Although the cash-for-visas scandal knocked Poland’s ruling right-wing party off its stride, it also helped to ensure that migration remained a key issue in the closing stages of Poland’s parliamentary election campaign.

The governing party has tried to refocus debate onto the EU “migration pact”, where the opposition remains vulnerable, and in such a closely fought electoral contest the issue could be critical to the outcome.

Mobilisation is the key

Poland’s parliamentary election, scheduled for 15 October, is extremely closely fought and evenly balanced.

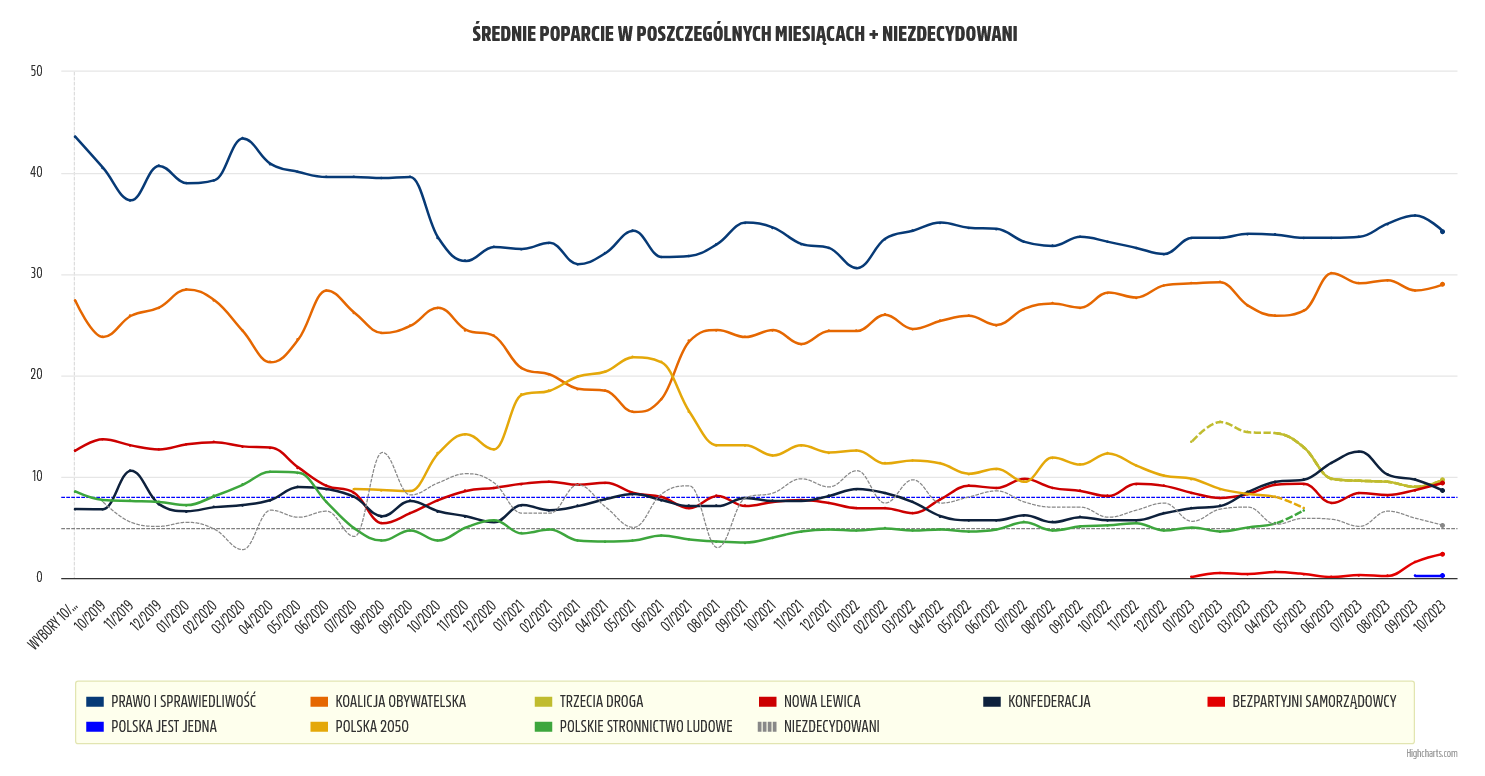

Opinion polls suggest that the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS), Poland’s governing party since autumn 2015, will emerge as the largest grouping but is likely to fall short of an overall majority. It is currently averaging 36% support but needs around 40% to have a good chance of securing an unprecedented third term in office.

