Keep our news free from ads and paywalls by making a donation to support our work!

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and is published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

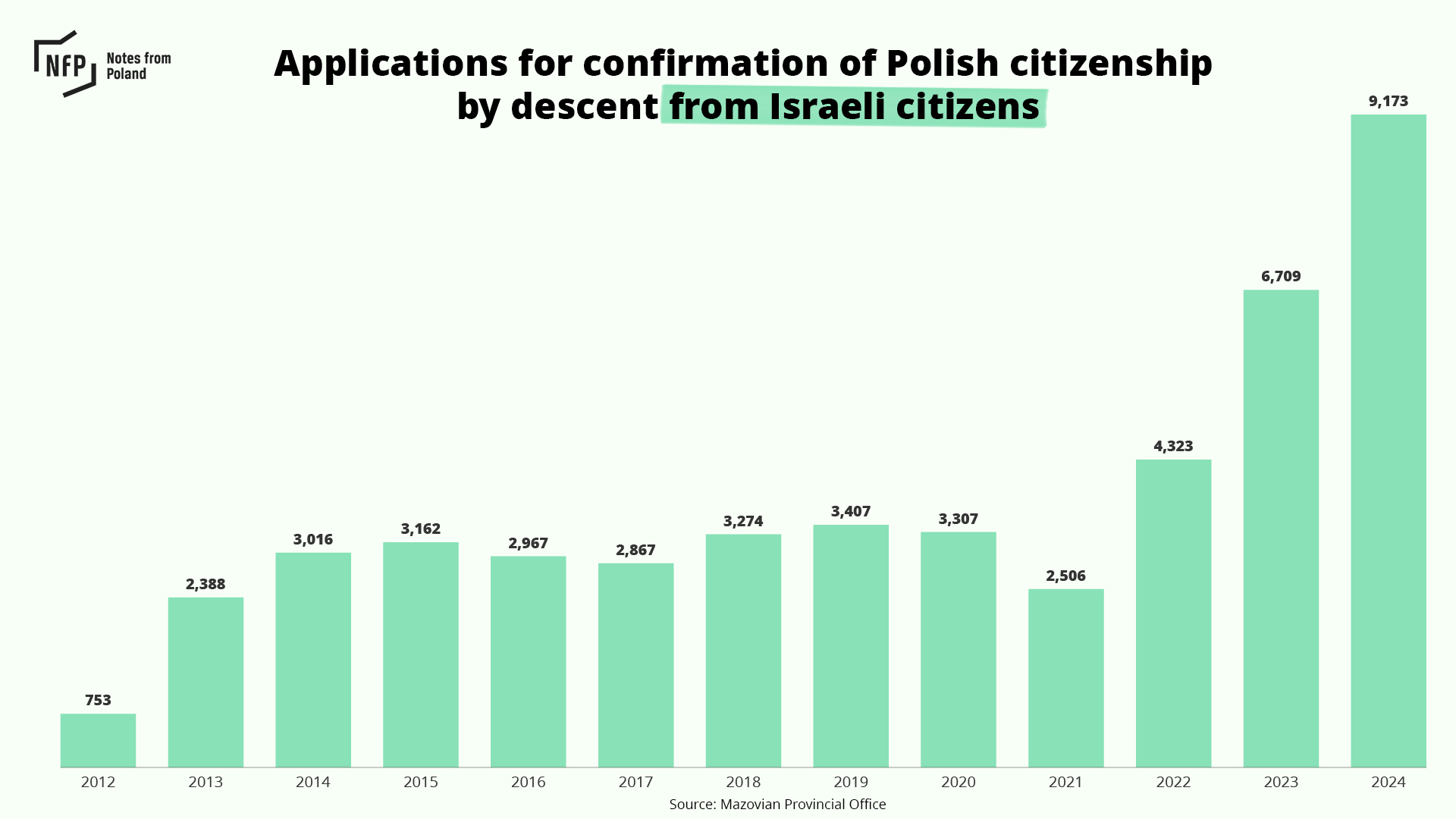

The number of Israelis applying for Polish citizenship by descent has surged in recent years, rising from around 2,500 in 2021 to over 9,000 in 2024.

