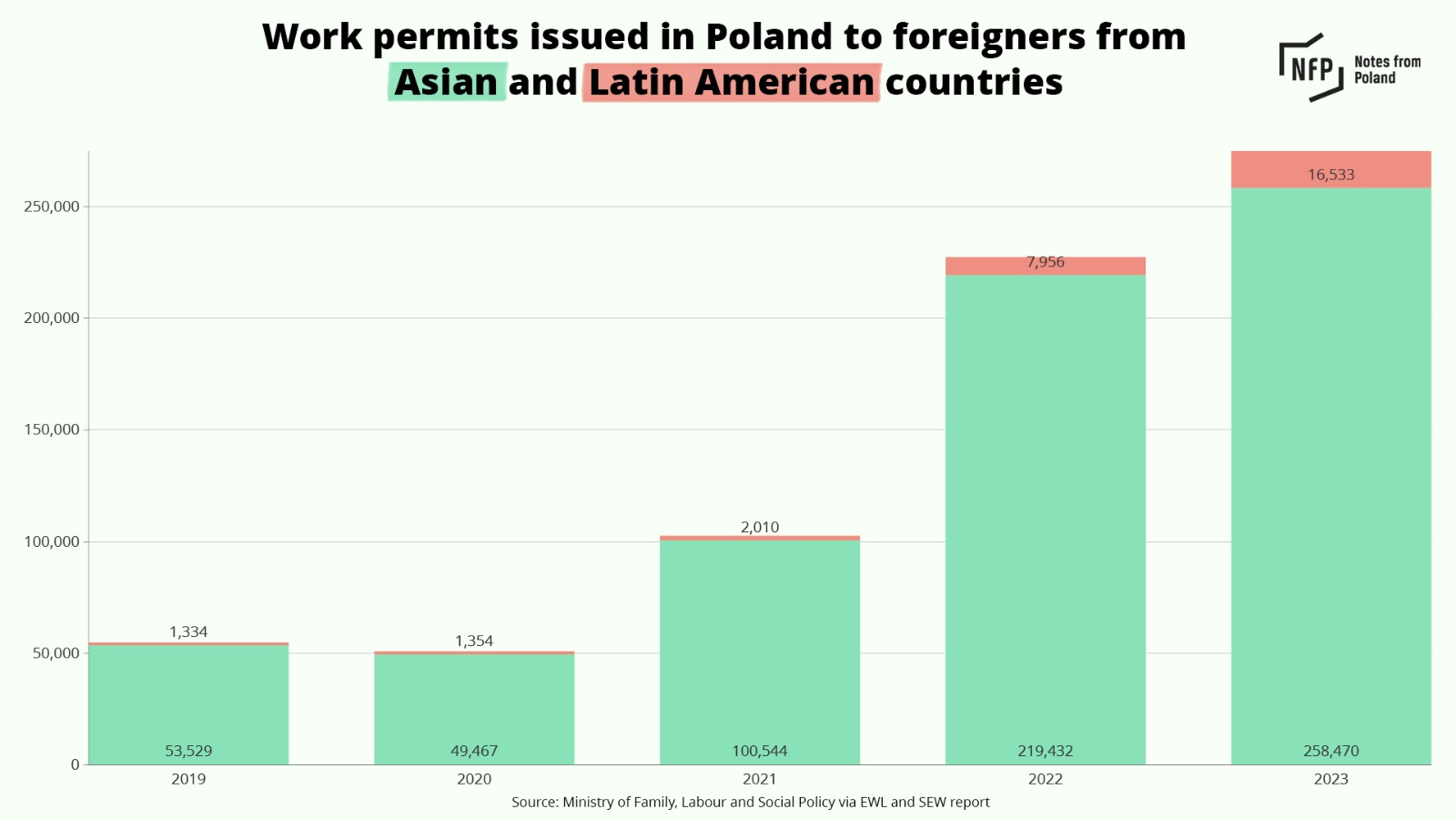

The number of work permits issued by Poland to migrants from Asia and Latin America has risen fivefold in the space of five years, reaching 275,000 in 2023. The figures have accelerated particularly fast since 2022, when most Ukrainian men were banned from moving abroad due to the war.