Monthly average support in polls for the main groups contesting Poland’s parliamentary elections (source: ewybory.eu)

Somewhat surprisingly, given that the campaign was widely expected to be dominated by socioeconomic issues, migration has emerged as one of the dominant campaign themes.

Given the extremely divided political scene, there is very little evidence of any significant transfers of voter support between the governing and opposition camps. The election outcome will depend largely upon which of the two sides can mobilise their supporters to turn out and vote, and a relatively small number of voters could play a decisive role in determining the result.

Most of the voters that PiS lost since its 2019 election victory have not switched to the opposition parties and currently intend to abstain, so the key to the party’s success will be persuading these disillusioned electors to return to the fold. It has spent much of the campaign trying to find ways to win back these voters.

Poland’s president and PM have condemned the EU’s migration pact, which was approved by member states yesterday.

"Why should we agree to this diktat from Brussels and Berlin?” asked @MorawieckiM, who pledged to defend "Polish borders and sovereignty" https://t.co/Cb2JKtaFis

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 5, 2023

An emotive issue

An important element of PiS’s campaign strategy has been to call multiple referendums on the same day as the parliamentary poll.

These include questions designed specifically to remind voters about various unpopular policies and stances associated with the liberal-centrist Civic Platform (PO), Poland’s governing party between 2007-15 and currently the main opposition grouping.

Two of the four referendum questions are on migration issues, asking Poles if they oppose: the removal of a large fence erected last year along the Polish-Belarussian border to prevent the inflow of illegal migrants from the Middle East and Africa; and the EU’s latest proposals for dealing with migrants and asylum seekers.

The ruling party wants to make this year's election a referendum on opposition leader @donaldtusk.

While old foes Kaczyński and Tusk are relishing their renewed battle, it may benefit neither and instead further fuel the recent rise of the far right https://t.co/CTdwyPVkKu

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) August 16, 2023

The vast majority of Poles oppose the EU “migration pact”, which will require member states that are less vulnerable to “irregular” migrants crossing their border to either take in a minimum relocation quota or make “solidarity” payments of €22,000 per migrant not accepted.

The referendum questions are also meant to tie in with, and highlight, PiS’s overarching campaign themes of security and national sovereignty, and specifically to revive an issue around which it mobilised successfully in the run-up to the 2015 parliamentary election held at the peak of that year’s European migration crisis.

Then, PiS, at the time the main opposition party, lambasted the PO-led government for agreeing to admit 6,200 migrants as part of a similar EU-wide scheme for the compulsory relocation of mainly Muslim migrants from the Middle East and North Africa.

PiS viewed the scheme as part of a wider clash of cultures, arguing that its political and symbolic importance went well beyond the numbers involved and that it threatened the country’s sovereignty, national identity and security.

PiS has continued to argue that allowing mass immigration from Muslim-majority countries threatens Poland’s status as one of Europe’s safest countries. It accused PO leader Donald Tusk – who was prime minister from 2007-14 and then returned to Polish politics in 2021 following a stint as European Council president – of being one of those responsible for the EU’s loose migration policies.

Migration is an emotive topic that always has the potential to become electorally salient, particularly if linked to broader national security concerns. So PiS saw putting the issue at the heart of its reelection campaign as a key means of mobilising its core supporters and persuading its disillusioned former voters to return to the fold.

