Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

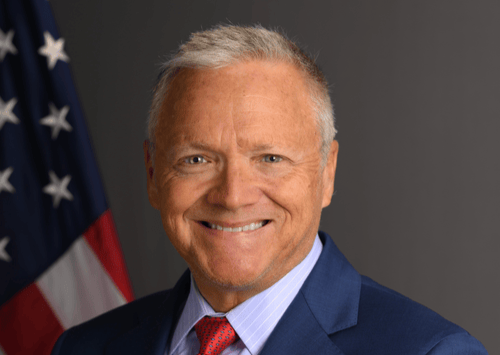

President Karol Nawrocki has vetoed a bill that would have recognised Silesian – which is spoken by hundreds of thousands of people from the historical area of Silesia in southwest Poland – as an official regional language.

Nawrocki argued that linguists consider Silesian to be a dialect rather than a separate language. He also said that he would not support any measures “that may create artificial divisions in our national community”.

Oświadczenie Prezydenta RP Karola Nawrockiego 🇵🇱 pic.twitter.com/L1TRuHbWkL

— Kancelaria Prezydenta RP (@prezydentpl) February 12, 2026

The president’s veto, which had been expected, marks a second failed attempt by the ruling coalition to recognise Silesian as a regional language. A previous bill to that effect was in 2024 vetoed by then-President Andrzej Duda, who like Nawrocki is aligned with the right-wing opposition.

In the most recent national census, around 460,000 people in Poland said they use Silesian as their main tongue at home. That is far more than the 87,600 who speak Kashubian, a language native to northern Poland that is currently the country’s only recognised regional language.

Such official recognition allows a language to be taught in schools and used in local administration in municipalities where at least 20% of the population declared in the last census that they speak it. It also provides additional funding for preserving the language.

While many linguists have traditionally viewed Silesian as a dialect of Polish, a growing number now argue that it is becoming a language in its own right. They point to its increasing standardisation, expanding body of literature and wider everyday use.

During work on the bill, Katarzyna Kłosińska, chair of the Council for the Polish Language, told lawmakers that circumstances have changed significantly since her council’s opinion helped classify Silesian as a dialect in 2011.

“At that time, the language or ethnolect was far less standardised. There was little literature, and fewer people saw it as their native, family or home language,” she said, quoted by the Polish Press Agency (PAP).

She also noted that, when Kashubian was granted regional language status in 2005, it was less standardised and had less literature and cultural presence than Silesian has today. For that reason, she argued, Silesian should also qualify for legal recognition.

Silesian, which is spoken in southwest Poland, has been added as a language on Google Translate.

The decision comes shortly after Poland’s own president vetoed a law recognising Silesian as a language. He says it is actually a dialect of Polish https://t.co/mXhmFgbchU

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 30, 2024

Nawrocki, however, has rejected that position. “We need to listen to what specialists say on this matter. Experts and linguists point out that Silesian is a dialect of Polish. We cannot create a precedent in which a political majority decides academic matters,” he said.

The president added that he “will not agree to solutions that could create artificial divisions within our national community”. Conservatives in Poland have long warned that some Silesian activists are seeking autonomy for their region from Poland.

However, Nawrocki emphasised that he “respects and greatly values Silesian tradition and culture” and would sign separate legislation, which has been submitted to parliament, supporting Silesian culture and dialect.

Similar arguments were used by Duda to justify his veto in 2024. He said that Silesian is not a language and even claimed that recognising it could threaten Poland’s security by undermining national identity.

The president’s decision to veto a law recognising Silesian as a language has reignited a debate that is ostensibly linguistic but at its heart is a struggle over culture, identity and, for some, the integrity of the Polish state itself https://t.co/HNgQ2436G7

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 9, 2024

Those claims have, however, been rejected by figures from the centrist Civic Coalition (KO), Poland’s main ruling party.

“Recognising Silesian does not threaten the unity of the state,” said Danuta Jazłowiecka, a KO MP from Silesia, in January, when parliament approved the bill. “On the contrary, it strengthens it, showing that the republic is a community that is open, respecting its internal richness and diversity.”

Nawrocki’s veto drew anger from another Silesian KO politician, MEP Łukasz Kochut, who told PAP that “the president spat in the face of hundreds of thousands of Silesians..[and] behaved like a complete prick”, using a Silesian expletive “ciul”.

Dobrze, że moja Babcia Irena nie dożyła dnia, w którym kolejny raz Prezydent Polski, mowi, że język, w którym mówiła, śpiewała, rzykała nie istnieje.

To jest kwestia godności❗️Polski szowinizm na razie zwyciężył. Na razie.

My som u sia🟨🟦. #slonskogodka #językśląski pic.twitter.com/CTzi5QEIxw— Łukasz Kohut 🇪🇺 (@LukaszKohut) February 13, 2026

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Anna Lewanska / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.