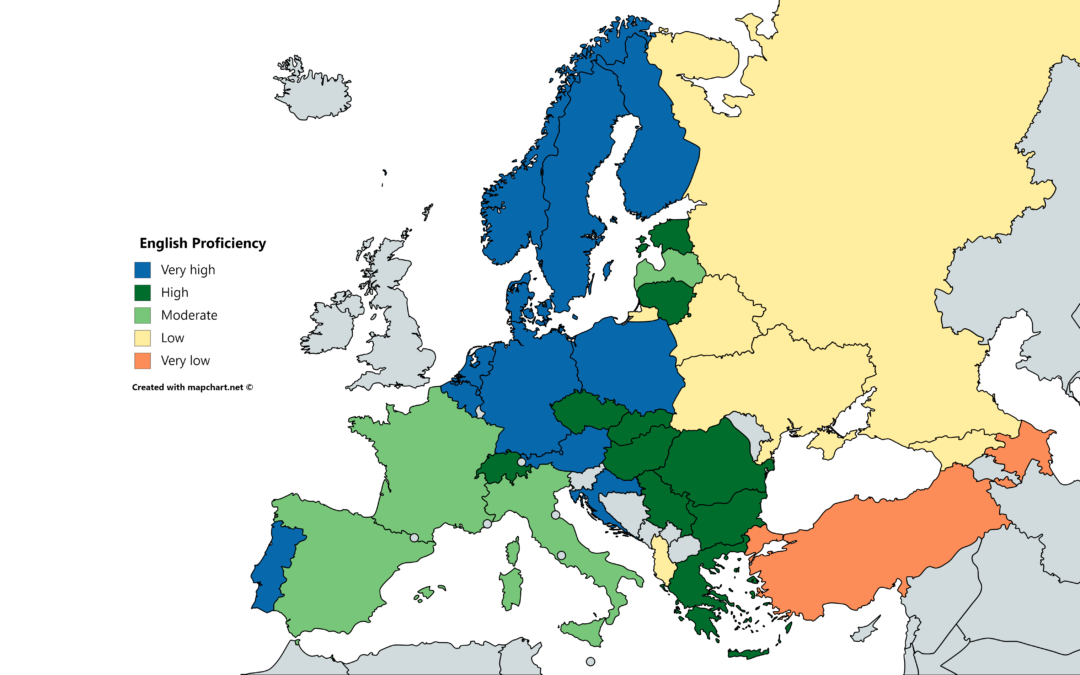

Main image credit: data from EF English Proficiency Index and map created through mapchat.net (under CC BY-SA 4.0)

Ben Koschalka is a translator and senior editor at Notes from Poland. Originally from Britain, he has lived in Kraków since 2005.