By Mateusz Bartel

Although it was the Olympics that dominated the Polish sporting news this summer, the success of a Polish chess player did not escape public attention. Jan-Krzysztof Duda’s victory at the Chess World Cup in Sochi, Russia, was the greatest achievement in Polish chess that most followers of the game can remember.

As Garry Kasparov, one of the most outstanding grandmasters in history, noted, Duda was following in the footsteps of such greats as Akiba Rubinstein and Miguel (Mieczysław) Najdorf, major figures in a golden age for Polish chess that was cut short by tragic events in their country and the world.

Duda beat Sergey Karjakin, the record semi-finalist in the history of the World Cup, in the Final 1.5-0.5, thanks to a convincing win in game 2, and became the first Polish player to win the #FIDEWorldCup. pic.twitter.com/IDUWoANaWj

— International Chess Federation (@FIDE_chess) August 5, 2021

From powerhouse to void

Rubinstein was for many years one of the world’s top players. In 1910-1914, he was regarded as the best there was, but was denied a shot at becoming world champion by financial concerns. At the time, it was the challenger who had to put up the funds for the winnings. The sum was determined by the defending champion, who was thus able to avoid playing an inconvenient rival.

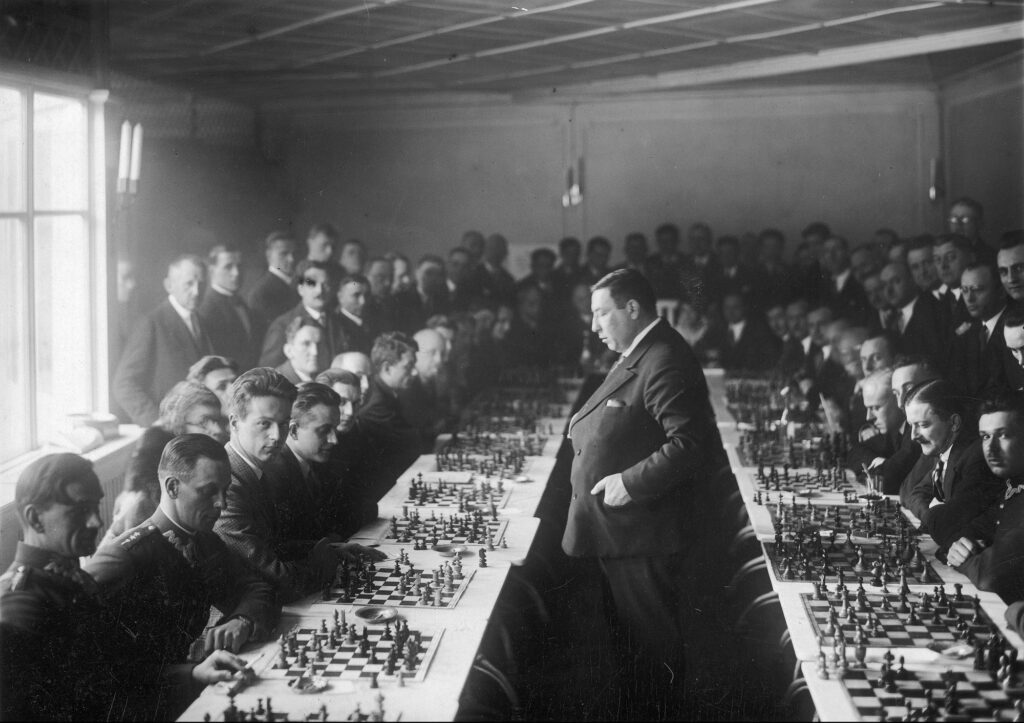

Apart from his individual successes, Rubinstein also led Poland to the gold medal at the 3rd Chess Olympiad in Hamburg in 1930. Notably, he was one of four of the five Polish players at the event with Jewish origin.