The new arrivals from Asia and Latin America are generally satisfied with their new lives in Poland, finds a new report based on interviews with hundreds of such immigrants.

“Poland, traditionally perceived as a country of emigration, is increasingly – to our surprise – becoming a country of immigration, a country that immigrants choose with confidence of security, stability and development,” said Jan Malicki, director of the University of Warsaw’s Centre for East European Studies (SEW).

The study, produced by SEW and EWL Group, an employment agency, notes that in 2019, Poland issued around 53,529 work permits to people from Asia and 1,334 to those from Latin America, making a total of 54,863.

By 2023, those numbers had increased to 258,470 work permits for Asians (a 383% increase), 16,533 for Latin Americans (a 1,139% increase), and a total of 275,003 (a 401% increase).

Those figures rose particularly fast from 2022 onwards, with EWL’s CEO, Andrzej Korkus, noting that the war in Ukraine has resulted in a decline in the number of workers coming to Poland from that country, leading Polish employers to look elsewhere.

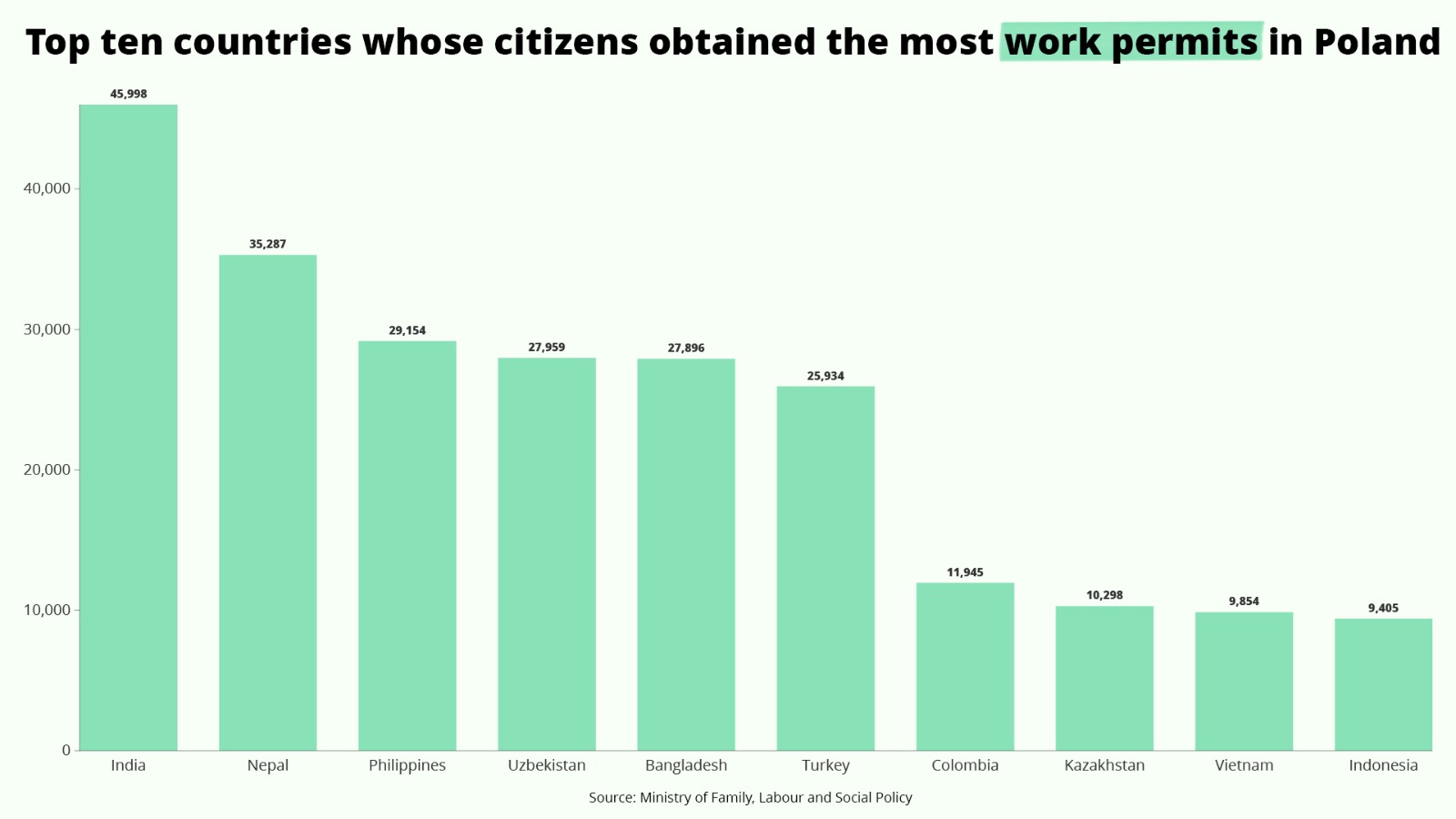

The report does not identify the nationalities of the recipients of those permits, but data from Poland’s labour ministry shows that in 2023 the highest numbers of work permits were issued to: Indians (45,998), Nepalis (35,287), Filipinos (29,154), Uzbeks (27,959), Bangladeshis (27,896), Turks (25,934) and Colombians (11,945).

As part of their research, SEW and EWL conducted interviews with 450 immigrants in Poland, 324 of them from 14 Asian countries and 126 from six Latin American ones.

It found that 75% were men, 51% were aged 26 to 35 years, and 56% were employed in physical labour, such as construction, production and logistics. It is precisely those kinds of sectors that suffered staffing shortages due to Ukraine banning military-age men from leaving the country during the war and many men choosing to return.

Among those surveyed, 42% said that they are currently taking Polish lessons while a further 43% said that they were going to study the language. Over half (52%) said they use Polish as a language of communication at work (80% use English, while 17% use Spanish and 6% Russian).

Poland needs two million new foreign workers over the next decade to counteract the ageing of its population, says the state social insurance agency.

It notes that recent years have seen mass immigration, with over a million foreign workers now registered https://t.co/LW5278uawm

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) July 12, 2023

Two thirds (67%) said they had never worked abroad before coming to Poland. Asked what had motivated them to come, the most common answers were “I heard there are many things making life easier for immigrants in Poland” (36%), “I have acquaintances in Poland” (36%) and “I saw that many people from my country work in Poland” (35%).