Turning the tables on PiS

Knowing that migration was a very difficult issue for the opposition, PO tried to turn the tables on PiS. It argued that the Belarussian border fence was ineffective, and highlighted what it said was the dissonance between the ruling party’s rhetoric on this issue and the fact that it had overseen Poland’s largest-ever wave of immigration, including many more foreign workers from outside Europe than the EU was planning to transfer.

Poland's election in charts.

Amid low unemployment, Poland has been admitting record numbers of immigrants.

It has issued more residence permits to non-EU citizens than any other member state in recent years.

For these charts and more, see our report: https://t.co/SPjjRAFnu5 pic.twitter.com/cnJHDxzy8w

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 11, 2023

The objective here was to create doubts among wavering former PiS supporters – who were disillusioned with the party but may have considered returning to the fold if they felt that the current opposition would end up accepting the EU’s plans if elected to office – that the ruling party really was as effective at controlling immigration as it claimed to be.

Indeed, at one point it appeared that PiS’s plan to make migration a key election issue could backfire. Media reports suggested that the government was embroiled in a damaging fraud scandal involving Polish consular officials in developing countries processing work visa applications at an accelerated pace and without proper checks through intermediary companies in exchange for bribes.

At the end of August, Piotr Wawrzyk, the deputy foreign minister responsible for consular affairs, was suddenly dismissed on the same day that Poland’s Central Anticorruption Bureau (CBA) carried out a search of the ministry, and then dropped as a PiS election candidate.

The opposition has accused the government of presenting itself as being anti-immigration while in fact overseeing a corrupt system that issued visas to 250,000 Asian and African migrants, and which led a deputy foreign minister to be sacked last week https://t.co/tKBjMBPtHe

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 8, 2023

Then, in September the scandal escalated when prosecutors announced that corruption charges had been brought against seven individuals, with three being detained, over their suspected involvement in alleged visa fraud.

This allowed PO and the opposition to argue that, while the government presented itself as being opposed to uncontrolled illegal immigration, it was actually overseeing a corruption-prone system in which hundreds of thousands of work visas could have been allocated in a fraudulent way, including to those who might pose a national security risk. Tusk dubbed it the “biggest scandal of the twenty-first century in Poland”.

Defusing the crisis

The visa scandal certainly knocked PiS off balance, causing it to lose momentum at a critical point in the campaign. By appearing to show that the system for controlling permits for foreign workers coming to Poland was illusory and corrupt, the scandal opened up the party to charges of inconsistency and hypocrisy, undermining PiS’s core campaign message that it was the only effective guarantor of secure Polish borders.

It meant that the party had to exert energy on crisis management at a point when, following the success of its multiple referendums initiative, it was developing some real momentum for the first time in the campaign. It may also have planted some doubts among wavering PiS voters as to whether the ruling party’s opposition to mass Muslim immigration was more rhetorical than real.

Poland has criticised @Bundeskanzler Olaf Scholz for his comments on an ongoing scandal over corruption in the Polish visa system.

Government figures accused him of seeking to "interfere in the campaign" for next month's elections https://t.co/y22zN7Ttez

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 25, 2023

However, although the scandal may have fired up government opponents, it left PiS voters and “undecideds” distinctly unmoved and did not deliver the knockout blow that many opposition politicians hoped for.

Moreover, PiS tried to defuse the crisis by suggesting that some of the problems identified dated back to the opposition’s time in power, and pointing out that the investigation only involved several hundred visa applications, not the hundreds of thousands claimed by the opposition, all of which were vetted with no security threats identified, and the majority in any case rejected.

The party also insisted that it was the Polish state that had uncovered the scandal and took swift and decisive action against the suspected or implicated individuals.

More broadly, PiS argued that the government had brought migrant workers into Poland to fill specific labour market gaps, and that there was a clear difference between allowing verified migrants to enter the country in a legal and controlled way, and EU-imposed quotas of illegal, unverified migrants.

A “container town” that will house up to 6,000 foreign workers – mainly from Asia – has been set up at the site of a chemicals plant being built by Polish state energy firm Orlen.