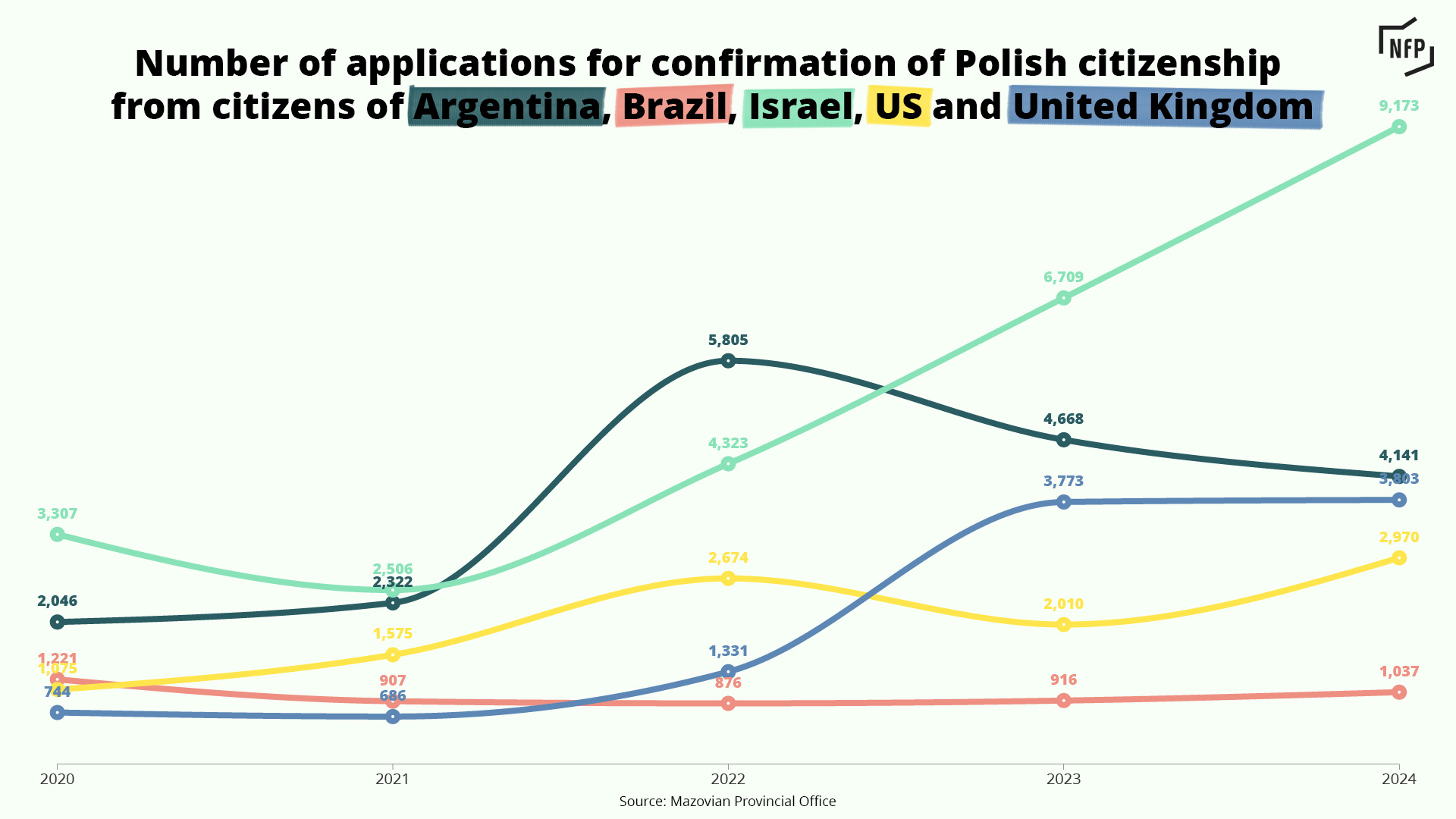

Data show that applications from the descendants of Polish emigrants in other countries – such as Argentina and the United Kingdom – have also risen, but Israelis make up the largest group.