On average, the immigrants said they had invested $1,576 on coming to Poland – for example on travel and obtaining permits. That investment appeared to have paid off: their average net monthly earnings before coming to Poland were $275 while in Poland they are $948.

That figure does not account for cost of living. However, the interviewed immigrants said that on average they have $258 left per month after paying all expenses relating to their stay in Poland. Over half, 56%, said they send money back to their home country (an average of $255 per month).

The number of foreigners in Poland’s social insurance system rose 6% in 2023 to reach 1.13 million. Immigrants now make up almost 7% of all those in the system

The largest increases were recorded by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Indians, Colombians and Nepalis https://t.co/eA1QVo0ydH

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 27, 2024

A large majority, 78%, said the work they had taken up completely or largely corresponded to what they had been expecting and 60% said it was suitable for their level of qualifications.

Using a so-called Net Promoter Score (NPS), which shows how likely someone would be to recommend something on a scale of -100 to +100, the report found that the immigrants are very likely to recommend working in Poland to friends and family. For Asian immigrants, the NPS score was 72 and for Latin Americans 60.

Asked about their plans, only 13% of the immigrants said they wanted to stay in Poland permanently. The largest proportion, 34%, intended to stay for over two years, with 29% planning one to two years and 2% one year maximum.

When asked what their main concerns were about staying in Poland, the most common answer was “poor language skills” (50%) followed by “fear that Poland will be attacked by Russia” (26%).

Mass immigration has left Poland's public administration “unable to cope”, reports the state audit office.

It found that applications for residence permits take an average of one year to process, with one individual waiting over seven years for a decision https://t.co/lXLquxNneN

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) March 20, 2024

Notes from Poland is run by a small editorial team and published by an independent, non-profit foundation that is funded through donations from our readers. We cannot do what we do without your support.

Main image credit: Anna Lewanska / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

Daniel Tilles is editor-in-chief of Notes from Poland. He has written on Polish affairs for a wide range of publications, including Foreign Policy, POLITICO Europe, EUobserver and Dziennik Gazeta Prawna.