By Daniel Tilles

Poland’s proposed law deserves to be criticised, but the country is not the only one that should be asking itself questions about its actions during the Holocaust. The United States and Britain have largely ignored this shameful episode in their own histories.

The last few days have seen a bitter dispute over the Polish government’s decision to push ahead with a law that would criminalise those who falsely assign the Polish nation or state responsibility for the crimes of the German Third Reich.

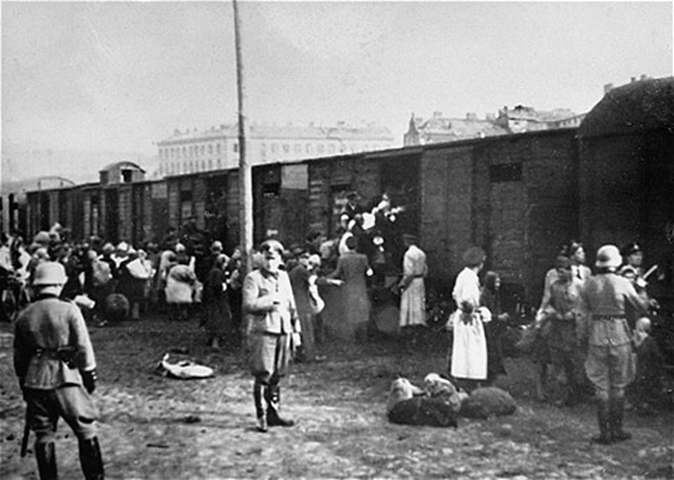

Debate has focused on the use of the phrase “Polish death camps”, a factually inaccurate but also deeply offensive term that I have consistently argued against the use of, given that Poles were, after Jews, numerically the greatest victims of the German Nazi camps. More broadly, Poles justifiably feel that their experience of and actions during the war are little recognised, and sometimes misrepresented, outside their own country.

Yet one can have little sympathy for the Polish government in this latest episode, both with regard to the proposed law itself and the manner in which it has been handled. The way to tackle historical ignorance is through education, publicity and diplomacy, not threatening jail terms for those who make factual errors. Such aggressive measures do little to draw attention to Polish suffering and heroism during the war, and instead simply raise suspicion that Poles have something to hide.

Moreover, voting the bill through parliament the day before International Holocaust Remembrance Day was a particularly crass move, bound to provoke controversy and condemnation. As we have seen since then, a law that is supposed to defend Poland’s good name abroad and to challenge the stereotype of Poles as antisemites has done precisely the opposite. It has resulted in a wave of negative publicity in international media, which has in turn brought out nasty, antisemitic views from some Poles online and in the media, including on state-run TV.

The international response also left much to be desired. While Israeli anger is understandable, many politicians and commentators have offered exaggerated, sometimes outright false claims regarding Polish actions against Jews during the war. Criticism of the proposed law has also been undermined by misrepresentation of it, in particular ignoring the fact that it criminalises only false claims of Polish responsibility for German crimes (rather than any statement of Polish involvement in crimes against Jews) and that it specifically exempts academic work. Such sloppiness simply gives the Polish government an excuse to ignore legitimate concerns.

And indeed the bill is extremely problematic. Who will decide what is “true” or “false”? What counts as academic work? These concerns are amplified by the government’s broader, revisionist “historical policy”, which seeks to whitewash the negative aspects of Poland’s past, and by its politicisation of the judiciary, prosecutors’ offices and Institute of National Remembrance, the three institutions that will be responsible for implementing the new law. Undoubtedly it will have a chilling effect on discussion and education about important parts of Polish history.

Active and passive accomplices

Taking a step back, however, there is also a broader point to be made, which is that, while there were numerous incidents during the war in which a minority of Poles blackmailed, betrayed or butchered Jews, they are hardly unique. Other countries, in their own way and under different circumstances, have their own inglorious histories to confront as well.

Many, of course, produced collaborationist governments, which, with a greater or lesser degree of willingness, participated in the Nazis’ Holocaust machinery. Poland, by contrast, never produced a puppet regime or any significant collaborationist group. Britain and America were never occupied by the Germans, meaning that they did not directly participate in the Holocaust. Yet their passivity and callousness may indirectly have caused more Jewish lives to be lost than the number killed by Poles (though of course exact figures are impossible to calculate).

This began even before the war, when in May 1939 the St Louis, a ship carrying almost 1,000 Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi persecution, was turned away by first the US and then Canadian governments. Forced to return to Europe, hundreds of those on board would go on to die in the Holocaust. The American government’s decision was a reflection of public sentiment: a few months earlier, when asked by Gallup if their country should accept 10,000 mostly Jewish child refugees from Germany, 61% said no and only 30% yes.