The facility features canteens, a police station, and even a cricket pitch https://t.co/QLW79SMCSz

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) June 20, 2023

Keeping migration a top campaign issue

A series of further developments kept the migration issue at the top of the political agenda.

Both the European Commission and Parliament sought clarifications on the cash-for-visas scandal, as did the German government which also introduced additional checks on its border with Poland to curb the flow of thousands of “irregular” migrants passing along smuggling routes through these two countries.

For its part, the Polish government introduced controls on the Slovak border, and reiterated its opposition to the Union’s migration pact by rejecting a joint statement on the issue at the October EU leaders’ summit.

Poland introduced controls on its border with Slovakia today and closed some crossing points completely as part of measures to restrict the entry of irregular migrants.

It has also deployed the military to support the new border restrictions https://t.co/0Bhfa46NXU

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 4, 2023

In fact, in spite of the reputational damage that PiS may have suffered from the scandal, the party felt that ultimately it benefited from migration remaining a top campaign issue. It meant that the opposition was not focusing on other questions where the government was much more vulnerable, such as economic insecurity and the cost of living.

Indeed, rather than highlighting the government’s hypocrisy on the migration issue as the opposition intended, PO’s attacks may have simply legitimised PiS’s narrative that uncontrolled mass migration from predominantly Muslim countries undermined Polish security.

The continued salience of the migration issue also allowed PiS to refocus debate back on to the EU “migration pact”, where its stance was much more credible and coherent than the opposition’s, who it accused of only pretending to be against illegal immigration for electoral purposes.

For its part, the opposition accused PiS of misrepresenting the pact, arguing that it included exemptions for countries under migratory pressure such as Poland, which has welcomed millions of refugees from Ukraine following the Russian invasion.

However, PiS pointed out that during the 2015 migration crisis, PO was willing to accept EU compulsory relocation quotas, and that as European Council President, Tusk threatened the Polish government with sanctions for opposing the scheme.

It argued that exemptions from the new migration pact would be at the whim of the European Commission which, it said, was not a trustworthy partner and often applied politically motivated double standards.

More broadly, PiS argued that PO was unreliable on the migration issue, citing examples of prominent party figures who had interfered with the work of patrols on the Polish-Belarussian border.

Berlin and Brussels’ interventions also played into PiS’s narrative that foreign powers were trying to interfere in the election, and the party’s attacks on Tusk whom it accused of working for Germany to undermine Polish interests.

Finally, the release of Green Border, a film by Polish director Agnieszka Holland who is closely associated with the opposition, and which PiS presented as a defamatory attack on Polish guards on the border with Belarus, also allowed the ruling party to portray itself as the only credible defender of national security.

Poland’s government will show a “special clip” in cinemas before screenings of Green Border – a new Agnieszka Holland film depicting mistreatment of refugees – to inform viewers of the “many untruths” it contains https://t.co/1RNGi2qhnJ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) September 21, 2023

Critical in a closely fought contest?

Ultimately, the election is likely to be determined by whether the strongest driver of voting intentions ends up being dissatisfaction with PiS’s record in government or wariness of handing the reins of power back to Tusk and PO, together with the performance of the minor parties.

Nonetheless, as a highly emotive issue, migration has, somewhat unexpectedly, come to play a key role in the closing stages of the campaign.

Although the visa scandal made it something of a double-edged sword for PiS, it also allowed the ruling party to turn the focus back onto the EU “migration pact” where the opposition remained extremely vulnerable.

This could be critical in such a closely fought electoral contest, where the key to victory will be which of the two sides can mobilise their supporters most effectively.

Sunday's elections are above all a clash between two parties, PiS and PO, that have ruled Poland for the last 18 years

We have prepared 21 charts showing Poland’s economic, social and democratic progress over that time.

Click here to see them all 👇https://t.co/rA5nIT8pv7

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 9, 2023

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Daniel Gnap/KPRM (under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 PL)