Akiba Rubinstein playing 25 games simultaneously, Poznań, 1931 (photo: szukajwarchiwach/public domain)

The Hamburg tournament was one of the country’s many international successes – between 1928 and 1939 Poland was almost an ever-present on the podium at tournaments. With powerful state patrons, such as Poland’s head of state and renowned chess lover, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, came generous funding for the game.

The Second World War changed the fortunes of Polish chess. After 1939 the world’s top players were at the Olympiad in Buenos Aires, where Poland came second. Most of them, however, including Najdorf, did not return home and began to represent other countries. Since then, Poland has not had players of the same calibre and never again won medals in the men’s tournament.

The void left by so many outstanding masters – many of them Jewish – who either emigrated or died proved impossible to fill. One might expect the realities of communist-era Poland to have provided good conditions for ushering in a return of the golden age of chess. The game was treated very well throughout the Eastern bloc, even becoming the national sport in the Soviet Union.

Ksawery Tartakower, Paulin Frydman and Mieczysław Najdorf compete for Poland against Argentina, Warsaw, 1935 (photo: szukajwarchiwach/public domain)

Just why chess in Poland did not develop as it did in neighbouring countries remains unclear.

Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and even East Germany hosted top tournaments, fostered homegrown masters and a rich chess culture, while Poland always trailed behind. Throughout the entire communist era, only two Polish players became grandmasters.

The best Polish chess player of the period, Włodzimierz Schmidt, in his heyday was ranked towards the bottom of the top 100 in the world. At the time, though, there was much less competition than now, as players from China and India had not yet become a force.

The Polish opening

Somewhat unexpectedly, Polish chess took a turn for the better after the changes of 1989. Activists and organisers appeared in Poland, and tournaments in the country were often the first stop for rising-star players from beyond the country’s eastern border as they headed west.

This gave a new generation of Polish players a chance to develop, and from the early 1990s the number of grandmasters began to grow. The annual Rubinstein Memorial in Polanica-Zdrój, established in 1963, became one of the most prominent tournaments in the world in the late 1990s, and Polonia Warsaw, sponsored by Polkomtel, held world-class tournaments.

A big boost came from the naturalisation of Russian grandmaster Michał (Mikhail) Krasenkow, who began to represent Poland in the mid-1990s. Ranked 10th in the world in 2000, he became an authority to young players. Among them was Bartłomiej Macieja, who in the same year reached the last 16 in the World Chess Championship.

Today on world chess day, 15 year old chess prodigy Young Indian Grandmaster R Praggnanandhaain beat 57 year old Michael Krasenkow 2:0 in two game tie break. Prag advanced to 4th round with the win ❤

Battle of ages, a treat for chess fans.❤

Chess is beyond age. Amazing game.. pic.twitter.com/ZIZxWuJXGM

— Amit Gadre (@Longterm_wealth) July 20, 2021

Many Polish women left their male counterparts in the shade at this time, bringing home the bronze medal from the Olympiad in 2002, gold from the European team championships in 2005, and silver at the 2016 Olympiad.

Chess continued to grow in popularity in Poland as major tournaments were held. Out of the new generation of talented players, Radosław Wojtaszek emerged as the unquestioned leader.

Born in 1987, Wojtaszek was the first player born in Poland to receive an International Chess Federation ranking of 2700. Ranked between 10 and 30 in the world in the last decade, he also served world champion Viswanathan Anand as a second – an assistant helping with preparation. The experience he gained in this role also gave him insights that he used to help other top Polish players.

Among the beneficiaries was his heir to the throne of Polish chess, Jan-Krzysztof Duda.

A new hope

The 23-year-old Duda’s talent was evident from the start. The prodigy developed dynamically but also systematically, and by the age of 16 he was among Poland’s top players and was called up to the Chess Olympiad.

In Tromsø in 2014, Janek, as he is commonly known, was the best player in a team that fought for a high position until the final rounds. But this was not his first appearance at a top-level team competition. In 2013, he was also part of the “Poland Futures” team at the European team championship in Warsaw.