In 1942, after the Holocaust had begun, another ship, the Struma, carrying hundreds of Jews who had managed to escape Nazi-controlled Europe and were hoping to reach the British Mandate of Palestine, was turned away by the British authorities. After being sent back to sea without a working engine, it sank, killing almost 800 Jews on board.

These are just two incidents, but they fit a general pattern. As numerous historians have documented, despite being well aware of the Nazis’ mass murder of the Jews from the very start of the Holocaust in 1941, the British and American authorities were extremely reluctant to take any action to help them. The excuse at the time was that all attention and resources had to be focused on winning the war, which in turn was the best way to help the Jews. Yet there were numerous opportunities to provide assistance or refuge that would not have detracted from the war effort. (For example, during the war US State Department obstruction meant that only 10% of visa quotas for Europeans were filled; ships carrying troops and equipment often returned across the Atlantic empty.)

Western antisemitism

In reality, the primary reason for the lack of help was anti-Semitism. Prejudice among the ruling classes was rife on both sides of the Atlantic. Towards the end of the war, the US Treasury Department wrote a damning report, entitled “The Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews”, which concluded that there had been “wilful attempts to prevent action from being taken to rescue Jews”. The Secretary of the Treasury had no doubt that these failings were, at least in part, motivated by hostility towards Jews, telling the assistant secretary of state that he was “particularly anti-Semitic” and describing the assistant secretary of war as an “oppressor of the Jews”.

Even among politicians who did not harbour such sentiment, there was a fear that making visible effort to help Jews, and in particular accepting refugees, would exacerbate anti-Semitism among the public and could strengthen claims (particularly in the US) that the Allies were fighting a “Jewish war”. Polling found that anti-Jewish feeling among the American public actually increased during the war. A State Department official warned that giving too much help to Jews would “to lend colour to the charges…that we are fighting this war on account of and at the instigation of our Jewish citizens”. In 1944, Britain’s Home Secretary deemed it “essential that we should do nothing at all which involves the risk that the further reception of refugees might be the ultimate outcome”.

We can never know how many Jews might have been saved had the Allies been more receptive. And of course they were not directly responsible for the deaths that they failed to prevent. Yet, equally, one can point to the fact that during the war Poles were living under a brutal occupation, in which life was often a struggle for survival. That does not excuse any action that some took against Jews, but it does help to contextualise and explain it. Moreover, while, for a British or American official, saving hundreds of Jewish lives could often mean simply allowing a ship to dock, and perhaps facing some anger from voters, in occupied Poland saving a single Jewish life could result in the execution of one’s entire family (as happened, in one of many tragic examples, to the Ulmas).

It is also worth noting that much of the Allies’ knowledge of the Holocaust, and many of the appeals for them to help the Jews, came from Poles: information was gathered by underground operatives, smuggled out of occupied Europe, then passed on via the Polish government-in-exile. The most famous messenger was Jan Karski, the underground courier who brought news of the Holocaust directly to the Allies, warning that “the Jewish people of Poland will cease to exist” unless action was taken. Yet in response, he was told by Anthony Eden that Britain had already accepted enough refugees and could not accommodate any more, while President Roosevelt simply said, “tell your nation we shall win the war”. Polish operatives, such as Witold Pilecki, who voluntarily had himself interned at Auschwitz in order to gather intelligence, also provided the Allies with detailed reports of the Nazi extermination camps. (For more, see Michael Fleming’s Auschwitz, the Allies and Censorship of the Holocaust.)

Reflecting on the past

Poles are often told by outsiders that they have not done enough to acknowledge and confront their Holocaust history. Whatever the truth in that, countries like Britain and the US have done even less. Most of the public have no knowledge of their countries’ responses to the Holocaust, which have been subject to little of the type of debate that has been vigorously pursued in Poland over the last couple of decades. While almost every Pole will be aware of – and most will have an opinion on – the Jedwabne pogrom, in which 340 Jews were killed, virtually no one in Britain will have heard of the Struma and the 800 Jews who died on board.

In making these arguments, I do not wish to claim that such incidents, or the actions that caused them, are comparable. And I certainly do not want to add to the atmosphere of “competitive victimhood” that we’ve unfortunately seen so much of in recent days. Indeed, one of the tragedies of this whole affair is that, amidst the undignified squabbling, the most important aspects of Holocaust Remembrance Day have been lost: the respect that should be paid to the victims, and the opportunity that should be taken to reflect on how such a tragedy could have occurred (in the hope of ensuring that it never does again).

With regard to the latter, it is important to consider not just the actions of the German Nazis and their collaborators, who carry the responsibility for the genocide, but also those of the bystanders, who looked on as the tragedy unfolded. This should be a time for self-reflection, for nations to question this episode of their own history, rather than pointing fingers at others.

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.