Under Polish law, people who had a Polish parent, grandparent or great-grandparent who was born in or lived in Poland after January 1920 and was never stripped of their Polish citizenship are themselves regarded as holding Polish citizenship.

Such individuals do not therefore technically apply to receive citizenship; they request confirmation of their existing citizenship. Such requests for people currently residing outside of Poland are processed by the administrative offices of Mazovia, the province where the Polish capital of Warsaw is located.

It received 24,845 applications overall last year, up from 11,000 in 2020. The high volume of applications has created challenges for officials, extending waiting times to up to 18 months.

The largest number of such applications come from Israel, where many people have roots in Poland, which was once home to the world’s largest Jewish community.

The majority of the 3.5 million Jews who lived in Poland before World War Two were murdered during the German-Nazi occupation. However, among those who emigrated or fled before, during and after the war, many ended up in what is now Israel.

Between 2013 and 2021, the number of applications for confirmation of Polish citizenship submitted by Israelis was stable, remaining in the range of approximately 2,300-3,400 applications per year, data from the Mazovian Provincial Office sent to Notes from Poland show.

However, after 2021, when there were 2,506 applications, the number began to increase rapidly: to 4,323 in 2022; 6,709 in 2023; and 9,173 in 2024.

Applicants are not required to visit Poland in person. Specialised law firms often handle cases remotely. Successful applicants must supply ancestral documents, such as old Polish passports, birth certificates or marriage records.

Piotr Cybula, a Polish lawyer who specialises in citizenship confirmation cases, links the surge in Israeli applications to security concerns, particularly after the Hamas attacks on 7 October 2023.

While the European Union offers visa-free travel to Israeli citizens, holding a passport from an EU country such as Poland simplifies access to long-term residence or work permits.

“They often say they want to work or study here, but in the back of their minds, it’s about security,” Cybula told the Gazeta Wyborcza daily last month.

It is "impossible to imagine modern Israel or modern Judaism without our Polish roots", says Israeli ambassador @YacovLivne

He called on Poles and Jews to remember that, as well as the “dark chapter” of the Holocaust, they have centuries of shared history https://t.co/5GeGspQJp6

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 20, 2023

However, some applicants face hurdles. Polish legislation in force from 1920 to 1951 revoked citizenship from those who served foreign countries as public officials or in militaries.

“[Even] a teacher or a bank employee were treated as public servants, so this is not a small group at all,” says Cybula.

That law still affects individuals with ancestors who held such roles, including some who served in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF). Applicants must now provide IDF-issued certificates confirming non-service to avoid disqualification, says Cybula.

Others who have faced problems obtaining Polish citizenship due to the 1920-51 law have taken their cases to court, adds the lawyer.

Hollywood star Jesse Eisenberg, whose ancestors were Jews from Poland, has applied for Polish citizenship.

He says he feels a strong connection with the country – where his upcoming movie was filmed – and wants to help improve Polish-Jewish relations https://t.co/kdtrzFybrR

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) May 23, 2024

Interest in Polish passports is not limited to Israel. Piotr Stączek, another lawyer, told Gazeta Wyborcza that he sees a rise in South Americans seeking employment opportunities in Poland. Data from the Masovian Provincial Office shows a rise in applications from Argentina in recent years.

There has also been a rise in applications from the UK, with Stączek noting that this is above all linked to Brexit, which saw British people lose the rights they had previously held as EU citizens.

Cybula notes, however, that relatively few among the thousands who are applying each year to confirm Polish citizenship actually plan to relocate to Poland.

“Almost none of them want to live here,” said Cybula. “For many, it’s about having the option available if circumstances change.”

A centre for the study of Polish culture has opened in Brazil as part of a collaboration between universities in the respective countries.

It will also act as a focal point for research on the large Polish diaspora in Brazil and the rest of Latin America https://t.co/GpHfB1yoPF

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 19, 2024

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: cottonbro studio / Pexels

Alicja Ptak is deputy editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland and a multimedia journalist. She has written for Clean Energy Wire and The Times, and she hosts her own podcast, The Warsaw Wire, on Poland’s economy and energy sector. She previously worked for Reuters.