Four of the five players went on to represent their country at the Chess Olympiad in Batumi in 2018, when they caused a sensation, defeating chess powerhouses such as Russia, Ukraine and the United States before being unfortunate to take fourth place.

World chess champion Magnus Carlsen hadn’t been beaten for 125 games — or two years, two months and 10 days.

Then he played Jan-Krzysztof Duda in round five of the Norway Chess tournament. https://t.co/3w4KI3De4T

— CNN International (@cnni) October 12, 2020

Duda soon secured his place among the global chess elite. He broke the 2700 ranking points barrier in 2017, placing him around 40th in the world. By December 2019, he had progressed to 12th with a new highest points tally of 2758.

This consolidated the young Pole’s position on the verge of joining the world’s very best, but he still needed a spectacular tournament success. Although Duda made history in October 2020 by breaking Magnus Carlsen’s undefeated streak, this was just one match. That was to change in Sochi.

Duda’s endgame

In Russia, Duda played the tournament of his life. On the way, he had to defeat seven rivals. With each of them he played two classical time limit games, followed by a rapid tie break. Astonishingly, the Pole did not lose a single game, which had never happened before.

On his way, he beat the World Championship runner-up from 2016, Sergey Karjakin, in the final, as well as Magnus Carlsen, the world champion since 2013. He also became the first winner of the World Cup (held in this format since 2005) not born in the former Soviet Union.

Magnus Carlsen: "Huge congratulations to Duda for winning the World Cup. Considering the line of opponents he beat in the last four rounds, never losing a game and therefore never being in a must-win or desperate situation, it's a massive achievement."

📺 https://t.co/UOpIeE57qw pic.twitter.com/n8Bdrhnz0w

— International Chess Federation (@FIDE_chess) August 5, 2021

Duda is also an immensely likable player for chess afficionados. His creative and uncompromising playing style, combined with self-assurance, often produces an explosive mix that is as threatening to his opponents as it is attractive to spectators.

I have witnessed all Janek’s attributes first-hand. We first faced each other in 2013, when I was still the strong favourite. I was 28 years old and one of the top Polish chess players, while my opponent was a 15-year-old promising junior. To my surprise, he gave me no respect, aiming for the top prize from the first move, and only my greater experience allowed me to salvage a draw.

The scale of Duda’s genius became clear to me at a training camp in 2017. In our eight or so practice games, I could not even manage a single draw. Despite the friendly nature, he played with the absolute commitment that characterises the greatest grandmasters.

The Pole’s recent success comes at a promising time for chess in the country. Recently, the Polish Chess Federation gained an influential patron in Łukasz Schreiber, a secretary of state in the prime minister’s chancellery and a former talented junior chess player who even won a gold medal in his age group at the 1997 Polish championship.

czegoś podobnego nie pamiętam, aby urzędujący minister komentował zawody sportowe! Na kanale Polskiego Związku Szachowego na YT minister Łukasz Schreiber komentuje rozgrywki na mistrzostwach Polski w szachach (sam kiedyś był zawodnikiem) @LukaszSchreiber @PZSzach #szachy pic.twitter.com/7F8czS4TI9

— Dariusz Ciepiela (@Ciepiela_Darek) May 7, 2021

Thanks to Schreiber’s efforts in finding sponsors for chess among state-owned companies, prize money at the Polish championship has increased considerably and a new Polish Cup has been established.

For now, though, it is Jan-Krzysztof Duda’s future that is the main point of interest. His triumph in the World Cup, the third most important FIDE tournament, gives him an entry to the 2022 Candidates Tournament.

The winner of the eight players will earn the right to pit his wits against the world champion (the victor of this year’s match between Carlsen and Ian Nepomniachtchi). If Duda managed that, he would even trump the achievements of the legendary Rubinstein.

Translated by Ben Koschalka

Main image credit: Anna Lewanska / Agencja Gazeta